– Who’s coming after you?

– My past. Every dark, miserable day of it.

I guess that short exchange, coming near the end of the movie, sums up much of what Dawn at Socorro (1954) is all about. It’s a classic 50s western scenario, the hunger for a fresh start, a chance to slay the demons of one’s past once and for all. In the case of this film there’s the added interest of the disguised Earp/Holliday elements in the story, although this aspect is really only peripheral, and I think it’s no bad thing the names are changed and some of the events portrayed are used primarily as an inspiration – it allows the theme to develop without weighing it down with unnecessary historical baggage.

The story opens with a reminiscence, the words of an old man drawing us back into a past he experienced and into the lives of people he was once intimate with. Our point of entry comes in a cheap saloon, one of those basic drinking spots with low ceilings and lit by guttering lamps. The Ferris clan arrives en masse, planning to pick up the youngest member, Buddy (Skip Homeier), and head back to their ranch. But Buddy’s a hot-blooded guy, at that stage in life where he needs to show off in public how much of a man he is. Reluctantly, his kin leave him to his own devices, but still under the watchful eye of gunman Jimmy Rapp (Alex Nicol). The back room is occupied by the Ferris’ mortal enemies, Marshal McNair (James Millican) and ailing gambler Brett Wade (Rory Calhoun), and it’s only a matter of time before Buddy talks himself into a fight, one which will leave him dead and bring the feud between his family and McNair and Wade to a head. What we’re looking at here is a fictional account of the build up to the confrontation between the Clantons and Earps. It culminates in what is essentially the gunfight at the OK Corral in all but name. And the upshot of the killings is that the Holliday figure, Wade, is convinced of the folly of his lifestyle up to this point. He resolves to make a change, to get out of the territory and do something about his weakening health. Sharing a stage to Socorro with a bitter and self-loathing Rapp, he makes the acquaintance of fellow passenger, Rannah Hayes (Piper Laurie). Unknown to him, Rannah has been disowned by a father who believes the worst of her, and chooses to believe her lie that she’s on her way to meet her future husband. The truth is though that Rannah is going to become a saloon girl, working for Dick Braden (David Brian), a gambler whom Wade has clashed with before. It’s the realization of what is actually happening that leads Wade to put his plans to move on to Colorado on hold, to try to regain something of his youthful promise, to halt the waste and do something of worth before it’s too late.

There have been plenty of positive words about George Sherman on this site before, and Dawn at Socorro is another example of quality work from the director. The opening twenty minutes lays the groundwork for the Ferris (Clanton) and McNair (Earp) feud and the subsequent gunfight. The lengthy passage in the saloon, where the character dynamics are clearly defined, is beautifully shot and loaded with atmosphere. Sherman made good use of close-ups throughout the film, but these early scenes see them employed especially effectively. Although this is largely a town based, and therefore interior heavy, film, there is also some nice location work during the eventful stagecoach trip to Socorro. Also impressive is the shooting and composition of the key duel late in proceedings between Wade and Rapp – at the vital moment the camera is positioned high above both protagonists as they face off on the deserted Socorro street. The unusual angle chosen assigns the viewer the role of dispassionate observer gazing down on two regretful men, their individuality diluted by the distance as they become merely a pair of gunfighters on a dusty thoroughfare, their actions mirroring each other and the fatal shots appearing as simultaneous bursts of smoke.

So many westerns have concerned themselves with the dogged pursuit of individuals by the sins of their past, and the salvation, redemption or personal understanding or acceptance which grows out of this. It can be seen as a general western motif I suppose, but in the 50s in particular almost every genre entry of worth features these themes. I may be way off base here (so feel free to pull me up on this if it appears I’m mistaken) but I’m now of the opinion that this phenomenon has its roots in the post-war climate of coming to terms with the events of the past. The world had only recently recovered some kind of equilibrium after years of violence and uncertainty. Those war years represented a loss of innocence for a generation, a time of intense emotional and physical challenge, so it seems natural that the modern art form of the cinema should try to address that. I can imagine audiences of the time would have identified with tales of people struggling to escape the horrors of a violent past and by doing so perhaps regain at least a shred of their former innocence.

The Brett Wade character is very obviously based on Doc Holliday, featuring all the familiar traits which have become associated with Wyatt Earp’s ally in many films over the years. It always provides a strong role for whoever plays it and Rory Calhoun is given plenty to get his teeth into. The combination of swaggering bravado on the outside and corrosive introspection in private automatically rounds out the Wade figure – there’s that essential loneliness and otherness that the more intriguing western characters tend to display. But there’s solidarity too as most of the main players in the drama are consumed with a desire to get back to an imagined idyll, a simpler existence they still recall yet have misplaced through time. When Mara Corday’s disillusioned saloon girl wistfully inquires “How do you turn back the clock?” you know that nobody will be able to hand her a satisfactory answer.

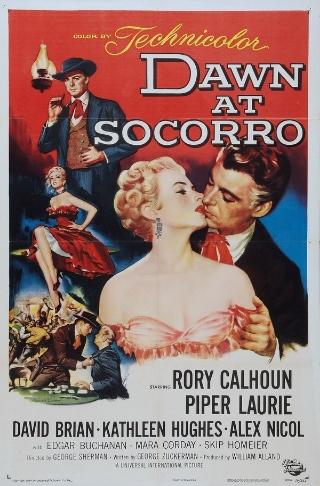

Piper Laurie does some good work too as the young woman rejected by her father and facing a highly uncertain future, trying to convince herself of her suitability for the new life she’s prepared to take on while still dreaming of the one she’s been deprived of. And then we have Alex Nicol, an ever interesting actor, who plays a Johnny Ringo type. Nicol is embittered from the moment we first see him, drinking heavily to deaden some half-defined inner pain, and later overcome and ultimately destroyed by a sense of guilt and inadequacy – I find him the most fascinating figure in the whole movie. The real villain is played by David Brian, a man whose career started off very strong but seemed to stutter soon after. He’s suave, slippery and deadly, a guy with no redeeming features but an excellent foil for the hero. The supporting cast is full of fine actors and it’s pity there wasn’t more for some of them to do: James Millican Lee Van Cleef, Skip Homeier, Kathleen Hughes, Edgar Buchanan and Roy Roberts being the most notable of the long list of familiar faces.

The last few years have seen more and more frequently neglected films from this era getting releases, and Dawn at Socorro is now reasonably easy to get hold of. There was a box set of Universal-International westerns (Horizons West) put out a few years ago and this title was included. There’s also a Spanish DVD, which I have, and the film seems to be available to view on YT as well. I’d imagine a 1954 movie would be shot with some widescreen process in mind – IMDb suggests 2.00:1 – but my Spanish copy presents it full frame, as can be seen from the screen captures above. That aside, the transfer is generally strong, with the Technicolor looking vibrant and the image sharp. There are a few incidences of print damage, but nothing all that distracting. Dawn at Socorro is a western I like very much, with good work by Calhoun and director Sherman. The whole thing has a handsome look, is pacy and well scripted with characterization developed as the story progresses rather than through tiresome and unnatural exposition. One to look out for if you haven’t yet seen it, or to view again if you’re already acquainted.