* * * * *

Just the other day The New York Times’ John Markoff published an article on recent and apparently dramatic success in artificial intelligence: Scientists See Promise in Deep-Learning Programs. I skimmed the article—which said almost nothing about the techniques of this deep-learning—and wondered whether or not we’re being set-up for another fall. Markoff mentions the so-called “AI winter” of the mid-1980s that froze out entrepreneurial dreams of riches through practical AI when the practical proved impossible. He doesn’t mention that something similar happened to machine translation and computational linguistics in the early 1960s when Federal funding disappeared.

Stalking the Wild Teleome

So, with wonder in hand, I went over to Changizi and asked: “What do you think, boom or bust?” Mark pulled out his post: What Should We Unravel Next, After the Genome? Answer: The Teleome. He sets the stage:

Imagine that you find some mysterious device under your bed. What’s your next thought? It’s to wonder what the device does. Could it be a hand vacuum, a kid toy? …a bomb? Notice that your first thought does not concern how the device works. It’s premature to get to the “how it works” without having figured out the “what it does”. Obviously!On the one hand, yes, sure, I agree. On the other hand, just a minute there. As you know I study literary texts, among other complex cultural objects such as movies, music, and graffiti. Not so long ago I found myself hip deep in nonsense about the adaptive purpose of art: it’s all about mating, no it’s about useful stories, no no no it’s about figuring out what to do with hyperactive intelligence, and so on. That is, they seem to be taking Changizi’s advice and are trying to figure out what it’s doing when the brain’s pumping out art and such. They’re looking for purpose, for what the design is supposed to accomplish.

In much of the biological and brain sciences, however, there appears to be something of an inversion to this. In many scientific circles questions about “what it does” are deemed intrinsically unscientific or meaningless, and explanations in that domain are necessarily “just so” stories rather than science. Only questions concerning the biological mechanisms — i.e., concerning “how it works” — are truly kosher. And this attitude is reflected in funding priorities: ”how” funding dominates the “what it’s for” funding by a mile.

On the other hand, though I have in fact given some thought to the question of just why, biologically, we make art (e.g. Emotion Recollected in Tranquility), I’ve been more compelled by the question How does it work? So I seem to be taking the wrong side of Changizi’s argument. Changizi argues we’re not going to figure out how it works until we know what it’s trying to do:

We need a “teleome,” the ultimate catalog of an animal’s what-it-does-es. The teleome is something along the lines of the set of all the capabilities our brains and bodies were selected to carry out. It is our set of powers, or the set of things we can do, or our function list.Now, I rather doubt that Changizi would be enlightened if someone told him that, among the many powers of human brains and bodies, are the powers to make poems, music, and images. I mean, he already knows that, just as he knows that human brains and bodies fight wars, negotiate treaties, and even, on rare occasions, go boldly where no man has gone before. These proposals are chosen from the wrong conceptual universe; they don’t quite mesh with the conceptual materials of the cognitive, behavioral, and neurosciences.

A bit later in his post Changizi more or less addresses this issue: “it is not yet clear what [the teleome] would even look like. Surely it would not simply be a list. Instead, it would probably be a hierarchically tiered structure of some kind, with powers built out of sub-powers, and so on.”

Yep.

Hierarchically tiered structure.

Yep.

Powers built out of subpowers.

Check.

Describing, for example, a poem

So what’s this have to do with the humanities and poems and things like that?

Well, let me assert that, to a first approximation, writing a poem or telling a good story engages a wide range of human capabilities in an integrated fashion. Keith Oatley argues that literary texts are simulations, in the computer science sense of the term, of living life—and a half century ago Susan Langer (Feeling and Form) talked of the arts as providing virtual (her word) experience. Whatever the mind’s mechanisms are, a whole bunch of them are in use when making or comprehending art.

That’s not a trivial observation, though just how one capitalizes on it is another matter, which I’ll get to in a moment. Experimental psychology necessarily observes highly circumscribed behaviors, pressing buttons in response to carefully crafted visual or auditory stimuli and such. But you aren’t going to figure out how the whole mechanism works, as a whole, in that way. But there’s really no way to make closely controlled and highly detailed observations of how people live their lives.

So, how’re you going to figure THAT out? What’s the teleome for that, Jack?

I suggest that we use artistic activity as a proxy for that. We CAN study novels and poems, paintings and sculptures, songs and symphonies, and so forth. Not only can we study the works themselves, we can study people comprehending them, we can even image brain activity while they’re doing. We can do, and are doing, all of that.

It’s here that I see a role for the rich and precise description of, for example, poems, descriptions of a sort that really haven’t been done consistently on a extensive scale. Now, a description of a poem certainly IS NOT a description of the mechanism that built or comprehends that poem. Not at all. But it does place constraints on proposals for such a mechanism, providing, of course, that the description is couched in terms that are commensurate with those of the “tinker-toys” from which one builds mechanisms.

