Andrew O'Hehir argues that it's through public conversation about stories like those of the Duggars and Caitlyn Jenner that Americans now carry on political debate about the role of religion in American life and how sexual abuse is often tolerated, minimized, covered up within families. The old-fashioned kind of political exchanges carried on by means of the ballot box now engage primarily "the fearful, the crazy and the deeply, pathologically Caucasian (overlapping demographics, to be sure)" when the presidency is not at stake.

And so it's a huge mistake, O'Hehir maintains, to pooh-pooh the kind of "low-cultural" conversations we have about stories like the Duggar and Jenner ones. It's a big mistake to insinuate, as centrist intellectuals and the beltway media like to do, that these stories should be beneath the notice of Serious People, since they're stories that involve the lives of people who really shouldn't receive notice, given where they live and who they are.

O'Hehir's rejoinder: it's the narrative of the centrists, their fatuous belief that they stand at the center of what's really significant, that has become a footnote to stories like the Duggar and Jenner stories:

When you observe the intense and unfeigned public response to those stories, and the symbolic media warfare they provoke, it becomes not just meaningless but dangerous to insist that such things are inherently trivial, or serve only to distract the citizenry from Serious Issues and Real News. Caitlyn Jenner and the Duggar family speak to America’s changing sense of itself, and to the shifting fronts in the "cultural war" that Pat Buchanan invoked in his famous speech in the Houston Astrodome, 23 years ago. (I was there!) They are in fact the substance of our national conversation, the central narrative of American political and cultural life in our time. What happens inside the Beltway is a footnote, if that.

Translated: if you aren't willing to get your feet muddy slogging through public conversations about such "low" pop-cultural matters, you increasingly will not count in the kind of culture being fashioned in the 21st century. Like that culture or deplore it, it's where an increasing number of people, notably younger ones, live. If people who think religious ideas and values are important want to have any influence in this kind of culture, they're going to have to stop pretending that only the culture and outlook of the culturally dominant, of cultural centers, counts. They're going to have to engage a world they have not yet sought to engage, as they issue their supercilious condemnations of the shallowness and materialism of a world gone mad with postmodern narcissism and secularism.

And since part of the challenge of this new way of talking about matters like the place of religion in public life and how sexual abuse is handled within families and faith communities is to open the door to conversation, to admit that even authority figures may well be wrong, and to ask questions in a dialogic communtarian context, here's a question I have for you today: Are people like Denele Campbell correct when they maintain that the rate of sexual abuse of minors tends to be higher among people with religious connections than in the rest of society?

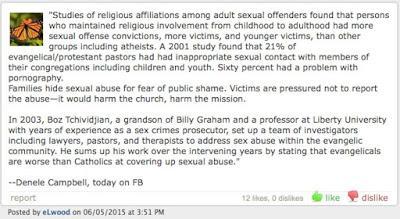

Here's Denele Campbell as cited by a reader called eLwood in an Arkansas Times thread this weekend discussing the Duggar story:

It's interesting to me that Campbell (about whom I know nothing at all, except that Google tells me she has an interesting-looking blog and has published a number of books) is noting here something I noted several days ago: namely, that Billy Graham's grandson Boz Tchividjian asserts that "the problem of child sex abuse in evangelicalism is 'worse' than the problem in the Roman Catholic Church."

These issues seem to me well worth discussing. They are being discussed now, in light of the Duggar story. Sarah Morice-Brubaker, who teaches at Phillips Theological Seminary in Tulsa, has just published a statement at Religion Dispatches, for instance, warning people to be chary about — not to jump on the bandwagon uncritically with — the claim that religious fundamentalism is genetically connected to child sexual abuse, or to the cover-up of child abuse.

Still, if we set aside the assumption that the media focus exclusively on the cover-up of child sexual abuse in authoritarian religious communities (and there are a lot of people connected to authoritarian religious communities from Catholic to Jewish to evangelical ones who maintain that the media are out to get people of "orthodox" faith by manufacturing stories of child abuse in their congregations), I find it interesting that there does seem to be a growing body of evidence that rigid, patriarchal religious systems may spawn abuse of children (and women).

And that those same systems seem inclined to cover up such abuse, to excuse it, to pretend it's not there, and to adopt a hunkered-down, defensive response to anyone wanting to ask questions about this behavior . . . .

Or am I wrong in wondering about these connections? I honestly don't know. And so this is why I'm asking. What I do know is that the rather smug assumption of people with anti-Catholic axes to grind that abuse occurs and is covered up only or primarily in the Catholic church has been blown out of the water by one revelation after another about the kind of abuse concealed in other communities of faith, many of these very authoritarian ones like the Catholic community as represented by its institutional leaders.

And so whatever paradigm we craft to explain these stories of child abuse, that paradigm can't simply lambast the backwards, patriarchal Catholic hierarchy, or blame celibacy or homosexuality in the priesthood for child abuse. The Duggar story counters all of those too easy assumptions.

(Anyone who thinks I offer these observations because I'm a triumphalistic defender of the Catholic hierarchy does not know me or has not read much of this blog. I offer them because I find easy answers to complex questions insulting. They do not do justice to reality.)

Another red herring, it seems to me — again, because it's too easy, and does not do justice to the complexity of a much more mixed reality: atheists good, religious people bad. Atheists don't abuse, people with religious convictions do abuse.

That's too easy. And it lets too many people who need to look in self-critical mirrors before they hold mirrors up for others off the hook, as so many of these glib, explain-it-all-in-five-easy-steps, self-glorifying theories do.

Still: I'm inclined to think that there is, indeed, a connection that needs to be teased out between the taken-for-granted abuse (sexual and otherwise) of children and rigid, patriarchal forms of religion. Perhaps I'm inclined to make that connection because I myself grew up in a conservative evangelical culture in which the corporal punishment of children was taken for granted as a good and holy practice in line with religious values. The American bible belt, the states of the Southeast, are far and away more inclined to approve of hitting children as a means of discipline, polls constantly inform us, than people in other parts of the U.S. are.

I know what it feels like to grow up being beaten — sometimes beaten bloody — by parents quoting the bible as they wield belts or switches, or kick and hit with their fists while telling their hapless victim that God has enjoined such punishment of children's wrongdoing by pious parents. And so it took little to convince me that Philip Greven and Alice Miller are both right on target, when I first read their books pointing to the roots of taken-for-granted physical abuse of children in religious ideologies.

Even though I have my own inclinations and thoughts about these matters, I'm open to hearing other perspectives. What do you think? Is there, in fact, some kind of genetic link between rigid, patriarchal religion and taken-for-granted abuse of children and of women?