They lure you in from a distance and promise pure aesthetic pleasure: pastel-colored tutus, beautiful girls. Once you get there, look closer. You notice the darkness around the edges; you wonder about the battered foot in the pointe shoe. Degas's dancers fascinate for the same reason as the ballet itself.

A new exhibition, Discovering Degas, offers plenty of opportunities to reflect on the paradoxical beauty of ballet. It opens next week at the Burrell Collection in Glasgow and includes 23 Degas pieces from the museum's own collection, as well as 30 loans from around the world.

Born to wealthy, conservative parents in 1834, Degas discovered his love of opera as a child and began painting scenes from the ballet in 1870. He would remain fascinated by dancers for the rest of his life - he then sculpted them from wax and clay. his eyesight started to deteriorate. At his death, at the age of 83, approximately half of Degas' oeuvre was devoted to ballet.

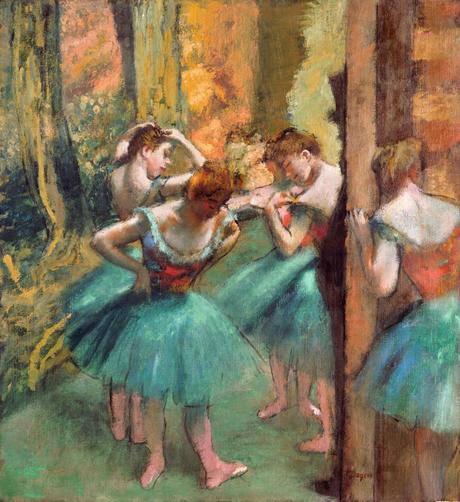

His paintings bear witness to the quiet moments in between: a dancer practicing alone at the barre, or lacing the ribbons around her ankles. Degas was less interested in the glamor of the performance than in the efforts of the dancers in class, their preparations backstage and the mundane that waited in the wings. In paintings such as The Green Ballet Skirt (circa 1896), which are in Burrell's permanent collection, a dancer leans on a couch, averts her gaze and massages her foot. The image brings out a poignant contrast between her beautiful costume and her tired expression. In A Group of Dancers (c. 1898), also on view at the Burrell, three women in tutus huddle in the corner of a studio. Bathed in an unearthly emerald light, they lean towards each other, slouching and straightening their hair.

Some of Degas's paintings portray a tender world of women; some show ominous figures lurking in the periphery. Men in dark suits and top hats creep into the wings, their faces obscured by shadows. Ballet masters, always men, dominate the classroom, wooden sticks in hand.

In Degas's time, the Paris Opera was a center of prepubescent prostitution. Wealthy subscribers - known as abonnés - bought the right to mingle with dancers backstage and hang out in the wings during live performances. Opened in 1875, the architecture of the Palais Garnier was designed to facilitate meetings between the dancers and their sponsors: the ornate foyer de la danse functioned as both a rehearsal studio and a backdrop for rendezvous.

"Backstage at the opera was the veritable fiefdom of rich men, who treated the ballet dancers as a kind of game reserve," historian Robert Herbert once noted. The three boxes with the best view of the stage were reserved for the emperor, who was "not at all shy about using his perch to explore beautiful women." Young dancers - trained in seduction as well as ballet - were thought to make excellent mistresses. "Be charming and sensual," 19th-century ballet master Auguste Vestris advised his students. "The box, the orchestra and the seat holders would like to carry you to bed."

This system was so entrenched that it was described as an attraction in a city guide. "As long as you are a financier, a yellow glove investor, a stockbroker... as long as you are something like a dancer's uncle or her protector... then the portals [to the Opera's backstage world] be open to you," wrote Eugène Chapus in Le Sport à Paris.

During Degas' time, the hemline of the tutu - once a modest calf-length garment - became shorter. The dancers of 19th-century Paris were valued less for their artistry than for the tantalizing sight of their exposed legs and arms: a rare occurrence outside the demimonde. Some ballets were full-length entertainment, but dancers more often performed in short divertissements embedded in operas. These interludes were usually postponed until Act II, giving the subscribers and their ballerina dates time to complete the dinner. (When Richard Wagner bucked this convention and dared to include a ballet in the first act of Tannhäuser (1845), angry members of the Jockey Club whistled their disapproval.)

There is a cruelty in Degas's portrayal of the ballet world. In his photographs, women could only be mothers and dancers; men were authority figures and wealthy patrons, never equals.

