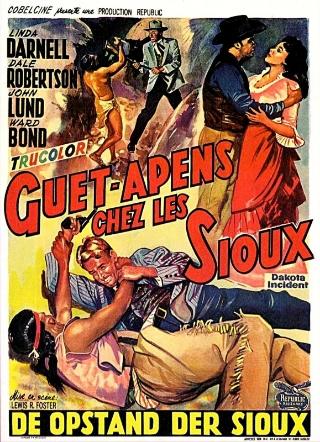

Republic Pictures was in business between 1935 and the late 50s, primarily concerned with producing B features or programmers the studio nevertheless produced its share of prestige vehicles too with the likes of John Ford, Orson Welles and Nicholas Ray making movies introduced by the famous eagle logo. Still, these were the exception rather than the norm, and Herbert J Yates’ studio generally contented itself with lower budgeted fare. Dakota Incident (1956) was one of he later offerings, made as Republic was beginning the slow wind down towards closure. One of the paradoxes frequently found in cheaply made movies is the way the financial constraints sometimes led to unusual results. And that’s certainly the case here; a well-worn central story drawing in a number of plot strands, not all of them successfully of course, and ending up as an intriguing study of the vagaries of human nature.

Dakota Incident starts out tense and sparse and continues in the same vein right up to its conclusion. The low-key score which plays over the credits, showing a trio of riders driving hard across barren country, sets the tone for what follows. These men are John Banner (Dale Robertson), Frank (Skip Homeier) and Largo (John Doucette), and it’s clear enough they’re running away from something or someone. The fact is they’re outlaws, making off with the proceeds of their latest robbery, and each distrustful of the other. Banner seems to be the leader, but his authority is suffered rather than accepted amicably. The lie of honor among thieves is quickly exposed as both Frank and Largo conspire to shoot down Banner, the latter actually doing so, before riding away with his share of the money. However, the victim isn’t really hurt, only playing possum, and sets off in pursuit of his duplicitous friends. He’ll track them down in a soon-to-be ghost town, a frontier settlement shrinking and dying under the constant threat of Indian attack. While Banner is settling scores others are preparing to leave town when the next stagecoach arrives. This section of the film, a reasonably lengthy one, establishes the identities of the main characters, and helps define the nature of their interconnected relationships. There’s a verbose senator from the east (Ward Bond), a cool and poised showgirl (Linda Darnell) and her mandolin-strumming minstrel companion (Regis Toomey), and a mysteriously taciturn gentleman (John Lund). All these people will board the stage bound for Laramie, all keen to leave their current location behind and all searching for something at the end of the line. What is sought becomes apparent as the journey gets underway, but what they actually find, holed up in a dry river course after an ambush, may not necessarily be the same.

Stories such as Dakota Incident concern themselves with the gradual stripping away of the layers of civilization with which we cloak ourselves, the shift of location from town to wilderness often being implemented as a visual signifier of the process. As soon as the stagecoach moves out into the desert the true characters which have only been superficially explored beforehand become more apparent. The most overt example of this is the way the attitudes to the Indian threat are articulated. It’s the senator who consistently tries to express sympathy and understanding for the native point of view, something which meets with increasing hostility and belligerence from the other passengers as the danger grows more intense. As such, the redemptive aspect (which must necessarily be present in almost any western of the period) applies much less to the senator than it does to the others. One could say that the senator’s journey is one of vindication while his fellow passengers are on the path to redemption. Banner experiences this on two fronts: the final erosion of his racial prejudice going hand in hand with a form of reconciliation with, and arguably atonement for, his criminal past and the consequences that has had for those around him.

Dakota Incident was directed by Lewis R Foster, a man whose career I’m not all that familiar with, although I do have a copy of another of his movies, Crashout, in my to-watch pile. While the town based section of the film has its moments, Foster does much better work when he takes things outside – the brief opening and then the long siege in the desert. The script, by Frederick Louis Fox, concentrates on the pressures the various characters come under and how they react to them. That siege in the dry riverbed has the result of turning the picture into a kind of claustrophobic chamber piece, the cast now limited to the principals and their lack of an escape route turning their thoughts and emotions inward. Director of photography Ernest Haller was behind the camera on a number of highly regarded films noir and brought a touch of that sensibility to his work here, the darker nighttime scenes being especially effective.

Dale Robertson was good value as conflicted or ambiguous western heroes – A Day of Fury and The Silver Whip are other examples of this – and the role of John Banner was a suitable one for him. For much of the movie’s running time he’s hardly what you’d call a likeable guy, he’s self-assured and capable but not in a pleasant way. Playing off his swaggering machismo is Linda Darnell, an actress who was always sultry and possessed of her own brand of self-confidence. She goes from cool composure, a relaxed awareness of her feminine power, to borderline hysteria and naked hatred as the tension of the siege and the lack of water gnaws away at her – a strong performance. John Lund turned in a study in enigmatic passivity (but with an undercurrent of justified aggression bubbling just below the surface) for much of the movie before finding himself sidelined to an extent in the latter stages. The honors, however, belong to Ward Bond in my opinion. Bond was a master of bluster, a solid physical presence who could be a figure of fun or a serious threat depending on circumstance. In Dakota Incident he’s just about tolerated by his fellow passengers, although his speeches on racial harmony and his amorous advances towards Darnell are, for the most part, treated with ridicule and disdain. The net result of this treatment is that the viewer feels a good deal of sympathy for the man, the sentiments he expresses are hardly what I’d call objectionable. Given Bond’s real life hawkish tendencies, his casting as such an outspoken liberal works remarkably well and his character comes off as having a lot more integrity than practically anyone else.

I don’t think Dakota Incident has been released on DVD anywhere to date – I have Jerry Entract to thank, again, for my getting to see it. The lack of availability is a shame as it’s definitely worth seeing for the cinematography of Haller and also the casting. I wouldn’t say it’s an overlooked classic or anything of that kind, but there’s a good deal to take from it if you appreciate 50s westerns. In fact, I think that’s a comment which could be applied to a lot of Republic’s output – films which are imperfect in many ways yet different enough, with their own look and sensibility, to deserve a little more attention.

This piece is offered as part of the Republic Pictures Blogathon hosted by Toby at 50 Westerns from the 50s. I’d like to suggest readers visit the site and check out the other contributions to this blogathon dedicated to the films of Republic by following the link above. Alternatively, feel free to click on the badge below, which will take you to the same destination.