For Riccardo C.

because to be eucalypts / they have to shower sometimes in Hell. —Les Murray

To explain why Edoardo Reja—who was born in 1945 to Slovenian parents at Lucinico, a small fraction of Gorizia with a horizontal sundial beautifully painted in light cobalt-blue—is a major figure in contemporary Italian football is necessary to explain why the history of his region has become a field of which sport writers would do well to take notice. They have not always done so. Friuli has been considered a safe, dull haven for the Christian democratic party, with a welfare state 75 years old and reasonable race relations, small and remote enough (even in times of world war) to be dismissed as happy in having no soccer history; none, at least, to which historians need bother to attend.

Within living memory, even the most passionate Udinese supporters sometimes felt like that. Since the mid-1990s, however, two major changes have caused Friuli to reassess its footballing history and the histories of which it has formed part, so that it now has things to say which call for the attention of others. Edy Reja was an actor of genius in at least the second of these changes.

ENCIRCLED LANDS: FRIULI’S FOOTBALLING HISTORIOGRAPHY AND THE MANA WHENUA

The first—about which I will write only briefly here, though it is necessary background—was the opening of Udinese to the Commonwealth of soccer nations participating in the UEFA Cup, following their determination to consider themselves, however hesitantly, denizens of the Italian first division: a stranded, often hopeless affair which stretched its roots back to 1980, when manager Massimo Giacomini led Udinese from relegation to the achievement of lifting the Mitropa Cup. Commonwealth history had been a lesser aspect of the history of soccer in Italy (founded in 1896, Udinese is, after all, the second oldest club after Genoa in the Serie A), always sidelined by the greater themes of the Northern rivalries.

Football in Friuli had been a history of colonization, further sidelined by the still obscure process of replacing the old scars of war and imperialism. Finding themselves marginal to the history of both soccer and Empire, the inhabitants of Gorizia in 1947, two years after Reja’s own birth, were incorporated into Italy again; in this second annexation, important landmarks of the town and several peripheral districts came under Yugoslav territory, like the Kromberk Castle, the railway station and the old Jewish cemetery. If Reja’s parents ever took the young Edoardo in pilgrimage to Sveta Gora, where the Goriška plain joins the Friuli plain with a flock of crazed, speck-sized pigeons, their bilingual family (trilingual, really, adding the furlan, whose proper revival was still to come) would have felt president Tito’s special fervor—the maddening irregular clinking of Communist ideas, moving like frantic shadows beneath the odometer of winter melancholy.

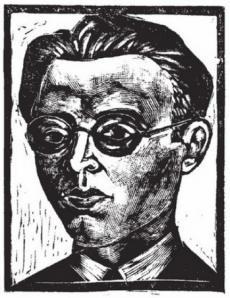

Sporting events such as soccer matches were intended to promote a spirit of harmonious coexistence that remained an ideal at least until the implementation of the Schengen Agreement by Slovenia in 2007. In this transition, a major soccer figure for the region has been Ciro Bilardi, a holding midfielder native of Ischia with some propensity for scoring goals, lean and feisty as shown in this picture, who emigrated to Udine and became both a product and an agent of the kind of globalizing processes one associates with the northern hemisphere of soccer. (One should also begin considering a small yet persistent fixation with African roots, lately claiming that Ghanaian internationals are the most able, among the food-gatherers of the football pyramid, to understand the Word of Soccer in the European scriptures.) Bilardi’s history paves the way for the unique perspective of 1983, when Udinese, at the time in which the team was still surviving relegation with various degrees of threat, had on its books one of the all time greatest playmakers, the Brazilian Zico. The owl of Minerva, in soccer, follows many flight paths.

The still photograph shown below, capping the Brazilian’s triumph by framing his arms stretched out in a V shape, is a rare masterpiece of cinematic architecture. Like the reverse shot indigenous to the filmography of pre-colonial Australia and New Zealand, Zico’s ancestral mana whenua, a sacred identity of joy and sovereignty, to employ a term used by Polynesians of the Pacific world, beams over the grey sponsor of AGFACOLOR, a series of photographic materials produced in Germany, since 1932, after the Agfa-Farbenplatte, the ‘screen-plate’ emulsion associated with negative films, while the other man on focus (his coach, I take it) is sneaking behind to congratulate the hero—heavy Russian-style coat, hat like in a horse race, and the pale cigarette burning ashes a few inches from the champion’s subjugating white teeth.

