My father, usually a quiet man, burst through the door and hustled the family in front of the television set. He said we were on the verge of something terrible and we needed to see and understand. It was October 22, 1962. My father, a career officer at the C.I.A., seemed distressed with things he knew that others did not.

My father, usually a quiet man, burst through the door and hustled the family in front of the television set. He said we were on the verge of something terrible and we needed to see and understand. It was October 22, 1962. My father, a career officer at the C.I.A., seemed distressed with things he knew that others did not.

We then watched in horror as John Kennedy described the Russian missiles west of Havana, capable of reaching our home in Bethesda, and the ordering of a quarantine that would bring us to the brink of global nuclear war.

For the years following my father worked noiselessly within The Company as it plotted a range of assassinations against Castro, including poisoned wet suits and milkshakes, even exploding cigars. Finally, Dad suffered a nervous breakdown, and took an early retirement. For me, in the sparse furniture of my mind, Cuba was a matchstick inches away, ever ready to strike the frictional surface of our shores.

With time, however, the rhetoric hushed, and reports of American travelers finding hospitality and warmth increased. My old friends Michael Kaye and his wife Yolanda, passionate cyclists who have turned their tandem through Europe, North Africa and the Americas, reported that their favorite place to recycle was Cuba. In fact, they asked if I might join their next wheeled adventure, a swing through central Cuba with a daily agenda of community, cultural and educational visits, and, collapsing the many floors of memory, I agreed.

So, with a small group of friends, and my seven-year-old son Jasper, we arrive Havana and wade through a mob of greeters holding signs for tour companies.

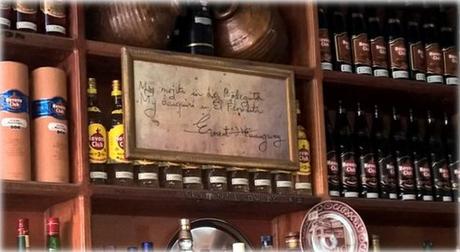

Our outing is not so fancy, and so we grab a taxi, a Hyundai, and, passing the parade of head-turning late 50s American sedans with swooping gull wings for fins, we head downtown, fleeting along the way a huge billboard, “To Hope,” with an image of a missile breaking into a dove. We check into the Sevilla, the first luxury hotel in Havana, filled with photographs of the notorious who strode through, Meyer Lansky, Lucky Luciano, Al Capone, Graham Greene, Joséfine Baker (who had been refused accommodation at the Hotel Nacional because of the color of her skin,) Joe Louis, Ted Williams, and, of course, Hemingway, who supposedly wrote “For Whom the Bell Tolls” between and over mojitos here.

In the sweet liquid light of the Cuban morning we board a Chinese-made King Long tour bus, the same model I used in North Korea a couple years ago. Our guide, José, says King Long means “guaranteed for six months.”

“How long have you had it,” someone takes the bait.

“Twelve months.”

The bus is pulling a customized trailer (with a blown-up picture of a Cuban on a bike carrying a lamb on his back) that holds all the bikes, parts, and some sultry wrenches, so we are self-sufficient for the journey.

A few minutes down the road we pass the Christopher Columbus Necropolis, “the largest concentration of private property in Cuba,” so says José. “People are just dying to get in,” pipes Michaela Guzy, on assignment to produce travel videos of our trip. Many sites are named after the Italian-borne explorer, as he landed here October 28, 1492. He first thought he had entered Asia’s mainland, and was convinced that the name “Cuba,” which was what the aborigines called it, was the Indian name for Japan. Rather, it is a Taino word meaning “where fertile land is abundant.”

We drive five cool hours east to Santa Clara, the gay capital of Cuba, says José, who pays for our snacks with three-dollar bills. It is also a wealthy city, which seems antithetical to the system, but money pours in from Cuban relatives in Miami, and tourism, which long ago passed sugar as the biggest generator of foreign exchange, and is making a significant difference. Most everything is done in cash (no U.S. credit cards accepted…yet), and José shares that if you see someone walking down the street hunched over from a sore back, it likely means he is rich because of the money stashed in his mattress.

We park at the sprawling Hotel La Granjita, which, with its large aqua-blue pool surrounded by coconut palms, and towels twisted like swans on the bungalow beds, seems like it better belongs in Cancun. Here, beneath a canorous refrain of birdsong, we adjust and mount our steeds, Specialized Sirrus Comp Disc Carbon Hybrids with 20 gears.

