By Heidi Noroozy

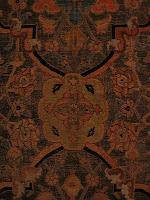

Polonaise carpet in the

Iranian Carpet Museum

Shah Abbas’s military accomplishments included consolidating a fragmented Persian kingdom and defending it against encroaching neighbors. The king also bolstered his country’s economy by intensifying trade between Persia and Europe, whose leaders he viewed as natural allies against his enemies, the Ottoman Turks. Abbas developed close ties with England’s East India Company by giving them special trade privileges and exchanging silk for English broadcloth. He also sent a large shipment of fine silk to King Philip of Spain and Portugal in an attempt to persuade him to give up the strategic island of Hormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, which the Portuguese had captured from the Persians nearly a century earlier. (This mission failed so completely that the Safavid ambassador to King Philip's court was executed when he returned home to Persia.) Not only silk yarn and cloth but luxury carpets also often made their way onto merchant ships and into diplomatic pouches.

Polonaise detail

Some of the finest carpets to come out of Isfahan’s royal workshops belong to a group that scholars today classify as “Polonaise.” The name, a French word meaning “Polish,” is a bit misguided, based on a misunderstanding (more about that in a bit), but Abbas spared no expense in commissioning these unique carpets to dazzle trade partners both at home and abroad. The carpets were made of silk in bold, vibrant colors and often had brocaded areas fashioned from threads wrapped in real gold or silver. Although the foundations were usually cotton to lend the structure durability, separate silk fringes would be sewn onto the ends, giving the appearance that the entire rug was made of the more costly material.Polonaise weavers used motifs that are still recognizable in modern Persian carpets, with medallions in the center, twisting vines along the borders, and floral designs against contrasting fields that look like someone scattered a flower bouquet across a pool of calm water. Other Polonaise designs were more typically European, often incorporating emblems associated with Western royalty, which has led scholars to believe that they were commissioned and made to the customer’s specifications.

Polonaise carpet with the

Polish royal crest

(Residenz Museum, Munich)

Although some historians questioned the carpets’ European roots right from the start, many prominent textile experts persisted in attributing them to Polish carpet factories well into the 20th century. But contemporary accounts show that Sigismund Vasa III of Poland commissioned eight carpets in 1601, and two years later Shah Abbas sent another to Marino Grimani, the Doge of Venice, as a diplomatic gift. Today, nearly everyone agrees that most Polonaise carpets were woven in royal Safavid workshops in the Persian rug weaving centers of Isfahan, Yazd, and Kashan from the time of Shah Abbas’s Golden Age right up until a devastating Afghan invasion put an end to Safavid rule in 1722. And yet the Polish-inspired name has stuck.

Polonaise carpets today are rare, with only around 300 of them known to exist. Some of these rugs belong to prominent museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Residenz Museum in Munich, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Three of the photos I've featured on this page are of a Polonaise carpet I saw in the Iranian Carpet Museum in Tehran. At the time, I was writing my first mystery novel, which centered around the theft of a rare Safavid carpet. I took so many pictures of the Polonaise that I’m sure the guard suspected me of planning a forgery.

Border detail

The surviving Polonaise carpets leave only a hint of their former glory. Many have been worn down to the foundation, making them look more like loosely woven fabric than knotted pile rugs. The once vivid colors have faded to pastels (these dyes apparently adhere better to wool than to silk), and often the gold and silver brocade is either missing or tarnished. But you can still make out the lovely designs and with a bit of imagination reconstruct the vibrant colors in your mind. These carpets are prized as highly today as they were 500 years ago, with some commanding six-figure prices at auction.Before we climb back aboard our time machine for the return journey to the 21st century, let’s take a side trip to the Shrine of Imam Ali in Najaf (present day Iraq), where we’ll slip off our shoes and sink our feet into the soft silk of another of Shah Abbas’s precious commissions: a red and gold Polonaise that he presented to the shrine as a gift. Perhaps it was even another piece of diplomacy, since such a lovely carpet must have gone a long way toward unlocking the gates of heaven to its donor for his generosity. I hope so, anyway. Shah Abbas and his successors deserve a fine reward for giving the world such beautiful treasures.