When freshwater dried up, so did many megafauna species.

Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Author provided

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

—

Earth is now firmly in the grips of its sixth “mass extinction event”, and it’s mainly our fault. But the modern era is definitely not the first time humans have been implicated in the extinction of a wide range of species.

In fact, starting about 60,000 years ago, many of the world’s largest animals disappeared forever. These “megafauna” were first lost in Sahul, the supercontinent formed by Australia and New Guinea during periods of low sea level.

The causes of these extinctions have been debated for decades. Possible culprits include climate change, hunting or habitat modification by the ancestors of Aboriginal people, or a combination of the two.

Read more: What is a ‘mass extinction’ and are we in one now?

The main way to investigate this question is to build timelines of major events: when species went extinct, when people arrived, and when the climate changed. This approach relies on using dated fossils from extinct species to estimate when they went extinct, and archaeological evidence to determine when people arrived.

Read more: An incredible journey: the first people to arrive in Australia came in large numbers, and on purpose

Comparing these timelines allows us to deduce the likely windows of coexistence between megafauna and people.

We can also compare this window of coexistence to long-term models of climate variation, to see whether the extinctions coincided with or shortly followed abrupt climate shifts.

Data drought

One problem with this approach is the scarcity of reliable data due to the extreme rarity of a dead animal being fossilised, and the low probability of archaeological evidence being preserved in Australia’s harsh conditions.

This means many studies are restricted to making conclusions regarding drivers of extinction at the scale of single palaeontological sites or of specific archaeological sites.

Alternatively, timelines can be constructed by including evidence across large spatial scales, such as over the entire continent of Australia.

Unfortunately, this “lumping” of the available evidence across many different sites disregards the variation in the relative contribution of different extinction drivers across the landscape.

Mapping extinction

In our research published in Nature Communications, we developed advanced mathematical tools to map the regional patterns of the timing of megafauna disappearances and the arrival of Aboriginal ancestors across south-eastern Australia.

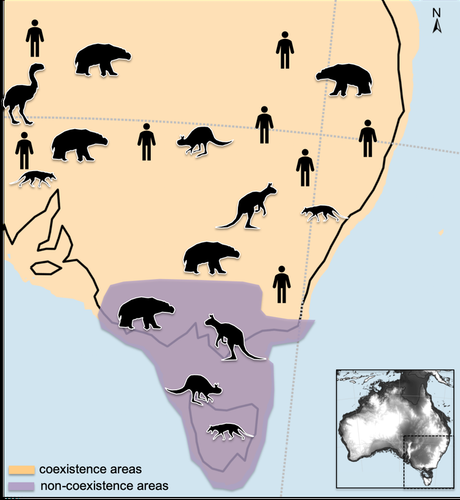

Based on these new maps, we can now work out where humans and megafauna coexisted, and where they did not.

Areas of coexistence and non-coexistence between humans and megafauna.

F. Saltré

It turns out humans coexisted with the megafauna over about 80% of south-eastern Sahul for up to 15,000 years, depending on the region in question.

In other regions such as Tasmania, there was no such coexistence. This rules out humans as a likely driver of megafauna extinction in those areas.

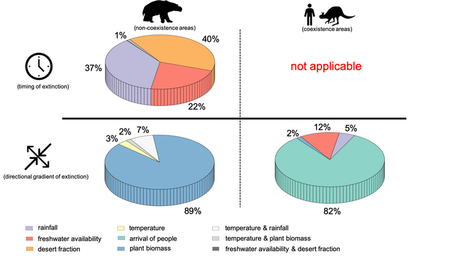

We then aligned these windows of coexistence and non-coexistence in each part of the landscape with several environmental measures derived from climate simulations over the past 120,000 years. This gave us an idea about which factors best explained the timing of megafauna extinction in each part of the landscape.

Despite a major effect on extinctions in areas where megafauna and people did not coexist, there was nothing at all to explain the timing of megafauna extinctions in places where megafauna and people coexisted.

This surprising result suggested that we had missed something important in our analyses.

Connecting the dots

The major flaw in our approach was to analyze each location independently of its surroundings. Our initial model had failed to take account of the fact that an extinction in one place can affect an extinction in another location nearby.

Once we changed our model to incorporate these effects, the real picture finally emerged. We found that megafauna extinctions in areas were they coexisted with humans were most likely caused by a combination of human pressure and access to water.

In the other 20% of the landscape, where humans and megafauna did not coexist, we found that extinctions likely occurred because of a lack of plants, driven by increasingly dry conditions. This doomed many plant-eating megafauna species to extinction.

Relative importance (in %) of variables best describing the timing (first row) and the directional gradient (second row) of megafauna extinction in areas of non-coexistence (first column) and coexistence (second column) of people and megafauna. F. Saltré

Space is key

This is the first evidence that tens of thousands of years ago, the combination of humans and climate change was already making species more likely to disappear. Yet this pattern was invisible if we ignored the interconnectedness of the various regions involved.

This might be just the beginning we need for a new, more nuanced treatment of environmental change in the deep past in other regions of the world.

Read more: 11,000 scientists warn: climate change isn’t just about temperature

More importantly, our results reinforce scientists’ stark warning about the immediate future of our planet’s plants and wildlife. Given rising human pressures on the natural world, coupled with an unprecedented pace of global warming, modern species are facing similar ravages.

—

Frédérik Saltré, Flinders University; Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Flinders University, and Katharina J. Peters, Flinders University

Frédérik Saltré, Research Fellow in Ecology & Associate Investigator for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University; Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Fellow in Global Ecology and Models Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University, and Katharina J. Peters, Postdoctoral Fellow, Flinders University