Les liaisons dangereuses © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on canvas)

The winds of change bring not just cooling Autumn rain, but also new adventures: within a month I will be leaving warm, sleepy Australia for sparkling Vienna. I’ll be trading rough and ready Brisbane for a (the?) global cultural capital, whiling away my hours swooning over paintings at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, spending my evenings at the opera, and doing some Very Serious Painting over gold-leaf-flecked cakes and creamy coffee.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Having recently finished an ambitious book that links together art, neuroscience, psychology and Vienna, I am filled with confidence at a new aspect to my direction in life. Eric R Kandel’s The Age of Insight: The quest to understand the unconscious in art, mind and brain, from Vienna 1900 to the present talks intelligently to the reader, delving into current brain research and treating Freud’s brazenly novel ideas with honest admiration for what they set in motion. Plus, it is illustrated, with Klimt’s dreamy paintings and Kokoschka’s and Shiele’s charged paintings an optically pleasing counterbalance to brain diagrams and psychology flow-charts in the quest for the unconscious. The most striking thing about the book is that Kandel does not have to draw tenuous threads through these diverse fields: He simply situates them, historically, in one small city of two million people at the turn of the twentieth century, and unfolds a narrative of minds fertilising one another in an intellectually electric environment.

Austrian Parliament

That environment was cultivated in a very specific way. Vienna in 1900, argues Kandel (p. 499), ‘provided a social context—the university, coffeehouses, and salons—in which scientists and artists could readily exchange ideas.’ He cites Berta Zuckerkandl’s salon several times, and the luminaries she drew together, such as Klimt and Rodin. He writes extensively of the influence of Rokitansky in the Vienna Medical School, and the social connections struck up through the university between faculties. Vienna was a small place, something like Brisbane, and one can imagine the intimacy—in Brisbane there is a joke that there are only two degrees of separation between all of its inhabitants. Importantly, Kandel (p. 499) points out, scholars of the sciences and arts alike were united by a common interest: that of ‘unconscious mental processes,’ enabling a true dialog of benefit to all parties.

The dialog between art and brain science, Kandel (p. xvi) explains in his opening comments, is of mutual benefit because these two fields ‘represent two distinct perspectives on mind. Through science we know that all of our mental life arises from the activity of our brain. … Art, on the other hand, provides insight into the more fleeting, experiential qualities of mind, what a certain experience feels like.’ Where Freud could envision an idea of the unconscious that appeared to fit with his experience with his patients, and where brain science could seek to explain why these mysterious patterns exist, Kokoschka could, through his expressionist brushwork and symbolism, explain these concepts visually. Klimt’s art in particular drew on his knowledge of emerging science, and symbols of fertility permeate his paintings while visually describing sensuality in a very moving way. Kandel (p. 507) traces right back to da Vinci, who ‘used his newly gained knowledge of the human anatomy to depict the human form in a more compelling and accurate manner.

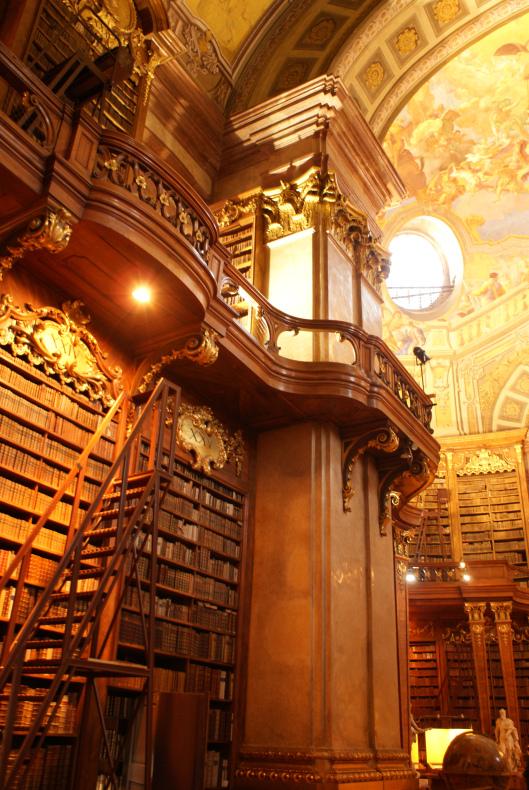

Bibliothek

All of this work chips away at the same problem from different angles, giving us different ways in, providing different insights, recording different aspects of our experience of our own minds. In a context where the work of these various fields can influence each other, new questions can arise; the cumulative body of work can grow in ways that each strain could not achieve independently. ‘It is quite likely,’ Kandel (p. 506) argues, ‘that finding new interactions between aspects of art and aspects of the science of perception and emotion will continue to enlighten both fields, and that in time those interactions may well have cumulative effects.’

Wiener Rathaus

Kandel (p. 501) asserts the need for a ‘third way, a set of explanatory bridges across the chasm between art and science.’ He envisions this third, conciliatory way as enabling discussion between heretofore restricted intellectual fields—a modern salon, centred around the universities (p. 505). It is at this point that I realize the immense value of the position I inhabit. A philosophy graduate, still tied up in the university, romantically partnered with a quantum physicist and able to move freely in these academic circles, I am also a painter, spending much of my time in the company of artists of an especially intellectual breed. While the Atelier exists outside of the university, it seeks to fulfill aspects of artistic study that I would venture that the fine arts in the university context in Australia cannot: pursuing excellence in practice and rigorous analytical thinking wholly tied up in that practice, not in conceptualising about social commentary or confusing the viewer through impenetrable artist statements and other trickery. Bringing these minds together—painters, philosophers and physicists—is about the noblest cause I can think of.

This work is already underway, in the coffee shops of Brisbane, in parties in old Queenslander houses, and in the old bomb factory warehouse that houses the Atelier. Ryan recently instituted a public lecture series at the Atelier, where intellectuals of all fields are invited to talk to artists in the spirit of collaboration. Jacques enthusiastically gave the first talk a couple of weeks ago, introducing current ideas in physics that might meld with ideas in art (you’ll be able to see his talk here soon). Ian Neill followed with a presentation on academicism in art. Rumour has it that Kari Sullivan will be sharing some linguistic observations pertaining to art, and that others have thoughts on the haphazard modern art education contrasted with the rigorous and ordered education of music, and the critical value of the peer review system sorely lacking in the visual arts where any amateur can demand respect. The topics are endless, the speakers willing, and the growing audience is stimulated.

Streets of Vienna

Most of all, I intend to continue to open my home—be it in Brisbane, Vienna, or anywhere else in this intellectually vibrant world—and share tasty food, abundant wine and fierce discussion with passionate thinkers in all fields. Consider this your invitation.

* Kandel, Eric R. 2012. The Age of Insight: The quest to understand the unconscious in art, mind and brain, from Vienna 1900 to the present. Random House: New York.

COMMENTS ( 1 )

posted on 16 August at 20:26

I am really happy to read this blog posts which includes lots of helpful facts, thanks for providing these data.