Book Review by Val Hewson:

‘My dear mother,’ Imhotep looked at her in horror. ‘This is not a jest.’

‘All life is a jest, Imhotep – and it is death who laughs last. … it is a question only of whose death will come tomorrow.’ (Death, p. 202.)

Agatha Christie (1890-1976) seems now almost a writer of historical crime fiction. We watch, and watch again, all those meticulously recreated country estates, townhouses and, yes, trains, with Poirot, Miss Marple, and all those victims, suspects and murderers. When we read the novels, we effortlessly summon up the images of a world long gone. But Christie of course was writing not about the past but about the world she knew. Her first novel was published over a century ago and the last in the year she died, already half a century ago. Only one of her 66 full-length novels is set in her (and our) past: Death Comes as the End, published in the USA in 1944 and in the UK in 1945.

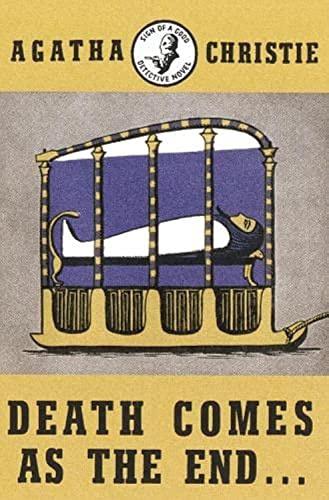

First edition Crime Club 1945.

First edition Crime Club 1945.

Death takes us back 4,000 years to Ancient Egypt, to a country estate near Thebes, which belongs to a prosperous family. There’s the patriarch, Imhotep, who is losing control, and his mother, Esa, physically weak but mentally sharp. He has two adult sons, plodding Yahmose and rash Sobek, and their scolding wives, all ambitious. Another son, Ipy, struts around, cocksure but still a boy. Imhotep’s daughter, Renisenb, has recently returned home, grieving for her dead husband. There are two outsiders: a poor relation, Henet, who spies and tells tales; and Hori, the estate manager, who worries over what he witnesses.

There are tensions in the family, but everyone rubs along well enough until Imhotep brings home a concubine. He introduces her as ‘Nofret, whom you shall love for my sake’. Well, yes. Nofret ‘stood there beside him, her head flung back, her eyes narrowed, young, arrogant and beautiful. Renisenb thought, with a shock of surprise: ‘But she’s quite young – perhaps not as old as I am.’ (Death, p. 33.) All those tensions promptly explode, and quarrels, fights, betrayals and murder result.

This should all sound familiar. These characters and their predicament are found throughout Christie’s work. ‘Both place and time are incidental to the story. Any other place at any other time would have served as well’, she writes (Death, p. 1). The setting of ancient Egypt comes as a surprise, but is easily explained. Christie was married to Max Mallowan (1904-1978), a noted archaeologist. She was genuinely interested in his work, and on digs worked as part of the team, recording and photographing finds. She had already written novels set in Iraq, Syria and Egypt, some with an archaeological background: Murder in Mesopotamia (1936), Death on the Nile (1937), Appointment with Death (1938) and (as Mary Westmacott) Absent in the Spring (1944). In 1946, as Agatha Christie Mallowan, she published Come, Tell Me How You Live, about her experiences of archeology.

Ancient history was therefore familiar territory. It seems that she was prompted to write Death (and earlier, in 1937, a play, Akhnaton) by a family friend, the Egyptologist Stephen Glanville (1900-1956). He gave her an idea for a plot when he showed her complaining letters written by an ancient Egyptian to his family. Just so does Imhotep write to his family.

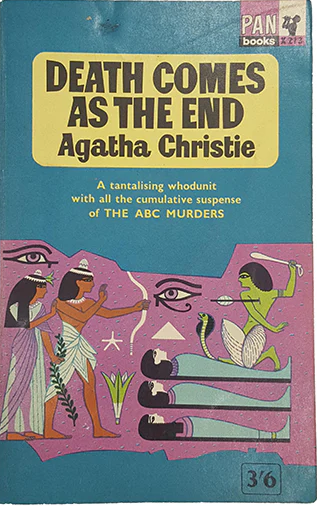

Pan paperback 1964.

Pan paperback 1964.