A banana-shaped and colored Adams Trail-a-Bike is attached to the back of mine, on which Jasper will ride. After a few spins around the parking lot we head off down the road, winding through chaotic traffic, over to Che Guevara’s mausoleum. Che led the rebels in the battle of Santa Clara, a pivotal victory over Batista’s army, which in turn led to the triumph of the Revolution, which in turn led to that moment in which the world was on the nuclear threshold. It all had an aleatory beginning—when the young, privileged medical student, Ernesto Guevara, took a motorcycle trip through South America and was exposed to the widespread poverty, hunger, and disease. He returned transformed, radicalized, compelled to change the world. The rest is history. Today Cuba has weaved the rope of many small advantages: it has a literacy rate of 99.8%; the health system is among the world’s best, and the country has a lower infant mortality rate than the U.S. And they watch all the hot American T.V. shows, such as Deadliest Catch, on pirated thumb drives.

We pass through Cárdenas, famous for being the first place that raised the Cuban flag (designed by Free Masons, José informs), for its bronze statue of Columbus, and for being the home to Elián González, who as a boy in 1999 got caught up in a heated custody battle between the U.S. and Cuba after his mother drowned while trying to make the crossing to Florida.

We pass through Cárdenas, famous for being the first place that raised the Cuban flag (designed by Free Masons, José informs), for its bronze statue of Columbus, and for being the home to Elián González, who as a boy in 1999 got caught up in a heated custody battle between the U.S. and Cuba after his mother drowned while trying to make the crossing to Florida.

Riding some of these roads is like being a funambulist, negotiating that thin line between Soviet Kamaz trucks pumping out huge clouds of black smoke, and pocked pavement that falls off into drainage ditches. Michaela at one point rides too close to the center of the road, and a truck almost clips her, sending her into the pavement. But, except for some minor bruises, she’s in fine shape, and jumps back on her horse, staying now closer the edge.

Cuba is exceptionally pleasant for cyclists because of the role bicycles played during the 1990s. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the dependent Cuban economy did as well. Cubans endured the so-called “special period,” a time of profound economic distress from which the country is still emerging. When gasoline was unavailable during the special period, Cubans turned to bicycles. Hundreds of thousands of clunky but nearly indestructible bikes, the ubiquitous Flying Pigeons, were imported from China, and Cuba soon had its own bike factory. Within a few years, millions of Cubans were traveling on two wheels. Driven by necessity, it was perhaps the fastest, most thoroughgoing transformation in the transportation system of any country in the world.

Now the economy is in higher gear, and more cars and trucks are on the highways. Still, motorists accept the right of cyclists to share the road, and are remarkably courteous, and good at evasive manuevers, even if they wonder why anyone who doesn’t need to would ride a bike for fun.

The tempo of this trip is that we bike in the mornings, some four to five hours, with the bus always leapfrogging from front to back to pick up any convalescents, and then afternoons are free, to swim, study, hike, shop, dance, explore or swill the nepenthe rum.

After our first morning’s ride we reach Sancti Spíritus, home of the Cuban 4-pocket shirts, so often worn by Angel Batista in Dexter. We check into a charming former colonial mansion called Hotel Don Florencio. Though hidden off the main square, once inside it is grand and soigné, with high-ceilings, big doors and large, dark furniture. As is the fashion in Cuba, there are swans on the bed, a slow ceiling fan, and Havana Club in the patio.

The next day as we load our luggage onto the bus, and our driver is sporting a t-shirt that says, “If you like the post office, you’ll love socialized medicine.” We leave town crossing an early 19th century clay-brick bridge arching over the Yayabo River, architecture that looks more akin to the Lake District than a Caribbean isle. On the other side at first we navigate through boodles of cars, motorcycles, trucks, ox carts, horses and pedestrians, but then, after a few busy miles, the traffic thins, the wind cools like a whetted knife on the face, and the ride transports.

We’re rolling through the countryside, passing cattle farms and sugar cane fields. There is a sign proclaiming “artificial insemination” at one farm, “genetic engineering” at another, and so we stop for refreshments betwixt. After a Cristal Beer (do Rappers like this brew?) and some guava paste with cheese, we step out back to a Holy Cow moment. We stare in animal bafflement at a bull with an extra hoof and testicle draped over his back, the results, I can’t help but think, of Castro’s genetic tinkering when he tried to create a Super Cow that could prosper in the tropics.

At last we glide into Trinidad, Cuba’s most feverishly touristic city, a UNESCO Heritage Site, chock-full with art galleries, museums, B&Bs, and international sightseers. “This is the Aspenization of place,” says José, who has never left the island. He leads us along the cobblestone streets, past a chorus of pastel buildings, through the crowds to lunch at Paladar Sol y Son, an atmospheric family eatery where the band plays the required “Guantanamera,” Cuba’s signature song. As many in our versed group, I remember the 1966 easy-listening version by The Sandpipers, which was in turn inspired by a 1963 Pete Seeger rendition. Seeger’s intent was that it be used by the peace movement in the wake of the Cuban missile crisis. Now, it’s a course at every Cuban café and diner.

