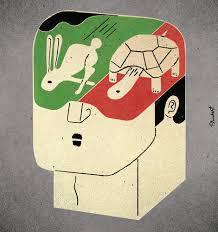

Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow says there are two distinct systems operating inside your skull. “System 1” gives quick, intuitive answers to questions confronting us, utilizing thought algorithms rooted deeply in our evolutionary past. “System 2” is slower and more analytical, used when we actually (have to) think, as opposed to just reacting.

Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow says there are two distinct systems operating inside your skull. “System 1” gives quick, intuitive answers to questions confronting us, utilizing thought algorithms rooted deeply in our evolutionary past. “System 2” is slower and more analytical, used when we actually (have to) think, as opposed to just reacting.

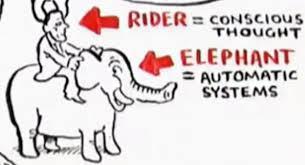

This comports with Jonathan Haidt’s metaphor in The Righteous Mind: System 2 is a rider on the back of an elephant that is System 1.

All this would be fine if System 1 were totally rational, but of course it’s not, and books like Kahneman’s have been taken as debunking the very idea of our being rational creatures.

One key example of how System 1’s decisional algorithms are irrationally biased is undue loss aversion, weighting potential losses more heavily than equal potential gains.

We don’t often encounter coin flip bets, but this bias infects many aspects of human behavior – like investment decisions – as well as public policy. Case in point: GM food. Europeans in particular are so averse to potential risks (an extreme “precautionary principle”) that the truly small (indeed, mostly imaginary) risks of GM foods blind them to the truly large benefits.

Meanwhile, the idea that humans aren’t rational has entered political debate, as an argument against market economics, which supposedly is premised on rational economic behavior (homo economicus again).

Here’s what I (System 2) think. Obviously, we don’t behave with perfect rationality. But rationality isn’t either/or, it’s a spectrum, and on the continuum between perfect rationality and perfect irrationality, we’re far toward the rational end. Our entire civilization, with all its complex institutions and arrangements, is a supreme monument to rationality.

And even when we default to System 1, that is not irrational. Let’s not forget that System 1 evolved over many eons not to lead us astray but, instead, to help us cope with life’s challenges (thus to survive and reproduce; for instance, a loss aversion bias made a lot of sense in an environment where “loss” could well translate as death). So – for all its biases and quirks, extensively explicated by Kahneman – System 1 also has a lot of virtues. In fact we simply could not function without it. If we had only System 2, forcing us to stop and consciously analyze every little thing in daily life, we’d be paralyzed. Thus, utilizing our System 1 – faults and all – is highly rational.

The same answer refutes the critique of market economics. We are far more rational than not, in our marketplace choices and decisions concerning goods and services. Market actors are fundamentally engaged in serving their desires, needs, and preferences, in as rational a manner as could reasonably be expected, even if imperfect. (See my review of Tim Harford’s The Undercover Economist.) Allowing that to play out, as much as possible, is more likely to serve people’s true interests than overriding their choices in favor of some different (perforce more arbitrary) process.

Kahneman was informative about a topic of perennial interest – how people form and maintain beliefs.* Here again, while we fancy this is a System 2 function, System 1 is really calling the shots; and again is reactive rather than analytical. System 1 jumps to conclusions based on whatever limited information it has. Kahneman uses a clumsy acronym, WYSIATI – System 1 works as if “what you see is all there is” – i.e., there’s no additional information available – or needed. System 1 is “radically insensitive to both the quality and quantity of the information that gives rise to impressions and intuitions.”

At the risk of sounding smug, I have always sort of recognized this and consciously try to avoid it, by adhering to what I call my ideology of reality. That is, I try to let my perceptions of reality dictate my beliefs, rather than letting my beliefs dictate my perceptions of reality. I am not a perfect “econ,” but I think I am one of the more econ-like humans around.

* An aside: humans are pre-programmed for belief. Is that a lion lurking? The believer loses nothing if he’s wrong. The skeptic, if he’s wrong, may be lunch. Thus belief is the preferred stance, and people readily believe in UFOs, homeopathy, and God.