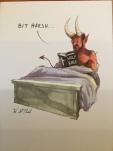

Having returned on Thursday evening from Sudan I left agin in the early hours of Saturday for Jena in Germany. This forms the real beginning of my sabbatical leave and gives the opportunity to read, write, think, meet people and, most importantly, gain a fresh perspective on life, the universe and everything. Somehow, being outside the UK, looking through a different lens and listening through a different language and culture, helps to make space for (what I think I want to call) newly refracted lines of looking, seeing and reflecting.

I am staying with a friend who is a professor in the Theologische Fakultät at the Friedrich-Schiller-Universität in Jena. This is where Hegel taught, and where Schiller met Goethe. Martin Luther spent time here, too. And it is the place where I have already come across thinkers I hadn’t encountered before.

Although it is good to be away from the UK for a time, the UK does not disappear. Nor does Brexit. Nor does the complex interplay of truth, power, victimhood and exploitation. If Brexit is bringing out the worst in us Brits, Germany is facing challenges with the Alternative für Deutschland and similar abuse of truth, fact and reality. Wherever we see this phenomenon – it is tempting just to shorthand it with the word ‘Trumpian’ – danger lies in waiting.

I recognize that this is a tenuous link, but Jesus’s friend Peter had to undergo a dreadful, world-shattering loss of personal illusion and confidence. After his denial of even knowing Jesus (just prior to the crucifixion), Peter watched his illusions of brave new world bleed real blood into the dirt of Calvary. He had to live through the emptiness of Saturday … only to find himself bewildered by the events of Easter Day. Subsequently, he was compelled to wrestle with the other friends of Jesus, with public authorities and political leaders, and with questions of how to lead and shape a church made up of people like and unlike himself. If he didn’t welcome power, he certainly had to face responsibility, costly choices, personality clashes and hard decisions that were bound to divide as well as unite.

So it is with politics. Power – to be exercised with responsibility and humility in the interests of the common good – is a hard business. Decisions will always disappoint someone. Leadership can be very lonely, even in the best of teams. But, it always exposes the truth about character. Our handling of power displays the reality of our character. If we merely resort to lies, game-playing and manipulation in the service of ideology, then the truth about our character, virtue and motivation will become evident quickly. And this, I suggest, is worrying. For, the evidence shows that I am usually the last person to see what everybody else sees quickly and clearly.

I can understand the ideological commitment to leave the EU. Questions of sovereignty, EU values and the bureaucratic machine in Brussels and Strasbourg make some sense to those who want some semblance of independence as a nation state. But, this commitment has to be earthed in relationships, processes, agreements, and future-orientated realities. Wanting to “get out” without paying attention to how to do it (and at what cost) is both ridiculous and dangerous. So, we see rich and powerful people leading the charge, making promises to which they will not be held, and knowing that they will not suffer at all if it all goes wrong for the UK. Poor people in challenging communities will pay the price – as they have been doing during the so-called ‘austerity years’ – and the powerful will exercise their power by maximising and protecting their own benefits … all while blaming everyone else for the ills that follow. We can’t all take our businesses to Singapore or Ireland.

Brexit will bring disillusionment – probably on all sides. Brexit won’t lead to economic or social nirvana for Leavers, and Remainers will continue to resist its consequences. Just as Faragistes never accepted the decision to join (what became) the EU, so many will immediately start the campaign to rejoin the EU one day. Brexit has not, could not and will not resolve the issue on these islands. But, it has exposed our deeper divisions (many of which have nothing whatsoever to do with Brexit or the EU), the poverty of our political culture (how can Labour still be six points behind the Tories in today’s polling?), the weakness of our national character, and our willingness to tell, hear and believe lies.

To return to Peter, his process of disillusionment was bitter, but necessary. Only by going through this and facing the truth about his own self could he grow to be the limestone leader he later became. In this sense, he bids us to do the same collectively: to grow up, lose our need to big ourselves up, see ourselves as we are seen from the outside, and value truth above illusion. The power – however damned – for this lies with us, and we can’t blame anyone else (Tories, Jeremy Corbyn, the EU) if we decline to use it.

Advertisements