Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Elbhafen

Lithograph, 1907

Wassily Kandinsky, Orientalisches

Woodcut, 1911

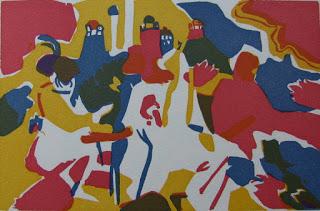

Wassily Kandinsky, Motif aus

improvisation 25: The Garden of Love

Woodcut, 1911

Oskar Kokoschka, Madchenbildnis

Lithograph, 1920

Lists of the major artists of German Expressionism usually include all the artists in the last paragraph except for Bleyl, with the addition of Franz Marc, Paul Klee, August Macke, Max Beckman, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Otto Mueller and Conrad Felixmüller. But as this post will show, there were many extraordinary talents working within Expressionism. German Expressionism was also unusually welcoming to female artists, such as Gabriele Münter, Marianne Werefkin, Jacoba van Heemskerck, Maria Uhden and Käthe Kollwitz.

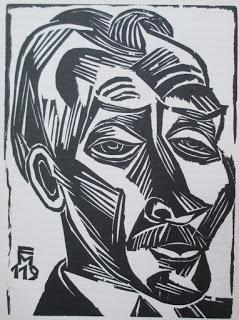

Conrad Felixmüller, Porträt Max John

Woodcut, 1919

Conrad Felixmüller, Mein Sohn Luca

Woodcut, 1919

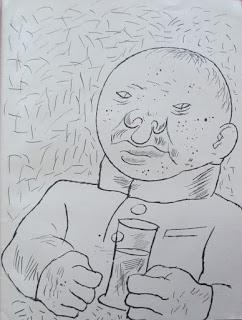

George Grosz, Thomas Rowlandson zum Andenken

Lithograph, 1921

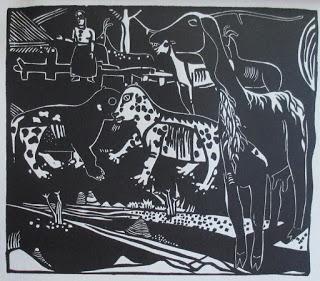

Heinrich Campendonk. Landschaft mit Ziegen und Wildkatzen

Woodcut, 1920

Ewald Mataré, Landschaft/Strasse

Woodcut, 1921

Eberhard Viegener, Simson im Temple

Woodcut, 1919

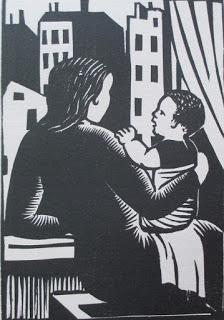

Georg Schrimpf, Mutter mit Kind

Woodcut, 1923

Maria Uhden, Frau am Wasser

Woodcut, 1918

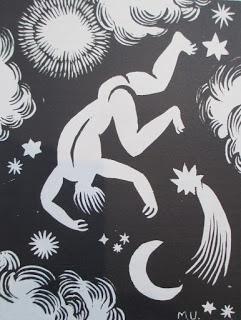

Maria Uhden, Himmel

Woodcut, 1917

Usually when a country experiences an intense flowering of radical art, there is resistance to what Robert Hughes called “the shock of the new”. In Germany, this resistance was so strong it led to the persecution of almost every artist allied to Expressionism. Under the Nazis, many were dismissed from their positions in fine art academies, banned from creating or exhibiting art, or from buying art materials, and the art museums of Germany were looted to systematically remove, and either destroy or sell, any Expressionist works. An official exhibition of Entartete Kunst, or Degenerate Art, was staged in Munich in 1937, to hold the Expressionists up to public ridicule. In the case of Erich Heckel, for instance, 700 of his works were removed from German museums, and his woodblocks and copperplates were destroyed.

Erich Heckel, Liegende (Frau)

Woodcut, 1913, revised with newly-cut red forms in 1924

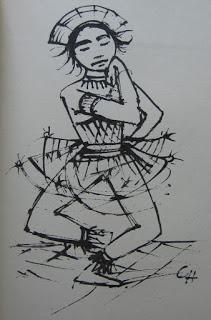

Karl Hofer, Tanzerin

Lithograph, 1921

Gerhard Marcks, Heimweg

Woodcut, 1923

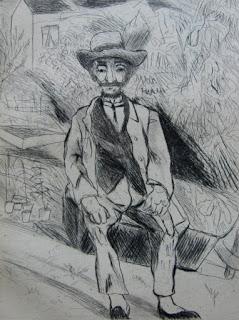

Rudolf Grossman, Der alter Gärtner

Etching, 1921

Rudolf Grossman, Der Kritiker

Lithograph, 1919

Otto Schubert, Frühling

Etching, 1920

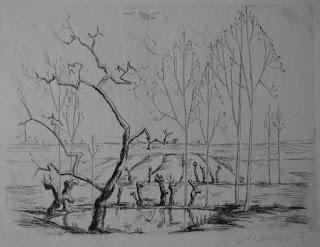

Felix Meseck, Landschaft

Etching, 1920s

It seems quite extraordinary now, but more than 16,500 works were removed from museums; many were destroyed, including some 4,000 paintings, drawings and prints burned in an auto-da-fé by the Berlin Fire Brigade in 1939. The most valuable were sold on the international art market through trusted dealers such as Hildebrand Gurlitt, the source of the treasure trove of 1,046 works found in the apartment of his son Cornelius Gurlitt in 2012, many of which have now passed to the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern. The name Gurlitt is entwined with the story of Expressionism and of Degenerate Art, for the Fritz Gurlitt gallery, run by Fritz’s son Wolfgang, and its associated publishing arm, the Gurlitt-Presse, was probably the most prominent promoter and publisher of Expressionist works. Wolfgang and Hildebrand Gurlitt were first cousins; both were suspect to the Nazis because of Jewish lineage and because of their association with Expressionism. Yet both profited from the exploitation of works seized either from museums or from Jewish owners by the Nazis.

