As regular readers of this blog will know, I have been following the Month of Letters February challenge for the past few years, I think since its first year. I missed last year, but I am back on course for 2018. In honor of Month of Letters, I usually try to write a letter themed post at this time, and so here is this February’s offering. I also hope to give an update on my letter writing progress too as the month goes on.

My letter themed post this time features one of my all-time favorite writers, Daphne du Maurier in correspondence with a fellow writer, Oriel Malet. The collection, edited by Oriel Malet is entitled Letters from Menabilly: Portrait of a Friendship (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1993). I have had this collection for some while and I don’t think I have ever got around to reading it properly. It was published in the same years as Margaret Forster’s biography of Daphne du Maurier, whom Oriel Malet credits in her acknowledgments. I bought the biography the same year it came out, but I think Letters from Menabilly came to me some years later as a second-hand bargain. The letters interspersed with Malet’s commentary chart the course of a thirty-year friendship between the women and their families beginning with their chance meeting in the mid-1950s.

My letter themed post this time features one of my all-time favorite writers, Daphne du Maurier in correspondence with a fellow writer, Oriel Malet. The collection, edited by Oriel Malet is entitled Letters from Menabilly: Portrait of a Friendship (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1993). I have had this collection for some while and I don’t think I have ever got around to reading it properly. It was published in the same years as Margaret Forster’s biography of Daphne du Maurier, whom Oriel Malet credits in her acknowledgments. I bought the biography the same year it came out, but I think Letters from Menabilly came to me some years later as a second-hand bargain. The letters interspersed with Malet’s commentary chart the course of a thirty-year friendship between the women and their families beginning with their chance meeting in the mid-1950s.

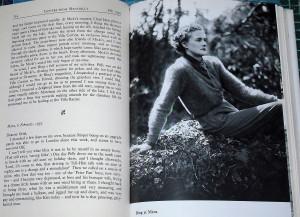

Oriel Malet begins the book by talking about how, when and where she and Daphne du Maurier first met and how their relationship developed. She was still a young writer at this point whereas du Maurier was very successful and well-known. Malet at this point had heard of du Maurier but not read any of her books. They shared an American publisher, Doubleday, and first met at a London party hosted by the publisher’s wife Ellen Doubleday. They had shared a mutual dislike of social gatherings and being forced to meet new people, but when they found themselves waiting outside the Doubleday hotel suite for the hostess to arrive, they struck up an unforced conversation. Neither woman introduced herself and it wasn’t until the party began that Oriel Malet realised to whom she had been speaking. She described Daphne rather poetically thus, ‘she reminded me of a figurehead at the prow of a ship; alert, poised, looking into the distance yet perhaps laughing inwardly and no more at ease in so worldly as setting than I was myself’. If you look at this photo from the book you can see what she meant. They sneaked away from the party together and talked while Daphne packed for her return to trip to Cornwall. And the rest as they say, was history. The letters cover many topics and events in the women’s lives, but I just want to focus on one of the conversational threads for this blog post.

Taken from my copy of Letters from Menabilly

" data-orig-size="2401,1733" sizes="(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px" data-image-title="Portrait of Daphne du Maurier" data-orig-file="https://talesfromthelandingbookshelves.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/portrait-of-daphne.jpg" data-image-meta="{"aperture":"3.4","credit":"","camera":"FinePix J10","caption":"","created_timestamp":"1517485484","copyright":"","focal_length":"9","iso":"200","shutter_speed":"0.016666666666667","title":"","orientation":"1"}" width="300" data-medium-file="https://talesfromthelandingbookshelves.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/portrait-of-daphne.jpg?w=300&h;=217" data-permalink="https://talesfromthelandingbookshelves.com/2018/02/16/daphne-du-maurier-oriel-malet/portrait-of-daphne/" alt="Portrait of Daphne du Maurier" height="217" srcset="https://talesfromthelandingbookshelves.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/portrait-of-daphne.jpg?w=300&h;=217 300w, https://talesfromthelandingbookshelves.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/portrait-of-daphne.jpg?w=600&h;=434 600w, https://talesfromthelandingbookshelves.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/portrait-of-daphne.jpg?w=150&h;=108 150w" class="alignright size-medium wp-image-3925" data-large-file="https://talesfromthelandingbookshelves.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/portrait-of-daphne.jpg?w=640" />Literary advice

