There’s a huge genre of “Parents from Hell” memoirs. Tara Westover’s is intensely gripping.

Her mom practiced midwifery and was much into herbalism, “essential oils,” and homeopathy as their alternative to conventional medicine.

Father “Gene” ran a junkyard and construction business, into which all his kids were dragooned. In lieu of ordinary safety precautions, Gene relied upon the Lord. But the Lord was not reliable, and OSHA’s writ did not run here. The book is a litany of nasty accidents, including two car crashes, one probably leaving Tara’s mother brain damaged. At ten, working in the junkyard, Tara barely escaped from inside a forklift loader dumping tons of scrap iron, her father oblivious to the danger. A brother was severely burned using a torch after having been doused in gasoline.

Before that, Tara decided to go to college, to Brigham Young University. One older brother had similarly escaped the Westover la-la land. Tara crammed alone for the college entrance exam and scored well. Lying to BYU that her home schooling had entailed a rigorous curriculum, she was accepted. Only at college did Tara begin to grasp the depth of her ignorance and outsiderhood.

Long story short, she winds up with scholarships to Cambridge and Harvard, and a PhD in history.

But the real story is Tara’s wrestling with her relationship with her family — and with her own identity which, throughout, remained shaped by that relationship.

Tara eventually figured out that her dad was, well, nuts. Bipolar, to be specific. I attended a talk she gave; asked whether the religious extremism made him crazy, she said it was really the other way around. But the nuttiness and religion obviously fed each other. Yet even while recognizing the pathology, Tara remained infused with a powerful tropism to belong to this tribe, hardly able to conceive of a personal identity exiled from it. (This power of tribal belongingness is seen in our politics.)

Her education entailed a series of epiphanies. I was gratified that one came from reading John Stuart Mill (who tops my own hit parade of thinkers), on how social conventions repress women, which “moved the world” for her.

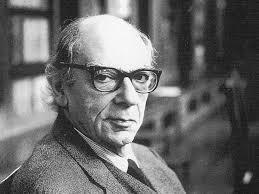

Berlin

She also learned of Isaiah Berlin’s two concepts of freedom: external versus internal coercion, the latter a function of irrational beliefs and fears. Tara knew that applied to her, yet extrication was an almighty struggle. She suffered a paralyzing mental breakdown.

Toward the end I was like, “enough already,” impatient with Tara’s inability to break the hold of her toxic family and its absurd religion. It’s so revealing about the human mind. Tara surely had an extraordinary level of cognitive intelligence to overcome her educational deficits and achieve what she did. Yet she struggled to free herself from ideas she knew were irrational and messing up her life.

But the book has a happy ending — it is really a “triumph of the human spirit” book. Though nothing suggests Tara ever relinquished Mormonism, she finally did kiss off most of her immediate family, saying she hasn’t seen her parents in years.