4pm production/Shutterstock" src="https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/G82krMDZ74ogds6FDr9HHQ-/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYzNQ-/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the_conversation_464/a9a359605e30c6e 1dff6484ab9440928″ data-src= "https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/G82krMDZ74ogds6FDr9HHQ-/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYzNQ-/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the_conversation_464/a9a359605e30c6e1dff648 4ab9440928″/>

How do people successfully interact with people who are completely different from them? And can these differences create social barriers? Social scientists struggle with these questions because the mental processes underlying social interactions are not well understood.

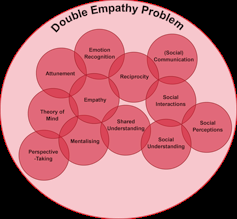

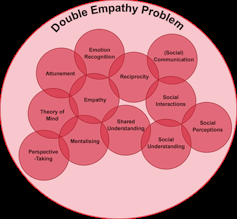

A recent concept that has become increasingly popular is the "double empathy problem." This is based on research into people known to experience social problems, such as people with autism.

The theory states that people who have very different identities and communication styles from each other - which is often the case for autistic and non-autistic people - may find it more difficult to empathize with each other. This two-sided difficulty is what they mean by the problem of double empathy.

This idea is getting a lot of attention. Research on the problem of dual empathy has grown rapidly over the past decade. This is because it has the potential to explain why different people in society can have difficulty empathizing with each other, potentially leading to personal and social problems; from poor mental health to intergroup tensions and systemic racism.

But is this idea correct? Our recent article suggests that things may be much more complicated than that.

Our analysis shows that the theory of double empathy has many shortcomings. It highlights that there is widespread confusion surrounding the very vague concept of dual empathy. Research has also focused narrowly on social issues in autism, without considering other social identity factors that influence empathy between different groups, such as gender.

The theory also fails to integrate the psychological neuroscience of empathy. Instead, it confuses the concept of empathy - that is, psychologically sensing the emotions that other people are feeling - with similar but different phenomena, such as 'mentalizing' (understanding what people are thinking from a different perspective).

Because the dual empathy theory is not well developed, most experiments testing this theory are confusing. Many researchers claim to study double empathy while not measuring empathy. Meanwhile, other studies are being used as evidence of double empathy, despite never intending to test this theory.

Research on dual empathy has also relied heavily on subjective reports of people's experiences (rather than expert evaluation), which may not tell the whole story.

Read more: The science of 'mind reading': Our new test shows how well we understand othersOverall, the analysis of existing research indicates that the central claim of dual empathy theory is not well supported. That is, being similar in identity to other people does not necessarily mean that you have more empathy for them.

This is an important issue that needs urgent attention. There are already signs that the theory of double empathy is being put into practice, despite the lack of evidence. Certain researchers and physicians have begun to argue that because there is a dual empathy problem, healthcare professionals are generally unable to understand their patients with social problems. But there is no reliable evidence for that.

Looking ahead, there is a need for more neuroscientific research into social interaction. We expect that brain imaging technologies such as 'hyperscanning' - scanning multiple human brains simultaneously - will help shed light on how different people's brains interact. For example, this technique can be used to test how similarity between people interacting can influence their brain activity.

To achieve breakthroughs in this area, this technology could be used alongside artificial intelligence. It will be of great importance to investigate whether machines can really empathize with people by seeing whether they accurately interpret our brain waves.

Read more: Increasingly sophisticated AI systems can perform empathy, but their use in mental health raises ethical questionsThe benefits of diversity

It is thought that people who live in more socially diverse places, such as large cities, tend to be more tolerant of people who are different than people who live in socially homogeneous places. Ultimately, they view themselves and others as belonging to the same local community, despite ethnic and cultural differences, and seem better able to consider others' perspectives.

This suggests that spending time with people who are different from us might increase our empathy - something that dual empathy theory does not predict. Ultimately, empathy is not just about our ability to understand someone through their likeness. By spending time with people from different social and cultural backgrounds, we can de-emphasize differences - and discover similarities in other areas.

The human experience is vast and complex. Just because two people come from different cultures or have different communication styles doesn't mean they can't be very similar in other ways. Perhaps their values match or they have similar interests. This insight could have the potential to remove some of the barriers that would otherwise make it difficult to understand and empathize with others.

And sometimes people from similar backgrounds have difficulty understanding each other, yet can still have great empathy for people who are completely different from them (for example, refugees fleeing war-torn countries). Why? Dual empathy theory may not be the best way forward, but it can serve as a springboard for future research to answer these and other questions.

We could really use the social science of empathy to understand these incredibly complex social issues. This could ultimately reduce societal conflict and improve social cohesion - but we need to get research on track to realize this potential.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.