Recently I posted a recap of my Philosophy Now article critiquing Julian Jaynes’s “bicameral mind” theory. Marcel Kuijsten replies with a long scathing attack, on the Julian Jaynes Society website.*

I criticized, as historically wrong, Jaynes’s argument that societal upheavals around that time caused the changeover. Kuijsten doesn’t really rebut that, but says Jaynes was instead relying mainly on supposed evidence that the change did occur then, such as the “cognitive explosion” of Greek philosophy and the religious “Axial age” – which actually came somewhat later! – but this just begs the question of why the alleged dramatic transformation occurred, leaving Jaynes with no answer.

And if the Greek flourishing evidenced the onset of introspective consciousness, did the later Dark Age evidence its loss?

Really? Has he never met a fundamentalist Christian? “No need for gods” indeed!

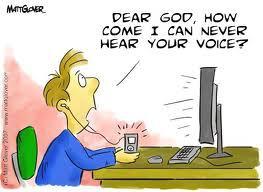

I have read intensively about ancient societies, and Kuijsten’s casting them as god-obsessed is very dubious. The idea of gods was a handy construct to explain the inexplicable, but people didn’t take it all that seriously. God plays a far bigger role in the lives of many religious believers today. Yet Kuijsten doesn’t suggest they’re bicameral.

Joseph Smith with his harem

He does cite some fairly modern people, like Mormonism’s founder Joseph Smith, hearing god voices, as supposed vestiges of bicameralism. Kuijsten seems to take such stories at face value. Smith (whose life I’ve studied) heard no voices; he was a con man who made it all up to gain wealth, power, and sex with lots of women. No doubt “god voices” were similarly useful for the ancient priests Kuijsten invokes.

He makes many other similar arguments that modern mental phenomenology evidences a past bicameralism; such as auditory hallucinations, which he says are quite common among normal people. Common (on occasion), perhaps; normal (if continual), no. Normal healthy people don’t constantly hear voices thinking they’re from gods; and mentally healthy ancient people likewise did not confuse their own thoughts with god voices.

My assumption that introspective consciousness was a very ancient biological adaptation is attacked as lacking evidence. The only alternative is woo-woo supernaturalism. And while Kuijsten says such consciousness could not have evolved without language sophistication, that certainly arrived long before 1000 BC. Kuijsten himself elsewhere puts it around 50,000 BC!

I am labeled “oblivious” to dozens of brain imaging studies supposedly validating Jaynes’s model. Well, I’m no neuroscientist; but I daresay no 3,000-year-old people have had their brains imaged.

Kuijsten (like one blog commenter) also emphasizes that much mental activity and behavior is unconscious or not fully present; and the concept of self can vary among different people and cultures. All true, but hardly suggestive that even the dullest normal modern human lacks a sense of self. The same would be true of our ancestors. And while just what a sense of self really means has long vexed philosophers, we all know what the concept refers to. There’s no convincing reason to imagine people before 1000 BC didn’t have it, and believed their own thoughts were voices of gods. They were not so stupid.

My poet wife points me to the work of Enheduanna, c. 2300 BC, the first writer to sign her name. Here’s a sample. Read this and try to tell me she lacked a self.

Kuijsten’s final line notes the tendency “to only seek evidence that confirms are (sic) existing beliefs.” His own article is a prime example.

* I have (so far) been denied access to respond on that website itself.