Shortly after the opening ceremony of the 2023 United Nations climate negotiations in Dubai, delegates from countries around the world rose to a standing ovation to celebrate a long-awaited agreement to establish a loss and damage fund to help vulnerable countries to help recover from climate-related disasters.

But the applause may not yet be justified. The deal itself leaves much undecided and has drawn criticism from climate justice advocates and frontline communities.

I teach global environmental politics and climate justice and have been attending and observing these negotiations for more than a decade to address demands for just climate solutions, including loss and damage compensation for countries that have done the least to cause climate change.

A brief history of loss and damage

“Breakthrough” was the term often used to describe the decision at the 2022 COP27 climate conference to finally establish a loss and damage fund. Many countries welcomed this “long-delayed” agreement – it came 31 years after Vanuatu, a small archipelago in the Pacific Ocean, first proposed compensation for loss and damage from climate-induced sea level rise during earlier negotiations.

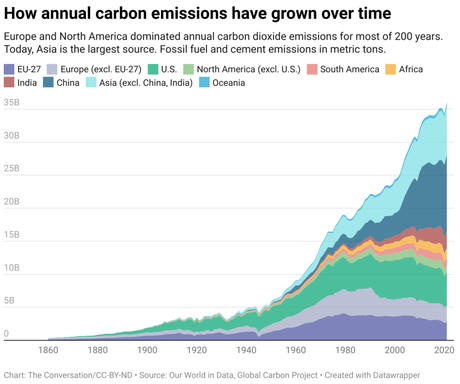

However, the agreement was only a framework. Most details were left to a transition committee that would meet during 2023 to pass on recommendations on this new fund to COP28. A United Nations report outlined at the commission’s second meeting found that funding from rich countries to help poorer countries adapt to the ravages of climate change grew by 65% between 2019 and 2020 to $49 billion. That is still far below the $160 to $340 billion that the UN will need annually by 2030.

As the meetings progressed, developing countries, long wary of traditional financial institutions’ use of interest-bearing loans, which left many low-income countries in debt, proposed making the fund independent. However, developed countries insisted that the fund be housed at the World Bank and withheld the recommendations until just before COP28.

The devil is in the details

While any deal on financing climate disaster damage would certainly be portrayed as a historic victory, further research shows that it should be welcomed with hesitation and scrutiny.

Firstly, the fund contains no details about its size, financial objectives or how it will be financed. Instead, the decision merely ‘invites’ developed countries to ‘take the lead’ in providing financing and support, and encourages commitments from other parties. It also does not indicate which countries will be eligible for funding and vaguely states that this would be the case for “economic and non-economic losses and damages associated with the negative impacts of climate change, including extreme weather events and slow-moving events.” get going.”

So far the pledges have been disappointing.

Calculations of the early pledges amount to just over $650 million, with Germany and the United Arab Emirates pledging $100 million and Britain committing $75 million. The United States, one of the largest contributors to climate change, has pledged only $17.5 million in comparison. It’s a shockingly low starting point.

Also, any idea that this fund represents liability or compensation for developed countries – a major concern for countries with a long history of carbon pollution – was completely dismissed. In fact, it is noted that the response to loss and damage is instead based on cooperation.

In a rare victory for developing countries, funds were made available – even at sub-national and community levels – to all countries, albeit with performance indicators as yet undetermined.

Additional concerns have been raised about the fund’s interim host: the World Bank. In fact, the decision on a host institution was one of the sticking points that almost derailed previous discussions.

On the one hand, the United States and other developed countries insisted that the fund be placed under the World Bank, which has always been led by an American and has historically promoted pro-Western policies. However, developing countries opposed the World Bank’s involvement based on their historical experiences with its lending and structural adjustment programs and pointed to the bank’s longstanding role in financing oil and gas exploration as cornerstones of development efforts.