The teenage dancers who came to Degas' studio were often young girls from the Paris Opera Ballet school, derisively known as petits rats - a nickname given by the French poet Théophile Gautier, who wrote of their "gnawing and destructive tendencies". Dancers in training could be chosen for their appearance as well as their talent, and often came from desperate families. Matriculation records from 1850 show that about half of the students had no known father; the mothers worked as low-paid laundresses or janitors and would have liked an extra income. Many mothers, instead of protecting their daughters, encouraged them to flirt with potential customers; and in Degas's paintings the mothers often appear as darkly dressed and menacing as the voluptuous male spectators.

But seen from another angle, there is dignity in Degas' portrayal. Sometimes he painted étoiles, but more often he hired anonymous students to pose in his studio and elevate them to leading roles in his art. "It seems that Degas took a quiet pleasure in giving the dancer-in-training a prominent place, something she would probably not have enjoyed on this date," write Degas scholars Richard Kendall and Jill Devonyar in Degas and the Ballet: Picturing Movement. He sometimes included their names in his early ballet works. For example, on an 1880 charcoal sketch of a dancer raising her leg in a à la second battement, the teenage model's name - "Melina" - is given as much space as Degas's own signature.

But just as often - and especially in his later work - the women's faces are blurred. His focus shifted from the individual dancers and their identities to the hum of movement and light - swirling tutus, sweaty legs.

Perhaps Degas recognized something familiar in the strict discipline of the dancers. "It is essential to redo the same subject ten times, a hundred times," said the artist, describing his own approach to work. Like an intern at the Paris Opera repeating her endless pliés and tendus, Degas drew the same model over and over again, in slight variations on the same pose.

And like the dancers, he could be ruthlessly harsh in his own assessment of his art. He once confided to a friend that he wished he could buy back - and destroy - all his early work. When I read this anecdote, I thought of Susan Sontag's 1987 observation that "no performer is as self-critical as a dancer." Ballet dancers are trained to constantly check the mirror for mistakes and are notorious perfectionists, almost never satisfied with a performance.

Sexual exploitation is not as blatant in today's ballet world as it was in 19th century France; social norms have changed. Companies no longer sell access to dancers' dressing rooms or allow men to wander backstage during performances. Class dynamics have also changed. It costs more than £30,000 a year to study at the Royal Ballet School in London, and dancers' salaries are relatively low; ballet tends to attract children from affluent families.

Ballet is a prestigious art form today - but the ballerina is still a sex symbol. Many dancers supplement their income by making extra money as Instagram influencers or models. When I studied ballet in the mid-2000s, I was told to tilt my head to croisé devant as if I were "asking for a kiss."

Costumes are more revealing than ever; In the mid-20th century, George Balanchine's costume designer Karinska invented a tutu so short that it stood almost perpendicular, exposing the dancer's entire lower body. Subsequently, Balanchine abolished tutus altogether and only sent women on stage in tight-fitting tights. Depriving dancers of even a layer of tulle added to the pressure to maintain a perfect body.

While abuse may no longer be crudely advertised in guidebooks, it is now more discreet and covered by a code of confidentiality. Dancers are trained to fulfill a choreographer's vision and suppress their own impulses in favor of adaptation. As in 19th-century France, passivity can be rewarded.

Even now that ballet has been professionalized, power differentials persist. Girls and women still make up the majority of ballet students and corps dancers, while men are overrepresented in positions of authority. As recently as the 2020-2021 season, men choreographed 69 percent of the ballets programmed by the major American companies.

Competition for jobs is fierce, especially among women - and few are willing to risk a scandal. It is mainly whistleblowers and ex-dancers who dare to come forward with allegations of abuse. In 2013, Russian former dancer Anastasia Volochkova compared the Bolshoi to "a gigantic brothel," claiming that ballerinas were pressured to sleep with wealthy clients - claims dismissed as "rabble" by the company's general manager dismissed. In her 2021 memoir Swan Dive, soon-to-retire New York City Ballet soloist Georgina Pazcoguin alleged that a male colleague, Amar Ramasar, routinely pinched her nipples in class. (Ramasar denied the accusation.)

Degas's photographs remain beloved by dancers: from students who hang prints of The Dance Class (1874) on their bedroom walls to stars like Misty Copeland, who reenacted Degas' The Star (1878) for Harper's Bazaar. Perhaps they see something familiar in the danger on the sidelines and the girls' striving faces - a sisterhood that crosses the ages.

Discovering Degas is on view at the Burrell Collection, Glasgow, from Friday 30 September (burrellcollection.com); Alice Robb's latest book is Don't think, dear: about loving and leaving ballet (Oneworld, £10.99)