Whenua may mean either ‘land’ or ‘placenta’. And indeed, Zico’s awkwardly fragile knees seemed shiny and fragrant like a stone through which water drips from a little-used faucet. Though player (and therefore mariner) of extraordinary skill, Zico did not become a settler; the two-way commerce he embodied did not endure so far east. And it took a patient retracing of its genealogy, from the stadium in Udine back to the original canoe in which the first ancestor arrived, for people to connect with mythical figures and spirits of cosmos in the land.

Reja’s parents, watching the Brazilian play would have felt like listening to the music of distant accordions, in the part of Gorizia that gave off the smells of married middle-class ladies, silvery Viennese waltzes, and the grab bags of itinerant vendors who came all the way from the grim old squares of Nyírség—a Magyar region wrapped in birches and dreamy veils of mist. For Friuli, a small people caught up in fractures and divisions, as for Maori and Pakeha settlers alike, like the great historian Judith Binney explained, the past is spoken of, however reluctantly, as ‘before (not behind) us’.

Bilardi and Zico should be mentioned together when we turn to the second transformation of Friuli’s footballing historiography. ‘Colonization’ denotes the occupation of soccer lands by emigrant peoples desirous of maintaining the culture they bring with them; ‘colonialism’, on the other hand, seems predominantly to denote the domination, by means of empire, of at least one culture by people of another. In the experience of soccer in Friuli, the two phenomena became often inseparable, while also happy to remain both in use. Zico’s majestic compass or Oliver Bierhoff’s surgical headers—easily identifiable with the cultivation of ruthless warriors as a national German style of playing, in opposition to the Garibaldian adventures of legendary South American outlaws and guerilla-fighters—served to simplify an oral consciousness of vast complexity and sophistication, whose central concept is that the power of football, its mana whenua, is related to ancestral lands acquired through occupation or war.

It is at this juncture, a significant addition to the mobilizing memories of earlier wandering and prophecy, that soccer in Friuli turns into Fabio Capello’s long-jawed history. Exceptionally well-traveled and educated (he is, among other things, something of an art connoisseur), and yet somewhat bulky and encroaching, like a piece of artillery from the 1910s, Capello understood what soccer had to offer him, if he could guarantee to the game a kind of transnational treaty. Increasingly using an iron fist to impose, by law, a concept of playing as individually alienable on the ethos which held football identities together, he recognized sovereignty in the sense of property, but withheld the implication that property entailed a capacity for alienation. (To alienate one’smana, after all, would be unthinkable if not in a context of zonal marking that is being strictly enforced by means of binding power.) Threatening land sales and confiscation, and treating the chiefs of the locker room with the brutality reserved for refugees in a shelter, Fabio Capello began his metamorphosis from Christ-figure—like Arrigo Sacchi, the ultimate Messiah of the 4—4—2, a man acquainted with unspeakable grief and betrayed by his disciples as he exhausted their physical resources—to Moses-figure, a first-rate leader who is continually forced to prefer the practice of warto a gospel of peace and universal love. As it is well-known, Capello’s talent for settlement and sovereignty ultimately gained him the recognition of a mission from the Crown of England, a powerful and conservative federation with a great deal to shape and a vast experience in the exercises of colonial power and its criteria of verification and falsification.

The second revolution in Friuli’s football—and economics—has happened in the last fifteen years as coaches increasingly urbanized and modern, such as Alberto Zaccheroni and Luciano Spalletti, set up a tactical tribunal to hear claims by various groups that Capello’s work at A.C. Milan (or the Treaty’s promise of steely defensive mechanisms), and by implicationmana whenua, had not been fulfilled. It is vital to understand that these have been claims not of right but to sovereignty, implying that the Treaty was, and is, an agreement between two modes of playing—the zonal marking, reluctantly supported by fans on the terrace, against innovations like the three-man defense or the out-and-out wide strikers that one could see in the Angloworld. There are other lands, mostly in the Austro-Hungarian or Eastern European commonwealth, where indigenous peoples claim to retain footballing sovereignty in some sense akin to mana whenua, but only in Friuli has regional style of soccer been held conditional on the observance of a treaty of Capello’s kind. This has pressed Udinese towards a condition unusual in both football and historiography, and has generated an extensive interest, not yet widely known outside Italy.

