With its tight running length—barely stretching to the point of feature length—and stripped-down visual style, Dumbo broadcasts the financial desperation motivating it as if trumpeting it through the trunks of its elephants. After Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved one of the greatest hits in motion-picture history, Walt Disney promptly sank profits into the far more ambitious experiments of Pinocchio and Fantasia, both of which proved to be costly flops. Desperate to refill coffers, Disney took a planned short film adapting a story written for a novelty toy and had his team inflate up to a 64-minute picture to get some money, any money, back into the studio.

With its tight running length—barely stretching to the point of feature length—and stripped-down visual style, Dumbo broadcasts the financial desperation motivating it as if trumpeting it through the trunks of its elephants. After Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved one of the greatest hits in motion-picture history, Walt Disney promptly sank profits into the far more ambitious experiments of Pinocchio and Fantasia, both of which proved to be costly flops. Desperate to refill coffers, Disney took a planned short film adapting a story written for a novelty toy and had his team inflate up to a 64-minute picture to get some money, any money, back into the studio.Yet if Dumbo is, fundamentally, a last-ditch effort to raise money, it must surely rank as one of the most delightful and genuinely creative "cash grabs" put to film. Moving away from the more detailed and expensive oil and gouache background paintings that gave Disney's previous two features their considerable artistic depth, the animation team returned to the more economical use of watercolor for backgrounds. But if the cuter, broader backgrounds lacked the intricacy of Fantasia's vastness or Pinocchio's masterfully modulated sense of scale, they also freed up the animators to focus on more vivid character animation, and one need only compare the expressiveness of Dumbo's baby blues to the more basic facial capabilities of prior characters to see how much the Nine Old Men and the rest of the animators could grow even when taking a studio-mandated step-backward.

The film's plot, even considering the running length, is spare: storks bring a circus elephant a baby boy blessed/cursed with massive ears, and the constant mocking the child receives eventually causes the mother to snap and get taken away from her boy. But this basic plot makes for a story more emotionally gripping than the previous three Disney features by leaving everything to the character animation. Mrs. Jumbo's deflated look when Dumbo does not initially come with the other delivered babies, the fat tears that roll down Dumbo's cheeks when he is ostracized for something he cannot help, the twisted looks of haughty disgust on the faces of the other elephants; all of these serve as emotional gut-punches that give much of the film a heavy sadness that conflicts wholly with the candy-colored sweetness of the backgrounds.

Dumbo himself is a masterpiece, the high- water mark of character animation in Disney's golden period and the standard to which nuanced, expressive character rendering must be judged today. The animator responsible for him was Bill Tytla, erstwhile the animator of hard-edged villains or at least antagonizing characters. He gave Grumpy his visual spikiness, Stromboli his undulating and unstable mass of flesh, and Chernobog his pants-wetting, epic-scale evil.

But Dumbo is something else entirely. Drawn with soft edges, Dumbo has just enough lines to confine him into the shape of an elephant. But the pink of his ears runs fluidly into the gray of his skin, his movement one of grace and clumsiness, the embodiment of innocence that culminates in eyes so blue they stand out even at night. Every action this poor, different creature makes is endearing, from his playful bath to inadvertently getting drunk when he drinks water mixed with champagne. Dumbo never utters a word throughout the film, and rarely makes noise of any kind, but no matter: one look at him and you're as liable to look out for him as his mother. Dumbo would be Tytla's last masterpiece for the studio, and the simple, emotional purity of the baby elephant stands as his finest achievement.

The rest of the animation is no less impressive. Woolie Reitherman handles most of the early scenes involving Timothy Mouse, the Jiminy Cricket-esque figure who looks after Dumbo in his mother's absence. These early Timothy scenes show the same attention to scale that defined Pinocchio's shifting animation, with Reitherman making tree trunks of elephants' legs and stretching the great beasts even higher as Timothy berates them for their treatment of Dumbo, the low-angle shots used to the opposite effect of their theoretical meaning: here, Timothy conveys so much of the audience's indignation that he propels his outrage upward, blowing apart the usual power dynamics of such framing. An earlier sequence of black workers and the circus animals themselves erecting the circus tent upon arriving at their destination suggests that more than one person at Disney was pleased with Sergei Eisenstein's endorsement of their work, for the sequence looks like something the Constructivist would have died to put in one of his films. As sheets of rain stab down in diagonal lines, the animals and employees raise beams and canvas. Cut corners abound in this film's animation, but the striking use of diagonals and grim light convey the energy-sapping slog of the labor. And after the animators strike that would throw off the balance not only of this film but subsequent Disney features of the decade, this sequence's depiction of race and class exploitation comes to be one of the studio's most scathing autocritiques, a depiction of the circus, the ostentatious brand of family entertainment, effectively enslaving its workers, sometimes across generations.

