Eine ästhetische Erziehung © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

I have been reflecting on the endless hours I’ve spent acquainting myself with the contents of the Kunsthistorisches Museum and the Belvedere in Vienna, and feeling grateful for the riches I carry around in my memory as I drive Brisbane’s visually polluted highways. I revisited those galleries like the lines of a familiar poem. I adopted those visits as a daily ritual, as habitual as drinking coffee. I seized those delicacies as daily necessities. Reading Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Discourses that he presented to the Royal Academy in the 1770s and 1780s, I grasp all at once how valuable those seemingly idle hours were, how integral to my learning (Reynolds, 1997: 98):

‘Whoever has so far formed his taste, as to be able to relish and feel the beauties of the great masters, has gone a great way in his study; for, merely from a consciousness of this relish of the right, the mind swells with an inward pride, and is almost as powerfully affected, as if it had itself produced what it admires. Our hearts frequently warmed in this manner by the contact of those whom we wish to resemble, will undoubtedly catch something of their way of thinking; and we shall receive in our own bosoms some radiation at least of their fire and splendour.’

Reynolds’s discourse on imitation (VI) strongly defends the relevance of ‘the antients’ (sic) and the mastery of ‘the old masters.’ Rather than stifling our inventiveness, he considers an ongoing communion with the time-honoured masters the only path to inspired invention—‘however it may mortify our vanity’ (1997: 106). ‘Invention is one of the great marks of genius;’ he (1997: 98) writes, ‘but if we consult experience, we shall find, that it is by being conversant with the inventions of others, that we learn to invent; as by reading the thoughts of others we learn to think.’ The artistic poverty of our time and locality may have less to do with dedicated arts funding and more to do with a disdain for ‘the antients,’ a malaise that even Reynolds lamented in his own time and situation. He ‘venture[d] to prophesy, that when [the ancients] shall cease to be studied, arts will no longer flourish, and we shall again relapse into barbarism’ (1997: 106).

After Hans Leinberger, Maria mit Kind (c. 1515/20)

It cannot be denied: Brisbane lacks the cultural riches of Vienna, and a native Australian painter is debilitated in her artistic education unless she transplants herself to Europe for the daily nourishment her chosen career demands. Sheer optimism and hard work are not enough: the mind needs substance in order to grow, and it grows toward that which it focuses on. Joshua Reynolds (1997: 98) cautions us, ‘The mind is but a barren soil; a soil which is soon exhausted, and will produce no crop, or only one, unless it be continually fertilized and enriched with foreign matter.’

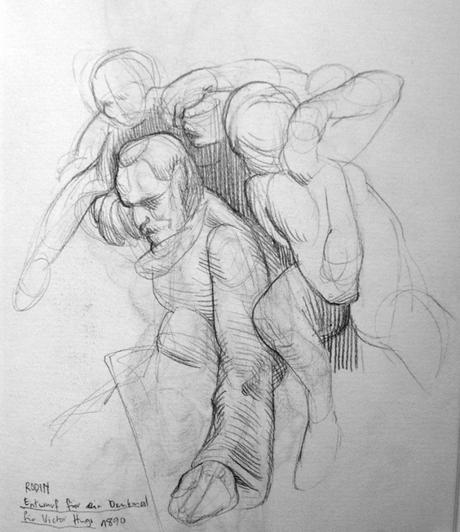

After Rodin, Entwurf für ein Denkmal für Victor Hugo (1890)

It is of utmost importance, then, to give our minds every opportunity to be enriched. If we permit ourselves mediocre habits, our efforts will soon follow. Reynolds (1997: 98) is very firm on this: ‘It appears, of what great consequence it is that our minds should be habituated to the contemplation of excellence.’ I’m reminded of Delacroix’s (2010: 20) chiding himself on lapsing into trivial distractions, writing in his journals, ‘Poor fellow! How can you do great work when you are always having to rub shoulders with everything that is vulgar. Think of the great Michelangelo. Nourish yourself with grand and austere ideas of beauty that feed the soul. You are always being lured away by foolish distractions. Seek solitude. If your life is well ordered your health will not suffer.’