It is from this point, too, that one should consider Edoardo Reja’s work—among the work of many others, like Luigi Delneri, from Aquileia, who retained a liminal briskness that almost evaporates from the early days of Christian-Democrat feudalism. Like bourbon over branch water, or a captain swearing to his soldiers during a military campaign, Delneri’s application of pure zonal marking principles shows that the distinction between enthusiasm for war and concern about its consequences is rarely clear-cut. Within this framework, the footballers develop a picturesque, syncopated style, audible and delightful only to a well-tuned ear; they find their respective slot among the clumps of a sunken landscape that is as divided as the refractory windows of Friuli’s barracks during what was once known as the naja, a long stretch of winter in the army service, when salvation is a single, damned pathway with a shrubbery of snow-scarfs, shots of grappa and stained letters from home.

THE PERKS OF BEING A GENTLEMAN IN THE DISTANCE

It had been clear since the outset of his technical career—a hurried, often convoluted trajectory from the youth team of Pescara, through an unsuccessful promotion playoff with Torino, to the international comeback of Napoli early in this decade—that Edoardo Reja was essentially uninterested to place his coaching under the spurious and elaborate heraldry of Nereo Rocco. This is at least surprising, indeed fascinating.

Reja the player, after all, had a protracted history at Spal with his lifelong friend Capello. His deep reluctance, perhaps, may explain why in so many cases mutually hostile administrators declined to follow the recommendations of this strongly individual coach and decided instead to send him on his way before time with a gracious letter of thanks. (Even in the current degradation of the soccer market, with its frenzy about firing, it is hard to imagine among the employers anyone presumptuous enough to borrow Reja’s peculiar character: that severe, sermon-reading uncle of Serie A football.)

Dunga and Reja aspire to a nonchalant, Frigian, undulating belt of through-balls, whose neo-classical declivity and gentle Arcadian slopes can only be the results of years of earth moving.

In Friuli, the practice of catenaccio, meaning “door-bolt” and referring to a highly organized defense, allowed Triestina to achieve a surprising second place in 1947. The system, routinely misunderstood as a cynical and unforgiving way of interpreting the game, is in fact designed to provide a steely foundation to the guile and grace of an attacking parterre. Rocco’s idea of football, moreover, is a chief contribution to the ethos of AC Milan; it is easy to argue that the epitome of this stern discipline was embodied, historically, by the four-men rossoneri backline of the 1990s, with Tassotti, Baresi, Maldini and Costacurta wedded to each other like a hoary-headed groom to a fiery young bride. This iconographic program, connecting Rocco to his ancient Teutonic and Saxon ancestors, is so pervasive that it can be compared, say, to the Argentinean Neo-Republican architecture or to the Gothic Revival in England. Not all of the footballing patrons in Friuli, of course, needed to believe in Rocco’s legend, like eighteenth-century Whigs in London, but most did: from Capello himself, who tried to conflate the craggy tutelage of the old maestrowith social mass-housing, to Cesare Maldini and especially Enzo Bearzot, who emerged victorious in the World Cup of 1982.

Reja must have formulated an opinion about these glorious predecessors. What exactly his thoughts are is impossible to know. But, unless one embraces the entirely unsupported theory that, as a tactician, he is a kind of secret Jacobite, everything seems to point to a significant area of remote detachment—the characteristic liquidity of Trieste that can be traced back to the Habsburg market. Political and poetic undertones pass by the elusive details of Reja’s personality. He is clearly a person who is not easily pleased. He may also be a respecter of persons only up to a point and therefore a man who could find hard to evoke, in turn, respect and warmth. (This is particularly true of players, like Mario Zarate, whose career efforts can be indexed alphabetically under ‘T’ for ‘tantalizing’ and ‘S’ for ‘stupid’.)

