The English, Germans and Italians called it the French disease. The Poles called it the German disease, while the Russians blamed the Poles. In France, the disease was dubbed the "Neapolitan disease" after the French army became infected during the invasion of Naples, Italy, during the first documented syphilis epidemic.

The origins of syphilis - a sexually transmitted infection that devastated 15th century Europe and remains widespread today - have remained obscure, difficult to study and the subject of some debate.

A long-standing theory is that the disease emerged in the Americas and migrated to Europe after the expeditions led by Christopher Columbus returned from the New World, but a new study suggests the true story is more complicated.

Genetic information about ancient pathogens can be preserved in bones, dental plaque, mummified bodies and historical medical specimens, extracted and studied - a field known as paleopathology.

Research published Wednesday in the journal Nature used paleopathological techniques on 2,000-year-old bones unearthed in Brazil in an effort to shed more light on when and where syphilis emerged. The study resulted in scientists recovering the earliest known genomic evidence of Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis and two other related diseases, which reliably dates back to long before the first transatlantic contacts.

"This study is incredibly exciting because it is the first truly ancient treponemal DNA recovered from archaeological human remains that are more than a few hundred years old," said Brenda J. Baker, professor of anthropology at Arizona State University. was not involved in the research.

A complex disease caused by a complex bacterium

Without treatment, syphilis can cause physical deformities, blindness and mental disabilities. As a sexually transmitted disease, this disease has long carried a stigma - hence previous attempts by various population groups to blame outbreaks on neighboring groups or countries.

The story continues

Studying both the disease and the pathogen responsible for it is extremely complex, says Molly Zuckerman, professor and co-director of the Bioarchaeology Laboratories, New and Old World, at Mississippi State University, who was not involved in the study.

"It wasn't until 2017 that researchers were able to culture T. p pallidum for the first time, even though we have known for more than a hundred years that it is the cause of syphilis," Zuckerman said in an email. "It is still expensive and cumbersome to study in the laboratory. There are many reasons why, despite our best efforts, it is one of the least well understood common bacterial infections."

The timing and sudden onset of the first documented syphilis epidemic in the late 15th century has led many historians to conclude that it arrived in Europe after the Columbus expeditions. Others believe that the T. pallidum bacteria has always had a global distribution, but may have increased in virulence after initially manifesting as a mild disease.

"It is very clear that Europeans brought a number of diseases (including smallpox) to the New World, decimating the native population, so the hypothesis that the New World 'gave Europe syphilis' was attractive to some," noted Sheila A. Lukehart op. , professor emeritus of medicine, infectious diseases and global health at the University of Washington, who did not participate in the study.

Syphilis is closely related but distinct from two other subspecies or lineages of treponemal disease, non-sexually transmitted diseases with similar symptoms known as bejel and yaws that were also the focus of the new study.

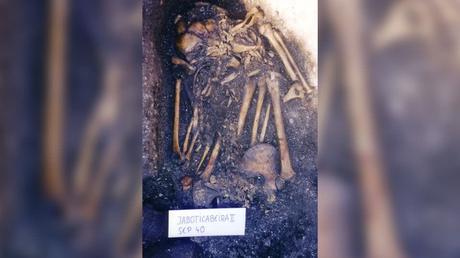

The team behind the new study examined 99 bones from the Jabuticabeira II archaeological site from the Laguna region of Santa Catarina on the Brazilian coast. Some bones showed spores characteristic of T. pallidum infection; the bacteria effectively eat away at the bones, leaving concave lesions.

Bone samples from four people provided enough genetic data for the team to analyze, one of which produced what study author Verena Schünemann, an assistant professor at the University of Zurich's Institute for Evolutionary Medicine, describes as a high-coverage genome, detailed enough for accurate analysis. granular analysis.

The analysis found that the pathogen responsible for the lesions was most closely related to the modern subspecies of T. pallidium that causes bejel, a disease that today occurs in arid regions of Africa and the Middle East and has similar symptoms to syphilis.

The finding adds strength to previous suggestions that civilizations in the Americas experienced treponemal infections in pre-Columbian times, and that treponemal disease had been present in the New World for at least 500 years before Columbus set sail.

Revelations from a bacterial family tree

Schünemann said the new findings do not mean that the venereal syphilis that caused the 15th-century epidemic came to Europe from America at the time of Columbus. In a similar study previously conducted by her team, T. pallidum bacteria were found in human remains in Finland, Estonia and the Netherlands from the early modern period (early 1400s), suggesting that some forms of treponemal disease, if not syphilis, were already in circulation. on the continent at the time of Columbus's expeditions to the New World.

Furthermore, the genome recovered from the Brazilian sample provided a bacterial family tree dating back thousands of years, suggesting that the T. pallidum bacterium first evolved to infect humans as early as 12,000 years ago. It was possible, Schünemann said, that the bacteria had been brought to the Americas by the first inhabitants who entered the continent from Asia.

"I think the story is much more complex than the Colombian hypothesis could ever have imagined," she said.

Mathew Beale, a senior scientist in bacterial evolutionary genomics at the Wellcome Sanger Institute near Cambridge, England, agreed with Schünemann's assessment, saying in an email that the study "reveals the central tenet of the Colombian hypothesis itself neither proved nor disproved - that Columbus's voyage led to the importation of Treponema and led to the outbreaks of the 16th century and then to modern-day syphilis."

"This is mainly because the sequenced bacteria is not a direct ancestor of the strain that causes modern syphilis. ... (I)t is a sister species. This could mean that the various treponematoses were already widely distributed around the world, and could even predate the ancient migration and population of the Americas," said Beale, who was not involved in the study.

"It could also mean that many different treponematoses were present in the New World, and that one of them, only distantly related to the ancient genomes from this paper, was indeed imported by Columbus and his colleagues," he added .

Further research into ancient genomes from around the world could solve the mystery, by clarifying which subspecies of the bacteria were present in Europe and the New World before Columbus's voyages, Lukehart said.

"The bigger scientific question now is not about syphilis, but about the distribution of the three subspecies around the world, especially in pre-Columbian samples," Lukehart said.

"The modern tools available for extracting DNA from ancient samples, enriching treponemal DNA, and obtaining deep sequencing from samples have rapidly expanded our understanding of the Treponema."

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com