Fleisch / Meat (c) Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

Reading Deleuze is a somewhat disorienting undertaking, but not without its rewards. The cascade of words, the veritable excess of words that skirt around the ideas, approaching them from all sides, unsystematic, rhythmic, and hypnotic, seduce us like poetry. One can easily be swept along by the words, so it takes extra concentration to seize hold of the ideas and trace them through the burbling writing. We are not greeted with signposts, but we trustingly hold a thread and allow ourselves to be pulled along.

It is the jolt that his writing gives us that is electrifying and spurs us into activity. The disorienting metaphors short circuit our thinking and force us to question concepts that have become second nature. We inevitably become habituated and even stuck in our patterns of thought and behaviour; Deleuze offers us an escape. What at first seems outlandish is maybe the only thing strong enough to break our habits—habits in both thought and practice.

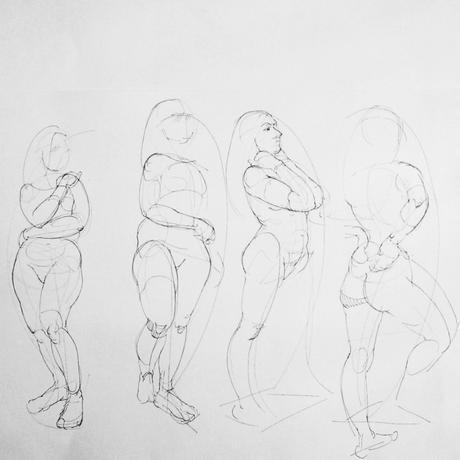

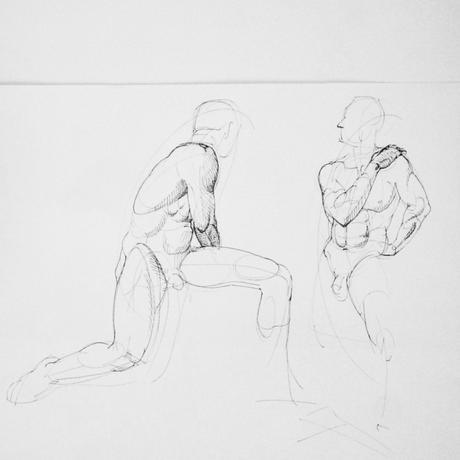

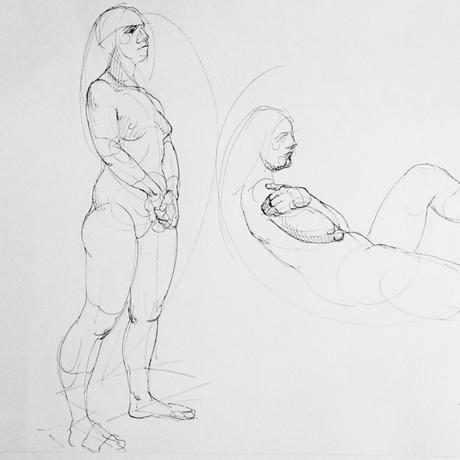

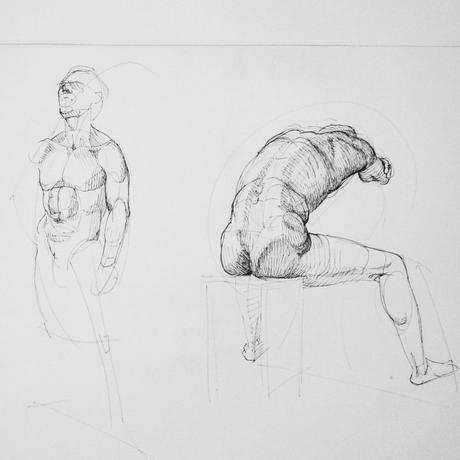

For his book on Bacon is fascinating to me as a painter, not only as a philosopher. It is not only in intellectual discussions that figure and ground have become comfortable concepts; whatever artists call them, if they use words at all, there is much physical evidence that many painters work with such a binary division in mind. It is the kind of thinking encouraged by art history, that of treating figures as if they were stickers that could be lifted and repositioned at will, removable symbols. There are painters who indeed paint in this way: treating the edge of a figure with a biting crispness that severs the two zones with clumsy cruelty. Such paintings haplessly proffer us a paper cut-out against a disconnected stage. In such paintings the edge is a cliff, wrenching an eternity between subject and setting, and betraying the conceptual simplicity of the artist. But there are other painters who recognize the crucial interplay between figure and ground, and who couldn’t conceive of divorcing the two. These painters do not simply fill in the holes around the figure, but work each shape into the other, find two-dimensional rhythms through the image that traverse space in three-dimensionally impossible ways, notice and celebrate fortuitous kisses between distant but aligned objects, and think about the asymptotic turning away of form and the subsequent expanse of flesh to be treated at this intersection, despite its retreat from our line of sight. These painters know that ‘something happens in both directions’ (Deleuze, 2003: 12).

But Deleuze (2003: 6) attempts to break our brains with his deliberations on Bacon’s ‘three fundamental elements of painting’: the material structure, the round contour and the raised image. From the start, he catches us off-guard with unfamiliar terms that we have to chew over a bit, grasp more deliberately, rather than permitting us to feel we are entering the discussion with our concepts firmly in place. Deleuze deliberately disarms us, but this is part of the fun, because as philosophers we know there are not enough words to name our ideas, and as painters we hardly care to give them names, as long as we can form them with our hands. So we follow him trustingly to see where these new terms will take us, what new aspects they will bring to our attention.