While the dressing room of AS Roma involves an implementation both dense and juvenile of the liberal principles of Catalan football—taking the patriotic plan of Guardiola’s faction to the point of literalness—the atmosphere at Lazio is stiff. To take in the present characteristics of the two local Roman teams feels like comparing the ‘superb solitude’ admired by Rousseau with the natural, enveloping ruins of the temple of Vesta at Tivoli. To alter arrangements involves extreme mortification. A mason-architect may try to improve his estate, but only as long as he does not aim to become master. Some players feel a genuine affection for Reja, and enjoy his company; others simply act in terms of relative equality out of flattery. It is crucial to exercise professional tact, for everyone fears to be brusquely ‘excommunicated’. As for the fans, it is clear from any given season, either mild and consistent or schizoid, that the boot could as easily be on each other foot.

In comparison with his ancestors in Friuli, Reja looks like a kitchen gardener or a peasant who had emerged from a field of white asparagus, scissors in hand, to take the wig and turn professor. As a man, he emerges from the physical and psychological devastation of wartime Lucinico, where dozens of heavy trunks on the main square and thousands of automatic bullets represented a desperate, ill-fated attempt by the Austrians to block the surging Italian army near the Isonzo river. As a coach, he likes to tactically strip his opponents, and to depict formations unsparingly, back and front, as if painted by Lucian Freud. Like Polonius in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, who sends Laertes off to Paris with the advice to watch what he wears, ‘for the apparel oft proclaims the man’, Reja sends a substitute to the pitch with a warning, as if position and features spoke of a person’s status—and it is only fitting for a Slovenian of Gorizia to understand how a technicallingua franca, with dialects differing from place to place, is necessary for announcing a public identity and establishing social bonds.

Such deliberateness seems like pedantry to a younger generation of footballers but to Reja’s clients it is infused with the skill of a Kapsberger, a watch-maker who fires a satirical volley of puns to his own clients to see whether they are worthy of his late objects, satisfying himself with merely screening them rather than selling to them, and knocking down the shop-door if necessary. With this posture, Reja had arrived at the locus classicus of the craftsman in Friuli football, the same position currently occupied by Francesco Guidolin. Not until Reja’s later tenure at Lazio, however, did it become apparent how much of his policy is in the footprints of Carlos Dunga, another innovator whose progression, despite his deep tactical wisdom, has been variously punctuated by interruptions and temperamental episodes. Dunga’s portfolio of work with Brazil is a powerful manifesto for hybrid footballing shapes. Reja works just as hard, taking hours to survey and rough out an entire design. Interestingly, the career of both coaches has taken a sudden plunge, almost like a botanist who had lingered for too long on the soccer park in search of evergreens, or a conductor who had spent too much time gazing into the orchestra pit in search of hefty engineering techniques and did not realize that certain solutions, thought to be integral to the game, felt out of fashion.

Good taste in football, at least according to a definite school of thought, is always a rhythmical affair. It deals with passing. It lets business flow in, calmly and ideally from the middle of the pitch. (The other corollary to this theory is potentially unsettling, that to insist on long passes to the wings would be a socially base mana whenua.) Dunga’s aspirations are to be found in the fluid serpentine of Hogarth’s ‘line of beauty’ and the smoothness described by Edmund Burke in his Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful—something that reached its perfect expression in curving trajectories, in the way the baroque was altered into the rococo.

