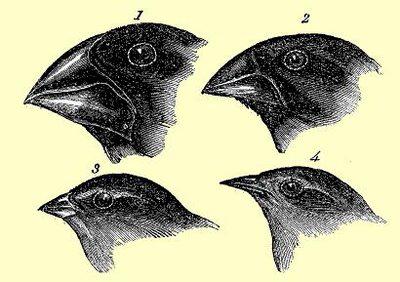

{in the thirteen species of ground-finches, a nearly perfect gradation may be traced, from a beak extraordinarily thick, to one so fine, that it may be compared to that of a warbler. I very much suspect that certain members of the series are confined to different islands. . . —Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle}

‹

6 October. Champions League matches, near the beginning of each season, resemble freshwater lakes, particularly old ones; before the competition becomes too intense, they sometimes have very species-rich endemic faunas of fishes, snails, crustaceans, and other invertebrates. This has long been known.

In biological terms, seemingly monophyletic groups of closely related species coexisting in the same area are often referred to as “species flocks.” Without defining matters too rigidly, it is evident that the genome of certain tactical shapes, a 4—4—2, say, or a 4—2—3—1, is what permits teams to survive and to speciate rapidly inside such Champions League lakes. (Once, when I was thinking of Bielsa’s Chile and the sheer amazement that its polymorphic population of box-to-box midfielders induced in me, I was reminded of a theory advanced in 1933 by Bernhard Rensch, who, in an attempt to explain the growth of Lake Titicaca in the Andes as a biotic environment, proposed three mechanisms to account for the richness of the lake faunas: (1) repeated colonizations from rivers leading in and out of the lake; (2) speciation in different portions of the lake, triggered by external factors; and (3) an accumulation of species through a fusion of previously existing bodies of fresh water.) The existence of “species flocks” has raised a number of interesting questions, two of which have not yet been muted and keep buzzing in my head: can the presence of closely related tactical schemes in a single Champions League lake be explained by speciation? And are these technical resources encouraged or refuted by the principles of the Cup’s competitive exclusion?

Unable to discover any major geographic barriers within the Champions League as an ecosystem other than its subdivisions, I turned to Group A, which offers a remarkable coexistence of Bayern Münich, Napoli, Manchester City and Villarreal. I immediately recognized that no other choice could have been more convincing. I would not be persuaded, in fact, that it is only an incidental byproduct of the general genetic restructuring of the Champions League in its group stages that one could have the possibility of isolating so distinct behavioral types such as Napoli’s reactive 3—4—2—1, Bayern’s archaic 4—4—2 (whose attacking interpretation, the so-called 4—2—4, does not amount, at least in my view, to a distinct assemblage), Villarreal’s highly exportable, Brazilian-tinged 4—2—2—2, and finally Manchester City’s default 4—2—3—1. The group, as a whole, betrayed a strong Mendelian flavor, like the circumstances producing genetic changes in neighboring footballing populations.

The recent match between Bayern and Manchester City, which the Germans won by 2-0, brought this awareness to an interesting level of hybridity. (It took me a long time to understand the impossibility of that fixture ever being repeated, either through parthenogenesis or sexual reproduction.) Watching the tactical macromutations of these two teams reminded me of Charles Darwin’s work with the finches, and the transformation of their beaks to different types of food. Bayern’s attacking weapon remains the employment of “inverted” wingers. Manchester City, on the other hand, has two masked playmakers on the wings, who tend to drift inside, and this is without mentioning at least one striker (and possibly two more on the bench) in a “false nine” position, and the hybrid trequartista, a muscular solution recently favored also by AC Milan. At set pieces, moreover, the English defenders shaped themselves in two distinct lines: one in zonal marking position, and the other offering man-to-man protection—a crucial, ultimately ineffective, eminently environmental solution that seems similar to the premating and postmating mechanisms of the Hawaiian Drosophila.

What would a Darwin, a Huxley, or a Koelliker have thought of this spectacle of hybridity? We must ask which of two individuals would in the long run leave more offsprings: individual A which, like City, can produce several morphs, each partially removed from competing with its brothers and sisters; or individual B which, like Bayern, has only one kind of offspring restriced to a single tactical niche? (Presumably, my guess would be that is a new ‘invader’ was already specializing in one of the subniches, it would almost surely displace the resident polymorphic species from that subniche.) Attacking full-backs, inverted out-and-out wingers, and false playmakers are a frustrating model, so difficult to visualize that it shows electrophoretic differences from the tactical matrix a single player is supposed to represent—a mad dance of allozymes and isozymes whose phyletic lines are split apart from each other. Ernst Mayr, an evolutionist who spent much time studying rare modes of speciation in animals, observed that

there are some special cases of persistent hybridity, typified by Rana esculenta [the water-frog shown here in picture] and some American fresh-water fishes, in which the paternal chromosome set is invariably lost in meiosis, and restored by mating with the respective paternal species. As successful as some of these stabilized species hybrids may be in the short run, they appear to have little long-range evolutionary success (Toward a New Philosophy of Biology, 375).

Yet the zoological speciation may not be the most probable explanation for what happened. An ancestral English species especially ill-suited to serve as source of colonists of new Champions League environments, Manchester City illustrates the paradox by which Mancini’s teams, as it is well-known by now, contain what appeared to be embryos, delicate little skeletons within the skeleton once they leave England’s (or the mother’s) abdomen. While others show just the hard parts, the reptilian tactical skeleton of City is modified for swimming, but also the faint impression of soft tissue, resembling the silhouette of a dolphin. Watching the preparations for European dominance at Manchester City is like attending an exhibit of Jurassic shales or Cambrian fossils in a paleontological circle in Württemberg: the scientific significance is immeasurably consequential yet remote, and it may trigger revolutions such as amphibians, mammals, art, photography, major-league baseball, and rock-and-roll. Mancini’s losses and gains result from transgressions and regressions and—most suggestively—bear the earmarks, through the jersey, of lacustrine species. ♦

Previously in this series: (Chel)sea Slumber-Song.