Firstly, a new name for the ground, the ‘material structure,’ shakes us out of our habit of thinking of a passive, receding substrate waiting to be animated by the ‘real’ content of the picture. It grants comparable status to the bits around the figure. The concepts of ‘figure’ and ‘ground’ remain faithful to the illusion of space, which urges us to see some things set behind others; ‘material structure’ against ‘raised image’ suggests a more immediate visual interaction. We are urged to notice that the material structure coils around the raised image, seeping into its crevices and constricting the image with a muscular strength of its own.

And the plot thickens: for by naming the intersection between them we draw attention to its significance, and grant this feverish zone a physical presence too. But Deleuze (2003: 12) has more to derail our predictable thought patterns: he insistently describes the contour as a place. Habitually, we would consider the ground to be the setting; Deleuze perplexingly transfers this status to the contour. But if we humor him and deliberate on it a while, a new thought takes shape—that there is something powerful in conceiving of the contour as the site of the action. For while it is not the literal setting in which the subjects of the picture act, it is undeniably the physical territory where image and material mingle, vie for predominance, press upon each other with such force that we must admit that this is where the action indeed takes place, at the quivering border of two shapes, where neither is considered positive or negative but both brandish equal power.

Indeed, Deleuze challenges our worn understanding of ‘figure,’ appropriating Lyotard’s distinction between ‘figurative’ and ‘figural,’ and reserving the capitalised ‘Figure’ for the subject. The figurative comes to stand for representation—which Deleuze (2003: 2) lightly defines as any time a relationship between picture and object is implied. The but the Figure need not always be representational, and to avoid the figurative or representational is not necessarily to turn to the abstract. Deleuze (2003: 8) argues that there is another way to salvage the Figure, to make it work in other less literal, less narrative ways, without dissolving into the drifting Figureless mists of pure abstraction. This is the way of the ‘figural,’ a twist on familiar vocabulary that tries to carve out a different painterly intent. The figural is about ‘extraction’ and ‘isolation,’ and Deleuze (2003: 2; 15) batters us with imagery of escape through bodily orifices, through the bursting membrane of the contour, through screams, through ‘mouths’ on eyes and lungs. The Figure must, demands Deleuze (2003: 8) be extracted from our ordinary and overused figurative approach to painting, and the visual means by which this is done plays on these squeezing and heaving forces.

All this metaphor can send one in circles, but perhaps Deleuze pushes us to circle around the idea because of it’s very unfamiliarity. He stalls us a moment. If we momentarily let go of our representational concerns, we might ponder the middle ground a while. Is there some immovable core of this Figure that touches us more directly than its unaltered exterior? Is there something about the insides of this Figure that should pervade its exterior, remould it, alter the way we choose to apply paint? Many of us already ask ourselves such questions in some manner, whether we trouble ourselves with such intentionally picky language or not. We might still be struck by how much further this thought can take us, once put into words.

