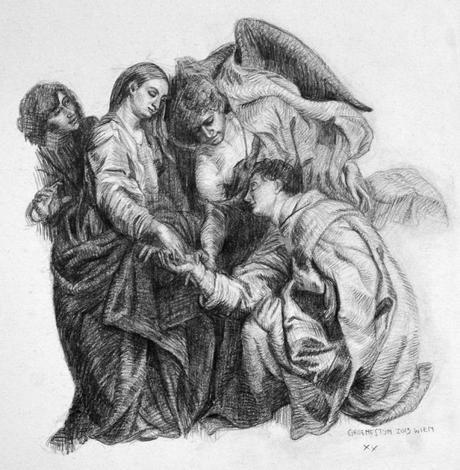

Copy after Van Dyck; Hermann Joseph, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

What is perhaps most fascinating for me in viewing old master paintings, and what seems to be lost on people distracted by clouds of angel babies and voluptuous nudes being fawned upon by the gods of Greek or Christian persuasion, is the representation of the wholly natural third dimension.

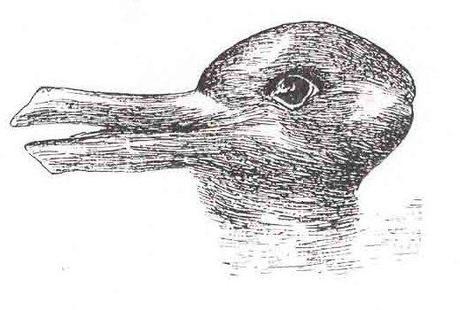

Upon first noticing it, one has not words for this, and thinks it must be something in the paint, in the mixing of colours, in the adeptness with tone. Perhaps exotic ancient pigments. But when your eyes at last adjust to the idea of pictorially representing three-dimensional space, the image suddenly alters under your gaze, like the illusions of Gestalt psychology in which a single image may be viewed as either a rabbit or a duck but never at the one time. Of these duck-rabbit switch images, Gombrich (in Kandel p. 208) thought it significant that ‘the visual data on the page do not change. What changes is our interpretation of the data.’ Your eyes flicker, and you suddenly see that Van Dyck thought not only of the harmonious arc of figures and the sloping, hierarchical diagonal through their hands, but that he also saw depth, and, indeed, has depicted this illusion so convincingly on a completely flat surface. Our modern eyes, however, are actively trained to resist this representation, and conform to flattened compositional devices, colour, symbolism, and—most of all—subject matter. Blinded by our disdain for religion, our modern eyes miss the plane of depth extending back into the picture and fail to recognize just how rare this is in modern painting.

While it’s interesting to take a historical viewpoint of painting and note the evolution from deep to flat, it’s startling to realize precisely where one is situated in this history and to realize the implications this has on one’s understanding of paintings made in ages past. This flattening in art was certainly an intentional educational progression. Viennese painter Adolf Hölzel wrote an influential essay Über Formen und Massenvertheilung im Bilde and introduced the ideas contained within as part of the school curriculum from 1906. We have grown up in the wake of this tradition; we have been trained to see this way, to appreciate our flat canvas for the two dimensions it has, and not to manipulate it to contain more, nor to try to read more than two into it. In this respect, something previously integral to painting has not merely been forgotten but intentionally erased. While Nelson (p. 178) alludes to techniques of looking and making being ‘revised and reworked, gained and lost and rediscovered afresh, over centuries,’ it is clear that some things were not simply forgotten but thrust aside, and the implications of this hang heavily in the air of the gallery today.

Belvedere, Wien

A current exhibition at the Oberes Belvedere, Wien, sheds light on but one aspect of this intentional shift. Die Formalisierung der Landschaft (Shaping of the landscape) exhibition traces the efforts of Hölzel and his contemporaries and followers in the late 1890s to embrace the flatness of the pictorial space, and the general move in the German-speaking countries away from the illusionism that had propelled artists since the Renaissance. Books emphasising negative space in Rubens and the like started to permeate schools—these are the very ideas I recall being plied with, without having the depth-dependent alternative demonstrated to me. To my generation, and perhaps a few before, painting simply is flat, and if one cares to model form one ought to turn to sculpture or installation. Lacking this historical contrast, we have failed to see just how striking this two-dimensional shift was, and, I would venture, have even been cheated out of a fuller understanding of the painting of earlier times. When one can’t see past the plump nudes reclining in courts or the heavy religious topics of Rubens, it probably has a lot to do with lacking the perceptual abilities needed to see the multi-axial compositional genius of his paintings.

