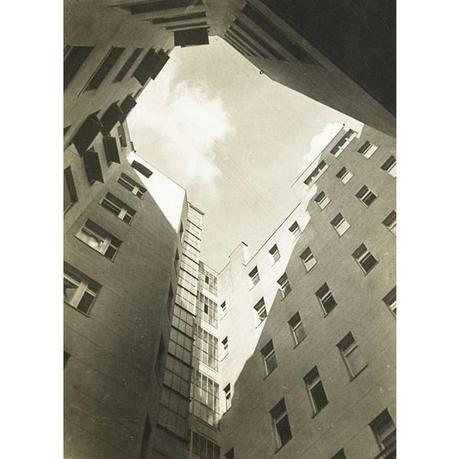

City Heaven, Imre Kinszki

Afew years ago, still operating under the dazzling, jackknifed hand of David Mitchell, English novelists seemed to enjoy a roller-coaster thrillride and to produce echo-chamber pieces where the plot is made by a maze of interlocking pieces. Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, of 2004, brings the reader from an imaginary Pacific diary circa 1850 to a dystopian, post-apocalyptic future; each narrative and dramatization is connected by the use of recording devices, and by the end Mitchell lets the story-line bounce back to its inception, as though echoing a distant foghorn. What in Mitchell remains a swan-dive—a serene, ageless, buoyant rumble—in Tom McCarthy becomes almost titanic, as if the author, throwing in an occasional elbow, felt the necessity of a high-wire athleticism and as if the interlocking system could only work properly by pushing aside parabolic blocks of sound.

A writer specializing in scientific knowledge and Latourian networks of sense, McCarthy is seeing now his second novel, Men in Space, released in the United States and packaged as the work of a “young and British Thomas Pynchon.” As Stephen Burn observed on the New York Times, the template for this book is to be found as much in postmodern fiction as it is in William Gaddis’s midcentury masterwork, The Recognitions. The preoccupation with acoustic devices and a radio dial, moreover, recalls Ismail Kadare’s The File on H, from which derives the sardonic set-piece of the disoriented police agent who tries to spy on a character and is progressively frustrated by the intimation of dullness involved in his task. But what is interesting in McCarthy’s rich and encyclopedic text, following a stolen pious painting from Sofia to Prague and formally dedicated to the theme of disintegration in Central Europa after the fall of Communism, is not limited to literature.

Men in Space and its elastic mosaic of viewpoints succeed in organizing the ‘transitional geographies’ that accompany the Czech Republic during its redrawing of borders as a metaphor of soccer (and sports in general). One of the book’s shuttling middlemen, Anton Markov, is an emigrant Bulgarian referee who is presented for the first time reminiscing in a kind of Joycean interior monolog the circumstances in which he awarded a contentious penalty kick to CSKA Moscow. Markov’s “apprehension of synchronicity” underlies the scenes of the book where football takes a parenthetically prominent role. The players on the pitch are seen as they “slide across its rich green surface, pool balls over felt. . . organizing themselves into rows and phalanxes, then breaking apart and reorganizing, like some living algorithm. White lines and boxes channel them, imposing structure on contingencies of movement, herding chance into patterns.” For much of these moments, the reader feels like in the hall of mirrors in Charlie Chaplin’s The Circus, and indeed Chaplin steps in at the end, like a benevolent guardian, “ducking and scuttling into some alleyway as he runs from baton-wielding cops.” In this way, the experience of soccer is made to leap, to become musical. Like jazz, the sport has a communal appeal, bringing a live excitement that is scarcely captured by a record or carry over to broadcasts—the kind of intensity that can be oppressive at home can be liberating when diffused through a crowd of people.

Tom McCarthy, at times, agrees to mellow or tune down his multiplying, philosophical ambitions. It is here, in these sloping pages, that we find some of the most gorgeously ragged sport riffs, caught across the lawn or against whitewashed plaster walls, like the cracked statue of the discus thrower next to a gigantic iron cast of Stalin, which reminds the spectator of Pompeian torsos fossilized by lava. Rusty wires protrude from arms and thighs, “trumpet-like tubes that nestle in the grass;” but even this broken suburban battlefield retains the capacity for movement: “there’s a gymnast swinging round the handles of a pommel horse, but his arms have snapped off at the wrist, leaving him rotating in the wrong dimension, through the lawn’s surface.” For the navigator of this book, sport is the map room, ranging from the shameful secrets around Dubcek’s murder to the ellipsis as a visual motif. ♦