Lovis Corinth, Umarmung

Etching, 1915

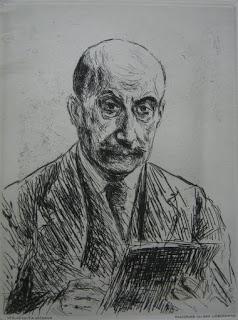

Max Liebermann, Selbstbildnis

Etching, 1917

Max Liebermann, Amsterdammer Judengasse

Etching, 1908

All of the artists whose work decorates this post (except Maria Uhden, who died in 1918) were persecuted by the Nazis, driven from their teaching posts, forbidden to work or exhibit, their work publicly mocked and destroyed. Although only a small proportion of the “degenerate” artists were Jewish, many suffered terrible anxiety about their fate at the hands of a state machine seemingly intent on wiping them and their art from the face of the earth. Some of the stories are beyond sad. Perhaps the most prominent German-Jewish artist in the last decades of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth century was Max Liebermann, the man who imported the Impressionist aesthetic into Germany. When he watched the Nazis march through the Brandenburg Gate in 1933 in celebration of their election victory, he rather memorably declared, Ich kann gar nicht soviel fressen, wie ich kotzen möchte. ("I could not possibly eat as much as I would like to throw up."). Liebermann died unheralded in 1935. In 1943 the Nazis thought it necessary to notify his 85-year-old widow Martha, who had suffered a stroke and was bedridden, of her imminent deportation to Theresienstadt concentration camp; she killed herself before the police could arrive to take her away. Another artist, Franz Heckendorf, not himself Jewish, organized a kind of “underground railway” in Berlin to help Jews to escape to Switzerland; for this he was arrested in 1943 and sentenced to ten years’ hard labor in the potash mines, the prosecution failing in their attempt to push for the death sentence.

Franz Heckendorf, Landschaft

Lithograph, 1921

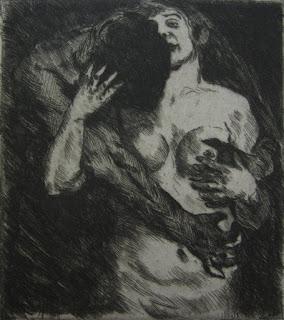

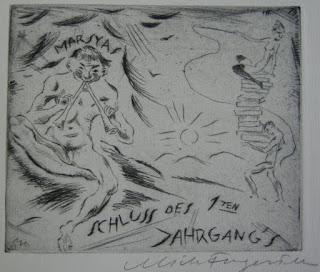

Michel Fingesten, Marsyas

Etching, 1919

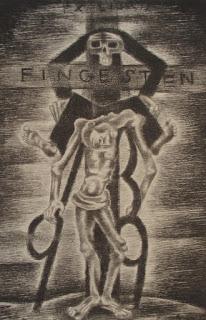

A particularly bitter twist of fate awaited the etcher and painter Michel Fingesten, an interesting artist who supplied a Surrealist strand to German Expressionism. A close friend of Oskar Kokoschka, Fingesten was a prominent artist in the 1920s, but as he was a Jew the doors closed on his career in 1933. After this he created very few large-scale prints, and concentrated on creating exlibris bookplates for private clients. In 1936 Michel Fingesten fled Nazi persecution and took up residence in Italy. This probably seemed a sensible option at the time – his mother was an Italian Jew, so he was comfortable with the language and the culture. But it proved to be a disastrous choice. Fingesten spent the years 1940-43 in Fascist internment camps, and though he was liberated from the Ferramonti-Tarsia camp by British troops on 14 September 1943, he died just weeks later on 8 October 1943 from complications of injuries sustained in an earlier bombing raid.

Michel Fingesten, Exlibris Fingesten

Etching, c.1939

If Michel Fingesten's virtual erasure from art history proved the effectiveness of censorship, the revival of his reputation in recent years has proved its ineffectiveness. Starting with admirers of his ex libris (which have been the subject of a catalog raisonné by Ernst Deeken), other aspects of Fingesten's art have been reassessed. In 1994 Norbert Nechwatal published Michel Fingesten: Das Graphische Werk. In 2008 the Robert Guttman Gallery in Prague held the exhibition The Unknown Michel Fingesten: Paintings, Prints and Ex Libris from the Ernst Deeken Collection, with an accompanying catalog. There is also a dedicated Michel Fingesten Collection at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Of the artists featured in this post, the following had work hung in the most famous Entartete Kunst exhibition: Ernst Barlach, Heinrich Campendonk, Lovis Corinth, Conrad Felixmüller, Rudolph Grossmann, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Karl Hofer, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Gerhard Marcks, Ewald Mataré, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Otto Schubert.