There are many rules of thumb that are used to convey useful generalizations to martial arts students. One that I’ve heard for years is:

“Use as big a movement as you have time for.”

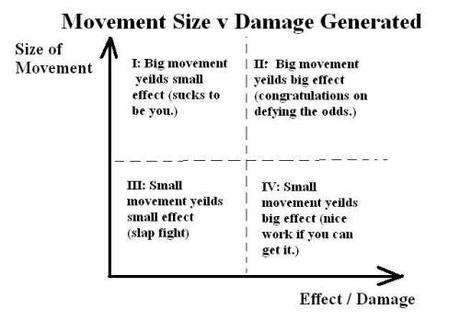

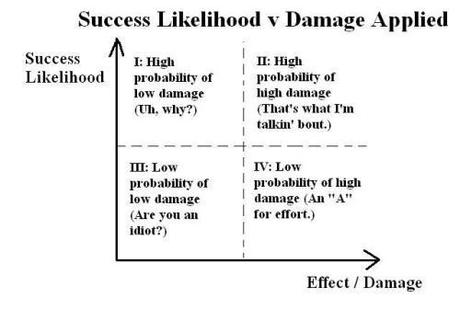

The idea is that big movements are more powerful and, thus, more likely to be effective in damaging/dissuading the opponent–if they land. Big movements use major joints and muscle groups, and allow one to put one’s body-weight into the target. There is, of course, a trade-off that’s recognized in the latter part of the tenet, and that’s that big movements are slower movements and slower movements are less likely to succeed. (i.e. One needs to streamline one’s big movements.)

Like any generalization, this tenet can be valuable only as long as one recognizes where its truth falters. I think this rule of thumb is great as long as the student does sufficient sparring / randori (after they’ve learned the basics.) If one doesn’t (e.g. if one only practices forms,) one can easily develop a false impression of how much time one has against an opponent who doesn’t practice the same art–and how big a movement one can make work. In other words, one’s enemy may dance about pummeling one about the head and neck as one lunges with big (futile) movements.

The aforementioned tenet isn’t the only way of looking at the question of whether to favor big (long/slow) or small (short/fast) movements.

One might also suggest:

“Use as small a movement as will sufficiently damage the opponent.”

Again, there’s a trade-off. While small movements offer relatively high odds of success–they are hard to see and counter–they aren’t as likely to achieve a much sought-after coup de grace (meaning a fight-ender, not necessarily a killing blow.) The risk one faces if one follows this second tenet too blindly and without sparring is becoming extremely fast while unable to punch one’s way through a wet paper sack. This is kung fu movie style martial arts, very impressive to look at but not so so effective in a combative sense.

I would argue that one should take advantage of any opportunity to deliver substantial damage with small movements (quadrant IV of the first graph), but be aware that these opportunities don’t grow on trees. How does one defy the trade-off? As an example, I have found that moving an elbow into the line of attack of an incoming limb can destroy said limb’s effectiveness briefly, offering one an exploitable opportunity. This is extremely hard for the opponent to see and respond to once they are committed to an attack.

So the ultimate question is whether one favors big/slow/low probability/high consequence movement over small/fast/high probability/low consequence movements. As per my second graph I would suggest one finds a way to employ tactics that are as close to quadrant II as possible, while realizing they’re a tall order in a combative situation.

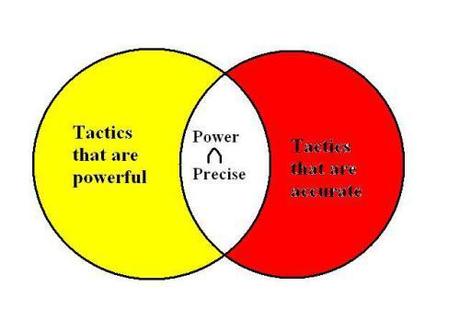

Figuring out how to manage these trade-offs requires a journey to the intersection of accuracy and power. It’s extremely difficult to be precise in a combative environment, everything is in motion and time isn’t aplenty. However, as one fine-tunes one’s technique, one should consider what trade-offs are being made and how one can increase power without sacrificing accuracy and vice versa. Ultimately, it all boils down to practicing conscientiously, constantly, and with as much realism as is safe.

Now I know what you are thinking, “What kind of nerd puts three graphs in a martial arts blog post?”

This kind [Jutting both thumbs in my own direction simultaneously.]

By B Gourley in martial arts, strategy on July 2, 2014.