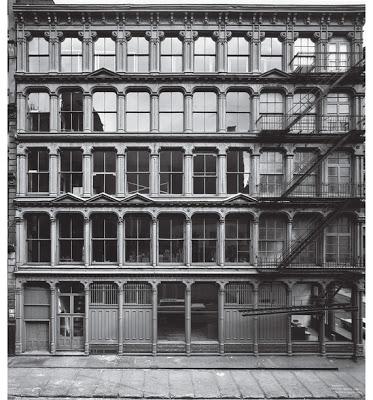

Judd Foundation. Photo Paul Katz/ © Paul Katz/Courtesy; Judd Foundation Archive

A few years ago I discovered New York’s Judd Foundation, the residence and studio of minimalism’s most important exponent, Donald Judd, since 1968. My desire to visit it was frustrated due to it being closed for refurbishment. Its doors finally reopened three years later, in June 2013, and I was allowed a visit a few days before the official reopening.

The impressive 19th-century cast-iron building is located on 101 Spring Street in the heart of SoHo. It’s made up of five loft-style floors - one for each activity, as Judd once wrote. He used the top floor as a bedroom, and it now includes works by some of his close friends: Dan Flavin created a spectacular sculpture out of fluorescent lights in the shape of a series of windows, and Chamberlain had a sculpture made of pressed scrap metal hung from a wall. The next floor from the top had a two-fold purpose: as a games room and dining-room. The next floor was a studio and exhibition area, which today contains a large piece by Frank Stella and designer furniture.

On the second floor Judd placed the kitchen and a closet for the children, including a theater where guests were entertained. And the entrance doubles as a second exhibition space and features a Carl André sculpture and some of Judd’s own works.

Behind this permanent exhibition of works in his own home was Judd’s idea that to understand an artist’s work, one has to see the place in which he works. He asked his sons Flavin and Rainer, current co-presidents of the Foundation, to leave the house exactly as he had left it, to ensure that future visitors to the studio would continue to appreciate this relationship. Other works of note in the Foundation, apart from Judd’s own pieces, are those by Larry Bell, Claes Oldenburg, a fresco by David Novros and furniture designed by Alvar Aalto.

More examples of Judd’s installation work can be found in Marfa, Texas, where he moved to in 1971. There, in the middle of an open field, he was able to materialize his project of a permanent installation, creating a large-scale art piece consisting of 15 gigantic hollow boxes placed outside on a desert-like landscape. Also in Marfa is the Chinati Foundation, which he created with the purpose of housing his own work as well as that of his peers (Chamberlain, Flavin, Oldenburg, Roni Horn) and which echoes his artistic aesthetic and principles on permanence.

Although not content with the “minimalist” label, Donald Judd was certainly interested in simplicity of form, as well as the relationship between objects and space. His work, when taken as a whole, is a reminder to the viewer that often the simpler the art, the more complex its meaning.

His primary field of work was sculpture; he once wrote: “Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface. Anything in three dimensions can be any shape, regular or irregular, and can have any relation to the wall, floor, ceiling, room, rooms or exterior or none at all.”

The Donald Judd Foundation is a tall, magnificent studio, with great ceiling-to-floor windows that allow the interior to be bathed in sunlight, and with a decadent touch added by the floor and old wooden stairs. Its architecture and interior design, and the sculptures and paintings it houses, all come together in one unique space that transports the visitor to time long gone. It begs repeated visits, not least to fully capture the full range of ideas and aesthetic principles the artist wanted to leave us with.