After Czech sculpture, Maria mit Kind (c. 1390/1400)

Australia’s focus on employment, activity, early rising, physical exertion, and contempt for any who dare to think they are ‘above all that and better than us’ sucks one into a cycle of inconsequentialities and mental tiredness that offers very little nourishment and even less opportunity for tending to one’s thoughts. I realise with greater certainty that being in Europe is no luxury, but an indispensible part of my education. Without this first-hand contact with Titian, with Rubens, with Van Dyck, with Raffael, I would not know what painting could be. I would turn to inferior teachers, and unknowingly trust them with my education. I would observe the work of my peers and take notice of their race to absurdity in their pursuit of novelty. I would bring my questions to walls of badly-applied paint, poor drawing, and punch-line titles instead of to excellence, and my work could only suffer. A familiarity with real excellence is indispensible in one’s aesthetic education.

After Titian, The three ages of man (1512-14)

For as original as we strive to be, we are always influenced by our surroundings and by those we associate with—we constantly imitate. Reynolds (1997: 99) suggests it would be better to absorb the thoughts of old masters than what is currently fashionable, or attempting to turn inwards. ‘The greatest natural genius cannot subsist on his own stock: he who resolves never to ransack any mind but his own, will be soon reduced, from mere barrenness, to the poorest of all imitations; he will be obliged to imitate himself, and to repeat what he has before often repeated.’ We need a deeper source than ourselves, a more reliable one than our peers.

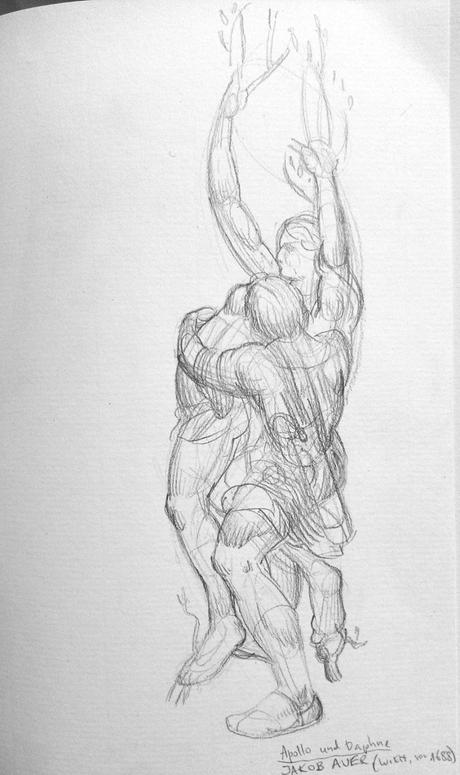

After Jakob Auer, Apollo und Daphne (vor 1688)

Our individuality comes not from ourselves alone, but is formulated by our own perspective on the work of others as well as what we see in the physical world. Instead of a narcissistic cycle of imitating our own work, we might gain from the successful labours of others. We might accelerate our learning by discovering the physical world through the eyes of the masters. And we might truly challenge ourselves by taking them not as gods but as rivals. Raffael was but a human being, and we have the advantage of being able to learn from him and to push further than him. Reynolds encourages more than unthinking plagiarism, but a ruthless competition, an outstripping, a struggle to steal from the past and improve on it. Having thought their thoughts, we bring our own hand and conceal our theft in our own inventions. Our brush borrows shamelessly, but our thoughts are combined in a way that is entirely our own, and it is from here that our originality stems. Reynolds (1997: 96) leaps to our defense: ‘I am on the contrary persuaded, that by imitation only, variety, and even originality of invention, is produced.’

After Rubens, Die Heilige Familie unter dem Apfelbaum

‘We behold all about us with the eyes of those penetrating observers whose works we contemplate; and our minds accustomed to think the thoughts of the noblest and brightest intellects, are prepared for the discovery and selection of all that is great and noble in nature,’ (Reynolds, 1997: 99). So let us not take our situation lightly, for nothing of consequence comes out of isolation and mental starvation.

After Theodor Friedl, Amor und Psyche (1890)

Delacroix, Eugene. 2010 [1822-1863] The journal of Eugene Delacroix. Trans. Lucy Norton. Phaidon: London.

Reynolds, Sir Joshua. 1997. Discourses on art. Ed. Robert R Wark. Yale: New Haven.

I began the above self-portrait on my arrival in Vienna two years ago. It has suffered many iterations, growing and transforming with my own ideas and observations and abilities. My constant struggle with this painting became somewhat representative of my own aesthetic education, and its thickening layers of paint akin to my deepening understanding. The yellow Reclam book is, natürlich, from Schiller. x