We pull in our sails for the night at the Hotel Las Cuevas, more cruise ship than resort, with trains of tourist foraging the buffet lines, gaudy entertainers shaking maracas and doing the rumba, bamboo furniture, air conditioning, a disco in a fake cave, and the glittering Caribbean just outside the windows.

After breakfast we spin west to ride along the flat coastline to Cienfuegos. This is the season when millions of small reddish land crabs emerge from the moist forests surrounding the Bay of Pigs to breed in the sea. The migration lasts weeks, and by our passage there are thousands of crushed shells on the road, which we dodge as though a slalom course. Jasper is distressed by the smash-up, but squeals in delight whenever we find an odds-defying live one (he counts ten). He wonders aloud why the authorities haven’t created “crab crossings,” tunnels or bridges that allow safe passage. I wonder why they aren’t eaten, but José explains Cubans won’t touch them as they contain an unpleasant toxin.

We make our way to the entrance to Cienfuegos Bay, and the Hotel Pasacaballo, a mid-70s edifice that looks like the future imagined by Cold War Russian Jetsons. It’s actually a great place to stay, if you want to avoid people, as nobody else seems to be here, even though Cuba is famously short of hotel rooms. The huge pool is drained, and the bar has no gin. They serve suspiciously fresh crab. But, there is a hand-written welcome note in the room, toilet paper in the loo, and comfortable beds, so it serves us well.

In the slanting light of morning we head to the hills. About a dozen miles outside the city the bus drops us at the Cienfuegos Botanical Garden for a walk among the more than 2000 varieties of plants from five continents, including 300 varieties of palms, largest collection in the Americas. José excitedly points to a hibiscus, which puzzles me as they grow like weeds in Cuba, and then asks, “Why are Cubans so great at baseball? Because hibiscus trees make the best bats.”

In the slanting light of morning we head to the hills. About a dozen miles outside the city the bus drops us at the Cienfuegos Botanical Garden for a walk among the more than 2000 varieties of plants from five continents, including 300 varieties of palms, largest collection in the Americas. José excitedly points to a hibiscus, which puzzles me as they grow like weeds in Cuba, and then asks, “Why are Cubans so great at baseball? Because hibiscus trees make the best bats.”

Then we grind upwards, towards the mountain lake Hanabanilla, to the parking lot of El Arabe restaurant, where we unload for launch on a ridge in the Escambray Mountains. José gives us directions for the steep downhill ride: “Riding a bike in a Socialist-Communist country means all the turns will be left.” And he’s right. We crackle down the mountain, brakes pressed against the speed, the smell of cedars and rubber packing nostrils. At times I feel like I’m in a plane coming in for an out-of-control landing at Lukla in Nepal, the most dangerous airport in the world. But somehow, because of some higher force, I stay on course, and Jasper hoots in the back with each high-speed swerve and bump. At the intersections, as instructed, we always veer left, all the way back to the palaces, theaters and clubs at the neoclassical center of Cienfuegos (it was settled in the early 19th century by French immigrants from Bordeaux and Louisiana, and it has a Big Easy feel to it.) We check into the Hotel Jagua, which has the most absurdly stunning ocean views in all directions, and even a distant glimpse of the “Taj Mahal,” the huge concrete dome of an abandoned nuclear power plant, a carbon copy of Chernobyl, which lost funding when the Soviet glass funnel shattered.

As the hot red sunset burns out the remnants of the day, pedicabs take us to the end of Punta Gorda, where we dine at the Villa Lagarto, a poem of a place right on the water. It seems the ideal spot for seafood, but when Thom Beers, the creator of the television hit “Deadliest Catch,” makes an ask for one of his favorites, the waiter shakes his head no. With a smile borrowed from our good friend Havana Club, Thom ripostes: “It’s the Cuban mussel crisis.”

For the final day we take a respite at Caleta Buena, a natural cove with water clear as white rum, busy with bright tropical fish, and on shore, unlimited Cubra Libres. Visually sated, and a bit soused, we board the bus, and after a few hours, we’re back in Havana, walking the Old City, wondering why a cluster of Cuban teens are huddled outside a hotel staring at their cell phones. “They’re stealing the Wi-Fi signal,” José enlightens. After this journey it’s easy to imagine why, in 1959, Cuba broke away from her future in refluent waves, recoiling from a thing unclean, the aristocratic persiflage of rampant capitalism. But it’s also easy to see why they now want it back.

And then, for us, it’s back to the future, back to America, and the frangible certainty we call reality.