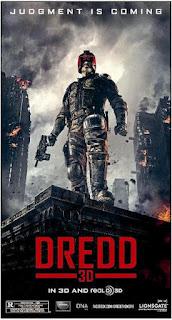

Of the many pleasures to be found in Dredd, Pete Travis' lean, nasty bottle episode of a film, perhaps the greatest is the lack of cumbersome setup that so dreadfully weighs down many comic book films. The only backstory for the protagonist and the world he inhabits is delivered by the main character himself in a terse voiceover that condense the hour of setting and character establishment that has become de rigeur for franchise starters to a mere minute or two. The Earth is an irradiated wasteland, and the only inhabitable area in the remnants of the United States is a vast, concrete-walled region known as Mega City One. Keeping the 800 million boxed-in residents of this massive slum in order are a group of peacekeepers known as Judges, authorized to pass and execute judgment on the street. Oh, and one of these Judges is named Dredd.

Of the many pleasures to be found in Dredd, Pete Travis' lean, nasty bottle episode of a film, perhaps the greatest is the lack of cumbersome setup that so dreadfully weighs down many comic book films. The only backstory for the protagonist and the world he inhabits is delivered by the main character himself in a terse voiceover that condense the hour of setting and character establishment that has become de rigeur for franchise starters to a mere minute or two. The Earth is an irradiated wasteland, and the only inhabitable area in the remnants of the United States is a vast, concrete-walled region known as Mega City One. Keeping the 800 million boxed-in residents of this massive slum in order are a group of peacekeepers known as Judges, authorized to pass and execute judgment on the street. Oh, and one of these Judges is named Dredd.And that's all she wrote. Cut from this sparest of setups straight into a fracas, Dredd (Karl Urban) chasing down a car full of drug addicts as they fire wildly at the Judge on their trail. Set aside but a few more minutes after this swift action sequence to lay out the film's plot: assigned to take a rookie made psychic by radiation exposure (Olivia Thirlby) on patrol, the two head to a towering slum block to investigate a gang message killing. What they find is a 200-story building entirely under the control of a savage gang leader, Ma-Ma (Lena Headey) looking to protect her manufacturing plant for Mega City One's hottest new drug, Slo-Mo. Literally locking the building down, Ma-Ma forces Dredd and Anderson to fight scores of bad guys tasked with collecting their heads.

The resulting film recalls The Raid, another film about elite police forced to clear a hostile complex floor by floor in the hunt for a drug manufacturer. But where The Raid took its pared down premise with distracting severity even as it treated its latent fascism as the elephant in the room, Dredd confronts its endorsement for desperate measures in desperate times with a brutish wit and a clear pleasure in its gory delights. Urban channels laconic, grizzled stars of action films past, the top of his face always hidden behind Dredd's impenetrably tinted helmet visor and his chin always locked into place as it occasionally lets words his through the cracks in his clinched teeth. Urban captures the perverse Platonic ideal Dredd represents as a lawman: he has killed so many in the name of martial justice that he has attained the kind of detached emotional response that is, in theory, the embodiment of what justice should stand for. When the Peach Trees complex thugs fire upon him, he expresses no rage or fear, instead noting simply that they have just committed an offense punishable by death and that he shall now carry out judgment.

Also worth noting is Travis and writer Alex Garland's superb grasp of pacing and flow. A film of nothing but action can be as tedious as an action overburdened with plot. But Garland's script, as punchy and direct as Dredd's occasional dialogue, does not mask the absurdity of its simplicity nor the Manichaean properties of this world. Even when corruption is shown, this serves less to complicate the film's moral absolutism than to reinforce it: if a Judge breaks the law, that Judge will be treated as any other criminal. This deliberately undercuts the impact any twist might have, ensuring that all focus remains on the staging of the action, which is kept fresh enough that it avoids becoming repetitive and dull from desensitization.

But it is Travis' direction that makes the biggest impression in Dredd. The framing and editing of the action occasionally disorients, but Travis makes intelligent of the confining borders of corridors and the open ring of air in the center of each floor. Spatial clarity across a sequence generally holds up even when it disappears a few shots at a time in a hail of tracer rounds. The real achievement, however, concerns Travis' use of 3D to visualize the effects of the Slo-Mo drug, which also passes on its namesake to these shots. Filmed on Phantom Flex high-speed cameras, these sequences slow time to such a crawl that drops of water separate and coagulate in midair, and smoke does not so much get exhaled from the lungs as crawl from mouths like a butterfly worming its way from a cocoon. Travis compensates for 3D's dimming effect by cranking up the brightness for these segments, an ingenious solution that factors in the technology's weakness even as it adds another layer of hallucination to the filmed effect of the drug. Coming hot off the heels of Paul W.S. Anderson's sumptuous use of bright color schemes and slow-motion in Resident Evil: Retribution to get the most dimension out of his three dimensions, Travis furthers the argument that clever B-movie makers continue to use the format in a more inventive, pleasing way than the self-serious filmmakers who look upon 3D as the next major artistic leap.

Dredd also continues the trend of 2012's mid-budget blockbusters vastly outclassing the tentpole features in terms of filmmaking panache and focus of aesthetic and thematic ideas, and all with shorter running times. Hell, Anderson's psychic interrogation with a particularly uncooperative and nasty piece of work, one that turns into a frenetic and surreal battle of mental wills inside the perp's mind, handles the fractured, carnal nightmare of a mental invasion with more visual probability than anything in Inception. Witty but never winking, Dredd is so refreshingly un-postmodern that it may well become one of the few films of recent years to earn a legitimate cult following without being specifically designed to be a cult film. Who knew a work of reactionary fascism would be such a breath of fresh air?