I was particularly interested in Daphne du Maurier’s generosity in giving advice to the younger writer. Over the course of the years the two women discussed writers (both of them were Katherine Mansfield fans) and writing in both general and specific terms. In one of the early letters in the collection, du Maurier gives Malet advice on a book that she is working on, saying ‘You don’t have to have a ‘plot’; it sounds like Guy Fawkes in his old cloak, creeping with a lantern’. The imagery is amusing but she goes on to explain her point, elaborating thus, ‘You don’t even have to have action (think of Proust). But you must have a real reason for it all, a reason for the things you want to say’. Eminently sensible advice from a seasoned professional. In a later letter after reading a draft of a short story, du Maurier urges Malet to consider its potential as a novel,

I read your story going up in the train, and was absorbed by it. I love the way you write, and the things you write about, but my criticism would be that this atmosphere and story are wasted on a short story – you should develop it into a novel … I think you have the potential material here for a lovely long and interesting book.

The letters and Oriel Malet’s memories of her visits to Menabilly also weave in the progress of du Maurier’s own work. On one such visit, Malet recalls crossing a field and being afraid of a resident bull. Du Maurier was however more concerned with a flock of seagulls, remarking how frightening it would be ‘if all the birds in the world were to gang up together and attack us…..They could you know’. She was proved right in the disturbing short story ‘The Birds’ (from The Appletree, Gollancz, 1952) which was filmed by Alfred Hitchcock in 1963.

I was also intrigued by the importance of the Brontës’ early writing about the fictional world of Angria and Gondal. In du Maurier-speak, ‘to Gondal’ meant to pretend or to make-believe and the expression crops up several times during the course of the correspondence. In August 1963, Daphne wrote to Oriel,

If I pass a place I once lived (like at Hampstead), I often do a Gondal, whereby I go into it just as if it were still mine, and take my coat off, and somehow settle down, and then try to imagine the amaze surprise of the new owner coming in, and how one would behave in the Gondal just as if they were not there, and one was still in possession. …

Another thing I Gondal about, is supposing one suddenly went and rang at a person’s house, who was a Fan- …

Du Maurier was fascinated by Branwell Brontë and the book she wrote about him, the Infernal World of Branwell Brontë appears to have been simmering in the background for many years. She was very knowledgeable about the Brontë family and visited Haworth with Oriel after being asked to write a preface for a new edition of Wuthering Heights in 1954. Oriel later received a letter in which Daphne says the Macdonald Classics editor claimed that ‘he had never read anything before that gave him such a vivid and convincing impression of her [Emily’s] work and personality’. I was amused to note that the literary tone of this letter finished on a prosaic note however, mentioning a friend’s assertion that the Channel boats would go on strike as they were owned by British Railways. Daphne anxiously enquires of Oriel, ‘Do you think this is true?’ Clearly even best-selling writers have to be practical.

A note on the ‘in’ language in the letters

The first thing a reader notices in reading any collection of letters such as this, is that a private world is laid open for perusal. I would recommend not neglecting to read Oriel Malet’s helpful glossary of the du Maurier family’s expressions and nicknames before you start the letters, or you will be forever dodging back and forth to clarify the meaning of sentences, especially Malet took on some of these expressions and uses them in her reminisces. I found it strange to be grappling with family language because it did at times make me feel that I was an unwanted intruder into a private world. There is also the disconcerting feeling that it is all a bit childish for adults to be using what sometimes seemed like nursery language. For instance, Du Maurier refers to having a period as having a ‘Robert’ and ‘to wax’ meaning sex. On the other hand, her term ‘brewing’ for working on a story or plot makes perfect sense and conjures up a sense of the author intently and productively mulling over her characters and their actions.

Having said all of that, I found much to enjoy in the letters and the accompanying contextual passages. In fact, I am struggling to suppress an urge to re-read all of the Daphne du Maurier books I have ever read and to catch up on those I have mysteriously missed out reading to date. Another blog series methinks. Now on my mental TBR pile are books by Oriel Malet, as I must confess that I have never read any of her books.

I have also come across a post about Daphne and Oriel on a blog called Something Rhymed, which looks at female literary friendships.

Do drop me a line if you are a Du Maurier fan too!

Advertisements &b; &b;