At the same time proper descriptions also provide, in a way, an answer to the question: What does it do? What does it do? you ask. Why it builds things like THAT, where that indicates, not the poem directly, but the proper description of the poem. That description, by its nature as a description, reveals something about the poem’s design.

As a small example, consider this:

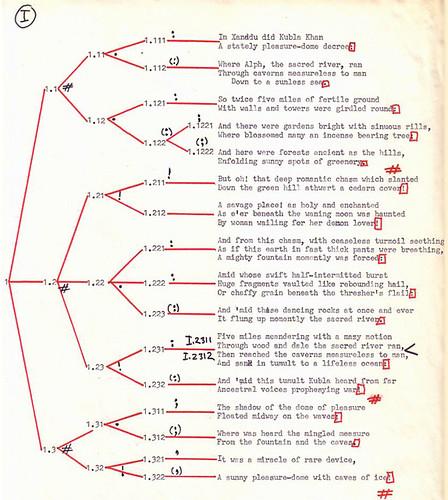

On the right you see the first 36 lines of Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan.” On the left you see a description, in the form of a tree, of how lines are hierarchically combined into larger structural units. Any proposal for a mechanism by which this poem is comprehended is going to have to be able to accommodate that structure, whatever “accommodate” means in this case, which is not at all obvious.

Notice that the overall structure of those 36 lines consists of three groups of lines. The middle of those three, in turn, consists of three groups of lines, and the middle of THAT, in turn, consists of three groups of lines. The overall impression is that of one of those Russian dolls, where a doll is embedded within a doll, within a doll, and so forth.

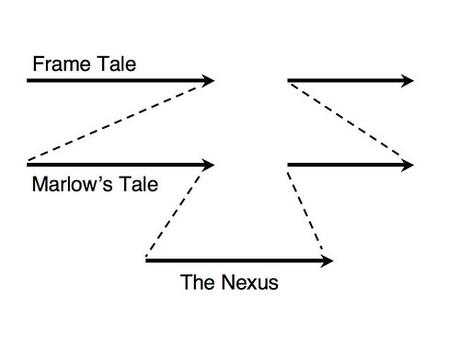

Now look at this somewhat simpler diagrams, which depicts the overall narrative structure of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness:

The stretch of text I’m calling the nexus is, I argue in this post and in this working paper, the structural center of the story. That story thus is similar to “Kubla Khan” in that it has a unit, the nexus, within a unit, Marlow’s tale, within the overall narrative as presented through the frame tale. Yet it’s otherwise a very different chunk of language.

The stretch of text I’m calling the nexus is, I argue in this post and in this working paper, the structural center of the story. That story thus is similar to “Kubla Khan” in that it has a unit, the nexus, within a unit, Marlow’s tale, within the overall narrative as presented through the frame tale. Yet it’s otherwise a very different chunk of language.

The Heart of Darkness is a prose narrative of some 38,000 words while “Kubla Khan” is a lyric poem of 54 lines and 352 words. That these two very different chunks of language, both skillfully wrought by masterful craftsmen, should share a similar structural feature is, well, it’s interesting. And any account of the mind’s mechanisms is going to have to accommodate both of these texts, and many others besides.

Now, that’s only one aspect of what’s entailed in describing texts. I’ve got much more to say about “Kubla Khan” in this rather longish paper, “Kubla Khan” and the Embodied Mind; and a more informal document presents quite a bit of descriptive detail about Conrad’s text (Heart of Darkness: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis on Several Scales). Nor do those papers exhaust the descriptive work that can be done with those texts, for they are very complicated objects.

Rich Descriptions as Proxies

As are most works of art. As a practical matter, we’ll want to describe some in considerable detail, while others may not be described beyond what’s necessary to classify them in some as-yet non-existent scheme. What’s important are the terms of the classification. We need to use terms commensurate with those in the tool kits from which explanatory models are to be constructed. And then we need to make proper descriptions.

While I do not regard these matters as obvious, I don’t think that they’re intractable either. I note that it took biologists awhile to figure out how to describe life forms and it was only in the 20th century that it became possible even to “see” the molecular building blocks of living organisms. If humanists want to undertake the task of rich description, we can do so.

I say humanists not merely because the study of poems and such falls within the traditional purview of the humanities, but because you cannot create accurate descriptions unless you have a feel for the phenomena. And the only way to acquire a feel for the phenomena is through total immersion. You cannot get there through one or two examples. It takes hundreds of examples, some considered in considerable detail, others more casually. But, in one way or the other, hundreds or even thousands examples must be taken in review.

Returning to Changizi’s argument, my overall point is that such descriptions can be taken as useful proxies for the teleome he’s urging us to construct. What does the brain do? It builds things like THAT and THAT and THAT and THAT and so forth. Each of those THATs is a proper description of some art work (or other suitably rich and complex artifact).

The mechanisms we seek certainly aren’t simply going to fall out of those descriptions. But without a large collection of such descriptions we’re working blind. They may not be Changizi’s teleome, but they’ll help us to construct it.