(This sequence, seemingly extraneous, may also have worth for clarifying the role of the crows who appear later in the film. Derided, not unfairly, as stereotypical depictions of black people, the crows indeed dress and speak in perceived black patterns, and the leader of the bunch was even named Jim Crow in script drafts. Nevertheless, as grating and dated as these visualizations are, performance-wise these characters, only one of whom is voiced by a white person, are more complex and defiant than any live-action black character at the time could ever be. Though they join in the mocking of Dumbo's ears, they direct most of their jabs at Timothy and are even stand-offish against Timothy's own forceful nature. They also prove to be the only characters besides Mrs. Jumbo and Timothy to support and encourage Dumbo, even coming up with the trick to give Dumbo confidence to fly. Their animated depiction is still troubling, but the actual behavior of the crows, combined with the earlier look at black employees visually aligned with animals as creates of hard, thankless labor for whites, suggests a rare depth for Disney.)

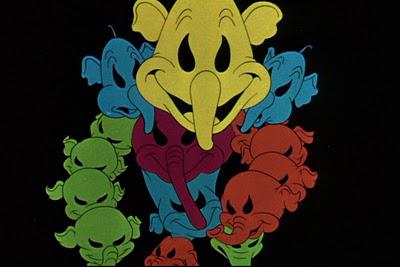

The best animated sequence of the film, however, is also the one that has the least to do with the overall tone of the film. Dumbo and Timothy, both drunk on the spiked water, have a joint hallucination of creepy, neon elephants dancing in the sky. The notorious Pink Elephants on Parade sequence has been lauded and dismissed for its sudden break from diegetic coherence, but it is impossible to deny the power and sinister fluidity of the animation. The nightmarish elephants move like gelatin, jiggling and stretching with abandon as they dance around a jet-black void, a void also seen in the vacant, disconcerting pits where their eyes should be. Obviously, this hallucinatory vision clashes not only with the watercolor softness of the rest of the film but with the reality of inebriation itself, yet it demonstrates one last fitful gasp of Disney's pure artistry before they began to aim in a more commercial direction. Disney films would see such a gonzo burst of neon color again until Eyvind Earle did the art direction on Sleeping Beauty.

With Dumbo, we see the emergence of Disney's patented brand of sentimentality; the studio was already upholding conservative values with Snow White and Pinocchio, but here at last one can see Disney actively targeting the audience's emotions. It proved so successful—earning more than Pinocchio and Fantasia combined at a fraction the expense—that the studio soon learned how to commercialize that appeal, and the studio never truly aimed for the loftiness of Pinocchio or Fantasia again. As such, Dumbo is a harbinger of things to come, more so because of the controversy of the strike that occurred right after completion of principal animation, which might also explain some minor hiccups throughout that didn't receive a smoothing-over. Along with Bambi, Dumbo represented the changing face of the studio and the end of its all-too-brief Golden Age; the studio wouldn't put out another feature of remotely comparable quality until the end of the decade with Cinderella (though 1944's The Three Caballeros displays some of the old ambition), and the familial atmosphere of the workplace was shattered by the strike and Walt's harsh reaction to it.

Nevertheless, Dumbo displays all of the creativity and brilliance of Disney's classic era, from its pleasing style to its emotional devastation—for my money, seeing Mrs. Jumbo confined so-close-yet-so-far-away to her lonely, mocked son and capable only of reaching out her trunk to morosely comfort him is profoundly more disturbing than the flat-out death of Bambi. It's remarkable to see how Dumbo fits in with its surrounding features, sharing the traits that run through early Disney features—the emotional shortcuts of Bambi, the overarching validation of a conservative worldview, even matching animation like Mrs. Jumbo's jail resembling the mobile one Stromboli uses to trap Pinocchio. But it also shows the stylistic variance of these early Disney movies, its watercolor softness radically different from the sharp, edgy oil and gouache of the preceding two films, the impressionistic realism of Bambi, and even the more picturesque watercolor of Snow White. Its pared-down running time makes it perhaps the most emotionally direct of Disney films, but also the one that most effortlessly pulls of its heartstring-tugging. Despite its simplicity, I would not hesitate to rank it among the studio's finest achievements, and in fact I can name no more than three or four Disney films I might find superior to it.