Nevertheless, just before 1900, compositional ideas were shifting, and the rise of photography seems to have played no small part in this. Rather than concentrating on illusionistic compositional devices to do with depth or perspective, the fading neutrals of the distance, or the convincing volume of objects, painters and photographers alike were investigating the idea of flat shapes delineating a single-planed composition. The Belvedere exhibition specifically offers the work of the painters Ludwig Dill, Emilie Mediz-Pelikan, Theodore von Hörmann, Rudolf Ribarz, Karl Mediz and Carl Moll as examples, as well as that of the Viennese photographers Heinrich Kühn, Hugo Henneberg and Hans Watzek. The paintings and prints are remarkably alike in their stiff stillness, their solemn but hazy tree silhouettes against the Dachau moors echoing (and intentionally so) the positive and negative ink blots of the Gestalt psychologists.

Taken in this historical context, the paintings are fascinating—just how much were they influenced by psychology, or psychology driven by art? And did photography lend its tone-simplifying characteristics to the thought-process of painters, despite arguments that with the advent of photography painters were forced to diversify, and turn to ornamentation? As Gombrich (in Kandel, p. 109) suggested, ‘The photographer was slowly taking over the functions that had once belonged to the painter. And so the search for alternative niches began. One such alternative lay in the decorative function of painting, the abandoning of naturalisms in favour of formal harmonies.’ Klimt was a prominent Viennese convert to flatness and ornamentation in the face of the possibilities of photography (Kandel p. 115). Nevertheless, the New Dachau artists provide a nice counterpoint of perhaps some of the earliest painting directly influenced by the aesthetics of photography. These aesthetics endure with us today, and not merely through the slavery many a painter has come to have to her camera as a convenient way of freezing her subject, but through the lack of understanding of light and shadow zones and compositional construction when one has done so much of one’s visual learning from the flat, pre-framed and tonally compressed picture plane of the photograph.

Heldenplatz mit Flieder, Carl Moll 1900-1905

Carl Moll stands out in this Belvedere exhibition for his ability to integrate these new ideas without completely sacrificing the old. The gaudy, brightly-coloured and texture-driven paintings of Mediz-Pelikan and Von Hörmann don’t come marginally close to Moll’s delicate representation of lakes and trees and gardens of Vienna. His globes of pruned plants are full and round; their dampened purples vivid in his intelligently considered context, unlike the more crude primaries of his contemporaries. The distance recedes in a harmonious haze of neutralised colours not unlike the true dusty fuzz of a Wiener summer sky. And yet, the shapes dominate and tell the real story, with vast stretches of grass filling broad swathes of the canvas, or expanses of shimmering lake filing the entire foreground. Moll expertly manipulates the modern ideas of flatness without giving up any illusionism. Does he cling to fast to the old? Perhaps, if one only measures success by progress. But I find Moll far more intelligent for his ability to discern between the valuable aspects of all ideas at his disposal to make truly beautiful and engaging paintings. The other paintings may simply be glanced at as examples of their school, but do not stand alone as strong and memorable images.

The march of history need not mean we abandon the powerful techniques left to us by those before. Flatness and ornamentation have been exciting and visually stimulating approaches, and much of the illustration I admire clings fast to these impulses. But to discard other tools simply because they have a longer history is perhaps to deny oneself the tools one needs to truly express something significant.

Heldenplatz, Wien

Kandel, Eric R. 2012. The age of insight: The quest to understand the unconscious in art, mind, and brain, from Vienna 1900 to the present. Random House: New York.

Nelson, Robert. 2010. The visual language of painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique. Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne.