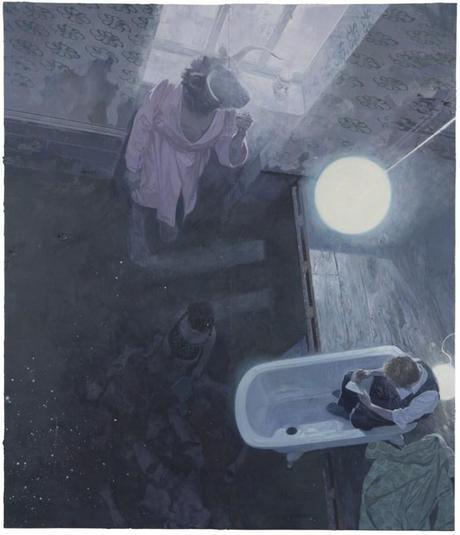

Minotaurus © 2011 Ruprecht von Kaufmann

Ryan and I had the great fortune to meet and talk with the formidable painter Ruprecht von Kaufmann while in Berlin. This man has made a mighty impression on me and his simultaneous humility and aloofness have set a firm example for my own painterly pursuits. His whole being exudes a reverence for his profession; his quiet manner seethes with indignant contempt for the expected mode of operation of the artist. Painting is his only master, and he has humbly followed where its dictates have led, never turned aside by the suggestions, temptations and despairing rejections of those who have sought to drive the direction of painting. Von Kaufmann is a true artist, as the word ought to be used: skilled, inventive, searching and single-mindedly devoted to his task—by the labour of his hands he brings objects into the world which embody his wordless thoughts.

Der Schimmelreiter © 2007 Ruprecht von Kaufmann

Von Kaufmann’s integrity as a painter is rooted in a profound respect for and love of painting itself. Artists, far from being diligent and talented artisans, are generally expected to think at great length about themselves and then string found objects together in shocking ways (or at least arrange them in rows). Yet von Kaufmann’s quiet dedication to painting shows that he cares not for the title of ‘artist’ but for the quality of the work, and finds great satisfaction in the production of it. He diligently works with his hands and raises a family as any other respectably employed person might. In an immersive video in which he presents his work to the students of Laguna College of Art and Design in California, he says so artlessly and truthfully of being a painter: ‘It’s one of the most beautiful professions that I could possibly imagine to be in.’ This sweet and simple statement has stayed in my mind. The more I look at his work, the more I realise that this sentiment is at the heart of it.

Der Schiffbruch mit Wolf (detail) © 2012 Ruprecht von Kaufmann

Von Kaufmann’s delight in the substance of paint is evident in his lascivious handling of it: the thick and gutsy paint is an absolute pleasure to the eyes. He has long been conscious that the visual artist works in physical media, and speaks of his growing awareness of ‘the idea that a painting is an object.’ At first this meant that his paint grew thicker and more audacious, boldly making itself known within the image. And with time it provoked him to challenge his substrate, leading to experiments with painting on rubber and felt, with gashes in the surface, with questioning the most desirable viewpoint, and with merging painting and installation (though, notably, never abandoning painting). It drove him to adopt wax as a medium for pigment, rather than linseed oil, to give a satin glow and a cloudy transparency to the generous lathering of paint. The earthy physicality of painting remains ever at the fore in von Kaufmann’s work, and I think we would do well to seize upon the sensuous strength of paint even if others fashionably abandon it for every material but.

Mittsommer (detail) © 2010 Ruprecht von Kaufmann

Since von Kaufmann’s work is heavily imaginative, reference material can only serve him so far. His strong representational training as a painter is thus reinforced by memory, driven by a genuine fascination with the visual. Again and again he refers to memory, and it becomes clear that he has devoted a large part of his working time to internalising his observations. Small studies, lovely as stand-alone still lives, were born as a means of his absorbing sights. And even apart from these studies, his intersection with the physical world is one of curiosity and deliberate observation:

‘When I see things that I know that interest me and that I want to use in a painting, I look at them very consciously, trying to break them down into the most simple thing that would allow me to memorise how to put that into a painting and how to represent that.’

Painting from memory allows him a vast amount of freedom, and he relishes his early discovery that ‘you can tell people a lot of lies visually.’ But his irreproachable draughtsmanship is ever the firm scaffolding for these imaginative constructions.

Kreuz © 2009 Ruprecht von Kaufmann

Von Kaufmann’s investigations lead him down rabbit holes that make him difficult to categorise, and thus difficult to brand and market. And this is extremely admirable. The difficulty he presents to galleries and collectors is precisely what establishes him as a creative innovator. The market thinks in terms of contained packages fit for profit, making projections based on trends. But a person of real genius concocts something entirely new as if from nowhere. As we wouldn’t expect our favourite bands to churn out the same predictable album every year, but (as true fans) we grow with the band and delight in their growth as artists, there is a real satisfaction in seeing a painter boldly stretch and grow with a searching honesty.

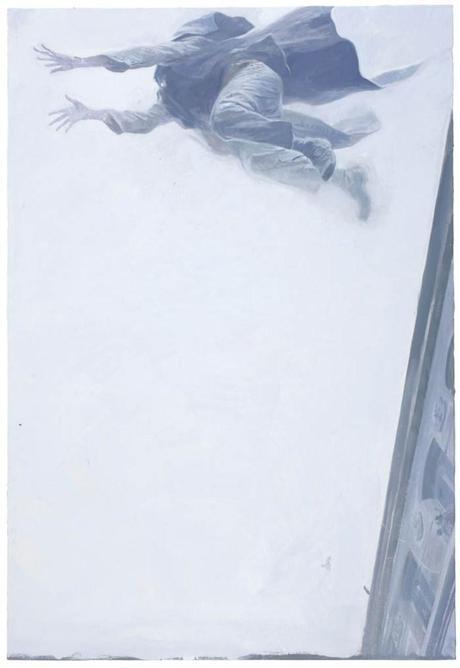

Leap of faith © 2009 Ruprecht von Kaufmann

His quiet disregard for expectations is fortifying:

‘For one thing, I don’t really care. … It seemed pretty clear to me from the get-go that I was never going to have any museum shows or any broader art world acceptance anyway, that this was purely a niche thing.’

Not deliberately shocking, but rather true to his profession, von Kaufmann perseveres on his own path, treading where he must. Collectors may not appreciate the dramatic shifts in his work, gallerists might not consider him a safe investment; these are but small obstacles on the road to being the best painter you can be.

The Pawning (detail) © 2010 Ruprecht von Kaufmann

And this is the heart of it: von Kaufmann knows himself to be a painter. He understands that his work is physical and visual. He knows that he stores memories in his body, and he uses them to weave visual thoughts into objects. Not strictly pouring out narratives, but using subtle narrative cues, he builds counterfactual worlds dense with mood rather than with symbolism. Trained by his sight, he is liberated by invention, able to ‘tweak everything to just fit the composition and the mood you want to set.’ His impressively trained memory enables fluency with his visual language: ‘I actually love, as a drawing medium, on a beautifully prepared canvas, to work with the brush and oil paint. It’s a beautiful way to draw that’s a lot freer.’ Might this sheer love of and reverence for painting well up in our own defiantly intelligent brushstrokes as they do his. We are fortunate to have, after all, one of the most beautiful professions imaginable.