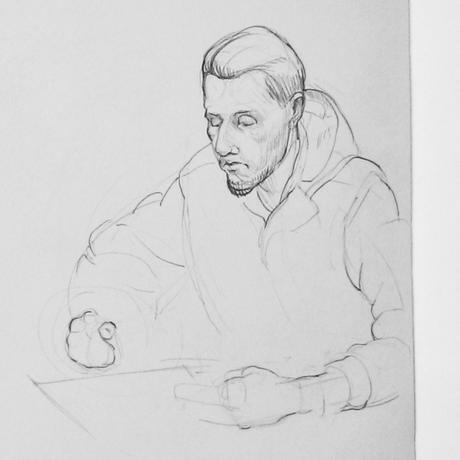

The paint can certainly touch us more directly—Bacon (in Deleuze, 2003: 35) ponders the way it sometimes reaches us by long and slow means through the brain, and other times makes direct contact with the nervous system. Deleuze’s preoccupation with meat cuts to the heart of this matter. Faithful representation results in satisfying deception; other visual mutations prompt entirely other trains of thought that bring us to the core of the Figure with startling immediacy, or jolt us back into our bodies with an immediate sensory experience. Our skins keep us together, stitched up, polished and presentable, though we know we are made of flesh. But to dwell on our meaty composition is something subterranean and sensual, it is an unusual meditation on our physicality.

And paint, in its materiality, seems so well suited to such fleshy contemplation. Deleuze (2003: 22; 23) enters with his high-sounding words—musing on the ‘objective zone of indiscernibility,’ the ‘common zone of man and the beast’ that meat insinuates. Meat, more immediate than flesh, less individual, more raw and yet dripping with a quickly-fading life, is indeed a more urgent, primal way of categorising our substance. It brings us right back to our earthy origins, out of our skins that rendered us fit for society, to a brutish, sub-intellectual level of our existence. As the painter dwells on meat rather than flesh, she touches a nerve, she penetrates us so swiftly that we are enthralled before we have had time to think.

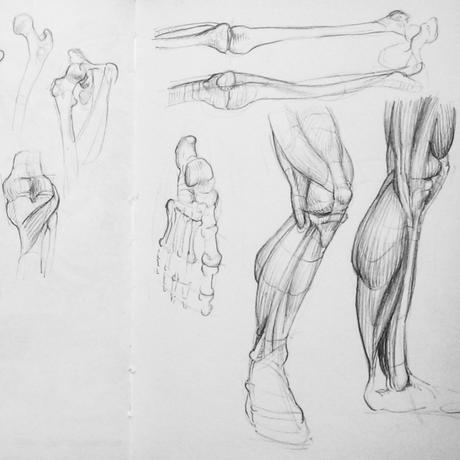

Anatomical studies at the Josephinum, Vienna

Meat is not supposed to be disgusting, however. Primitive and physical, yes, but not brutal. Deleuze (2003: 39) discovers no emotion in Bacon, only sensation. If anything, he finds a peculiar reverence for the essence of a being. An artist—such a physical creature—demonstrates her profound respect for the physical and the earthy in her unflinching confrontation with meat. Perhaps in her incisiveness she cuts us to the marrow—but she ‘goes to the butcher’s shop as if it were a church’ (Deleuze, 2003: 24).

The verbal cycles that Deleuze wrings us through slowly spin an ever thicker web of ideas that challenge the conceptual laziness we so easily lapse into. Perhaps it is nothing but games, but a patient thinker and an investigative painter might yet find such absurdity the very chute through which she can escape ingrained modes of thinking and working.

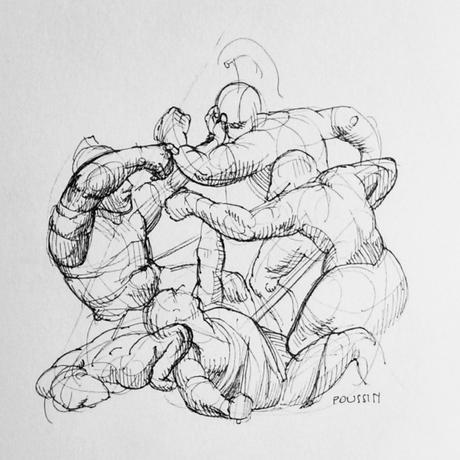

Copy after Poussin

Deleuze, Gilles. 2003. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation by Gilles Deleuze. Translated by Daniel W. Smith. 1 edition. London: Continuum.