The setting of Death is one of the best things in it: dry heat and bright light, rich earth and harsh rock, the blue Nile on the horizon, a villa with cool porches and gardens. Imhotep and his family have a good life. Christie is carefully sparing of detail and presumably got information from Stephen Glanville. Lucy Worsley, in her 2022 biography, Agatha Christie, notes that Death was critiqued in archaeological circles (p. 273). Perhaps so, but the book easily convinces the non-expert looking for entertainment.

Christie makes much of religion, ritual and superstition. Renisenb, for example, walks where others have walked before her, only to meet their deaths. Did they see a malevolent spirit as they looked behind them? Is ‘doom overtaking her’ now? (Death, p. 250.) Imhotep turns to the local priests who help him write a letter to his long dead wife, Ashayet. ‘She was a woman of influential family. She can invoke powerful interests in the Land of the Dead, who can intervene on your behalf …’. (Death, p. 151.) There are plenty of funerals too, and Christie has fun here. There are the brine baths in which corpses are steeped; and at one point the demand for bandages finds Henet having to cut up fine linen sheets. Worst of all, there are the embalmers.

‘Ipi and Montu are, of course, expensive embalmers,’ went on Imhotep. ‘These canopic jars, for instance, seem to me unduly costly. There is really no need for such extravagance. … It would have come much cheaper to go to somebody less well known.’ (Death, p. 100.)

As the body count rises, Esa says: ‘All this must be a blessing to Ipi and Montu – the firm must be doing exceptionally well. … They should give us a cut rate price for quantity!’ (Death, p. 202.)

Death’s characters are rather less convincing than the world in which they exist. Characters like aging Imhotep, obedient Yahmose and Henet the snoop are types rather than fully rounded. This is a book without a detective, amateur or professional, to review events and uncover the true story, although some of the family do try to puzzle it out.

This brings us to Renisenb, Imhotep’s daughter who has come home after her husband’s death. We see much of the action through her eyes. She knows her family well: ‘[Hearing her brothers argue] gave her suddenly a feeling of security … She was home again.’(Death, p. 5.) At first, she thinks – wants – everything as it was. ‘Nothing changes here,’ said Renisenb with confidence.’ (Death, p. 16.) And yet, after eight years away, she sees change too.

She thought of [Imhotep] as rather a splendid being, tyrannical, often fussy, exhorting everybody right and left, and sometimes provoking her to quiet inward laughter, but nevertheless a personage. But this small, stout, elderly man, looking so full of his own importance and yet somehow failing to impress – what was wrong with her? (Death, p. 32.)

Renisenb can be perceptive, but she cannot think clearly. She is superstitious: ‘Hori, it must be magic! Evil magic, the spell of an evil spirit.’ (Death, p. 228.) She believes people, whether she has reason to trust them or not. ‘I was to wait until I got you alone to say this – and no-one was to overhear.’ (Death, p. 246.) This is all part of Christie’s effort to distract us, but Renisenb is surely too feeble for us to take her seriously.

Christie keeps us off balance, as always. Death comes so fast and often that there’s barely time to guess whodunnit before it happens again. In the end the truth is revealed in a very business-like way. She said in Agatha Christie: An Autobiography (1977) that Stephen Glanville persuaded her to change the ending – she doesn’t say how – and that she regretted this. Did Christie feel outside of her comfort zone and want to be done with the book? Or perhaps she was just weary. It was wartime, and for a long time she lived alone in London, working as a hospital dispenser and writing in her off-duty hours. Her output was tremendous – publishing about ten novels, including some of her best; and the last Poirot and Miss Marple stories written and locked away for posthumous publication. In a way, of course, none of this matters much. Looking to be entertained, we settle into Death easily and are carried along by the pace of events. Death is not one of Christie’s best novels by any means, but it is an enjoyable puzzle.

Historical crime fiction is hugely popular today. Many of the stories are set in the Golden Age of Crime, the 1920s and 1930s, when Christie was arguably at the top of her game, developing the detective story in all sorts of ways. (She even appears as a detective herself, in books by Alison Joseph, Andrew Wilson and others.) As Lucy Worsley and others have noted, Death is an early example of historical crime fiction, and reminds us again just how innovative Christie was.

Note: All page references are from the HarperCollins Masterpiece Ed ebook of Death Comes as the End (2010).

Green Penguin, 1953.

Green Penguin, 1953.