Dunga’s style presents several analogies to Reja’s use of a sort of ‘point blank’ midfield, the dead center of a formation, the axis on which a pair of pivotal passers, similar but not symmetrical, allow an increasingly evident transition between two different systems of playing: the ‘diamond’ shape within a 4—4—2 and a fully-fledged 4—2—3—1. Now a playmaker makes a comma, curling a short-range pass, and there, pointing to another spot, where a more decided turn is proper, he makes a colon; at another part, when an interruption is desirable to break the view, a parenthesis; now a full stop, and then he begins another subject. (It is a hard responsibility to manage such device, and arguably Reja never had a player with enough experience, a Pirlo-type or a Modric-type, to practice and improve this mechanism.) Even so, Reja is right to suggest that the accentuation of a lopsided structure is the epitome of a modern, intricately literary style of football. His chief contribution here, carried out in difficult circumstances of personnel and wanderings, has a breadth and simplicity of effect that looks forward to a new generation of landscaping—as for Guidolin’s experiments in Bologna and Mazzone’s trials at Brescia—freer in appearance, if no more effortless in fact, than Rocco’s posture of pater familias applied to soccer. Dunga and Reja aspire to a nonchalant, Frigian, undulating belt of through-balls, whose neo-classical declivity and gentle Arcadian slopes can only be the results of years of earth moving. This scheme had not received its primary impetus from literature, but football in Friuli always hides a moral allegory. Capello stands against the background of this topographical bent like a James Joyce: the successful, polyglot modernist. Bearzot’s charisma stems from the deceptive, matter-of-fact self-fashioning of Italo Svevo, the banker-writer whose prose sums up the allure of fog and the seduction of carnival. Reja, instead, is more remote. He is rather like Avgust Černigoj, an avant-garde painter who introduced collage in fine arts and, in 1924, helped with the mounting of the first Constructivist exhibition in Yugoslavia; like his fellow Slovenian, Černigoj ran all the gamut between nostalgic innuendo, showy erudition, neurosis, snobbery, aesthetic obsession and infuriating charm.

In his mature style, looser than Dunga’s and more allusive, the overly emblematic in Reja gave way to the metaphorical. The aesthetics of his run of play was now widely enough understood to be read without commentary, even though some players still tried to enclose it and punctuate it with clumps at each performance. Beyond the soccer parks of Italy, Reja’s finely nuanced language of tactical design was being spoken across the Alps. The name of Friuli evoked an idea of innovation, exchanged, if imperfectly, among the furnaces, coalmines and canals of Northern Europe.

Educated in Brazil, well-connected, adventurous, erudite, a first-class observer of the Italian league, Carlos Dunga was perfectly equipped for imperial adventures in the World Cup (that great game of technical espionage). His tenure with the green-and-yellow Seleção can be seen as that of a Western ruler who is fighting to establish a secular, modern state in the face of the old Portuguese forces of tribe and footballing religion. It could have ended in triumph; or it could have ended in a turbulent defeat, among whistles from the automobiles and ill-tempered gestures of the referees. Media intelligence was desperate for information on Dunga and suggested that his tactical innovations might cost him the price of the whole journey. Edoardo Reja offers overall a different case-study—that of a general who insists on fighting the battlements on the outside from a curious triangular, turreted, ironstone building left behind from the times of World War I.

It is not by chance that Reja’s technique against the enemy customarily relies not on constant pressing or wing-play but on effects of artillery, gunning their deadly shells from a distance of several yards from the forefront of the action. The Italian expression centro nevralgico, literally ‘neuralgic center’, nicely captures stimuli pertaining to physiology, the twisted roots of wine-making, and the kernels of the nervous system. Never as during wartime has this bundle of meanings been pushed to an extreme.

In the night between June 2 and 3, 1915, a heavy Skoda mortar was placed and reinforced in the square of Lucinico by Geza Lajtos von Szentmaria, captain of the retreating Mörserbatterie. Its action was devastating. While many Italian soldiers died almost by neglect, the raid’s goal was essentially a defensive maneuver, a sort of bloody high-line defense.

Like opera, the soccer of Nereo Rocco depended on immensely elaborate processes for the suspension of disbelief, and it was always on the brink of the ridiculous. As gracious as its results might be said to appear, however, Reja’s art retains a deep sense of gravitas, and it is always in touch with war, ethical salvation, and modern town planning. Reja’s work, moreover, is imbued with a measure of Romanticism, in the sense that as soon as killer passes and traditional through-balls were going out of fashion, he sought to reinvent the role of the deep-lying playmaker (as Italy reclaimed canals in the 1950s). To the towering crags of the lone strikers, and the savage underforest of those who are supposed to defend against him, Reja would like to substitute the hyacinth dell; to the ruinous cottages of man-marking, to replace the gazebo of harmonious zonal marking. The progress of Lazio and Napoli in recent years almost rendered invisible Reja’s sheer success in imitating nature. Yet it should be his restorations to testify to the widening public awareness of these two teams, if only Reja could place his seal of approval to the unveiling of a blue plaque set with lopsided, picturesque asymmetry on the imaginary Hampton Court of international coaching. ♦