Book Review by Jane V: Choosing a novel about the lives of miners in the South Wales coal fields was an obvious choice for me. The last of my forebears to ‘go down the pit’ was my father’s father, born in 1876. He was an only child and his mother did not want him to be a miner, instead preferring him to get an education, just as Len’s mother in the novel does. When my grandfather won a scholarship to an art school his mother was still not pleased, wishing him to stay at home. The compromise was that he became an ‘incline man’ (which I imagine is a man who works at the exit to the mine where the trucks come up from the workings) and taught art at WEA evening classes.

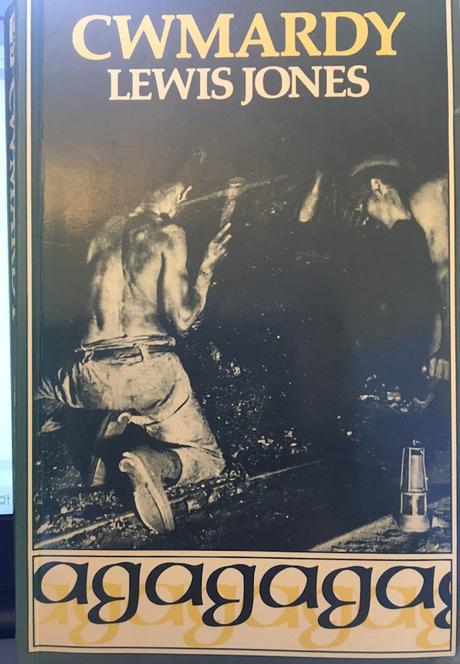

Lewis Jones (b 1897, d 1939) was not a novelist but he was persuaded by the president of the South Wales Miners’ Federation to produce a fictionalised account of the life of a mining family in the Rhondda in the early part of the twentieth century. ‘What I have set out to do,’ he writes in the foreword,’ ‘is to “novelise” a phase of working class history.’ Primarily he was a non-fiction writer producing work on the industry and on politics. Cwmardy tells of the life of young Len from an early age into his politically active adulthood and is what we might categorise today as ‘faction’ or dramatized documentary.

Clearly Len is a part portrait of Lewis himself. The author builds into Len’s story incidents which contribute to Len’s growing awareness of the injustices visited on a mining community by and mine owners and managers and other people in positions of authority. The first of these occurs soon after Len starts primary school. Len and his friend Ron, son of the grocer, have been ‘mitching’ (skiving off school) to go up the mountain where the air is clean and there is a chance to enjoy freedom and exploration. Len, but not Ron, is called out in front of the class by the head teacher, to receive a caning on his hand. When Len withdraws his hand quickly the cane hits the teacher’s leg and, infuriated the teacher sets about lashing the boy across the face. That night Len dreams images of chains. He learns that freedom comes at a price.

Len’s next experience of injustice is when his teenage sister, having been impregnated by a mine official’s son, is cast aside by him and dies in childbirth. Both the lashing and the death are described in great, visual detail. Len’s next initiation into the unfairness of the lot of the working class comes when a terrible mining disaster strikes the pit where his father works the day shift. For added dramatic effect Jones sets this in the midst of a terrific night-time thunderstorm which wracks the valley and all but drowns out the sound of the explosion in the mine. Len’s parents both rush to the pit head leaving the boy alone with his terror. The disaster is described in all its shocking detail and is clearly based on the two disasters at the mine at Senghenydd in the early twentieth century. The actual enquiry after the second disaster decided that the cause was negligence and faulty electric wiring which fired the gasses which gather in a mine. Jones’ version is even more shocking. Managers claim that the fault lies with one of the dead miners who unscrewed his oil lamp to light a cigarette. The inquest goes with this version of the cause despite Len’s father giving evidence that this could not have been the cause as he himself, one of the first down the mine to try to rescue comrades, had checked that the lamp was safe. It was, and had it not been the man would have been blown to pieces before he could screw the lamp up again. When shown the lamp at the inquest it is unscrewed. The coroner’s remark, ‘I cannot for the life of me imagine what interest or motive the management could have in opening the lamp after it came up from the mine,’ shows how management was willing to dismiss evidence to protect themselves. Big Jim, Len’s father knows quite well where the blame lies and it is with the lax safety measures in the pit. ‘If the gobs* had been pinned as they ought to be, there ‘ood have been no blow-up. Us don’t count no longer. Coal be more ‘portant than us now.’ (I found this shocking fact online: after the Senghenydd disaster the manager was fined £24, the mine owners £10. At the time a miner was valued at one shilling, one penny and a farthing, about £6 in 2021 money.)

Before long Len starts work beside his father at the pit. His mother would have preferred him to stay on at school and progress to secondary school and perhaps go on to college, as Ron Evans, son of the grocer does. But Len is determined to follow his dad and ‘be a man.’ Len is clearly an intelligent and sensitive boy but one who sees masculinity in the image of his courageous, proud, brawling, loyal, hard-working father. In fact the crisis of masculinity is one of the themes of the book. Len’s first descent into the mine gives an astonishingly vivid description of the inside of mine workings and the long, arduous trek miners had to make to reach the coal face. For a child of around eleven this is clearly scary and physically very demanding. But Len sticks it out and can’t wait to show his coal besmirched face to his school friends.

As the years go by Len develops a growing understanding the struggle between himself and the coal-face and becomes ‘schooled’ in all the ways a miner must work. ‘In this manner, quietly and stealthily, the pit became the dominating factor in his life. He came to hate the hooter, whose blast he had to obey if he were not to suffer loss of food and pocket money. He came to regard himself as a slave and the pit as is owner’. His old school friend Ron, who is at college, lends Len books on socialism and Len begins to see ‘a key to the problem troubling his mind’. Time goes on and Len falls ill and can’t work for a month. Without his financial contribution his family falls into debt. There is, of course, no sick pay. While Len grows more politically aware he is saddened by the fatalism of his parents and their generation. ‘He felt there existed a callous indifference among them.’ They accept the status quo, things have always been this way and always will be.

The crunch comes when a lack of timber to shore up the roof in the pit shows the power – and indifference of – the fireman whose job is to oversee safety. The miners know that a disaster will follow if more timber is not provided. The fireman prevaricates saying timber will come ‘soon’ but meanwhile the men had better get on with their work. One of the men insults him, he loses his temper and attempts to pull rank, quoting the law and threatening the men with the sack. Discussion follows and Len takes the lead and outwits the fireman. He has noticed some timber lying the other side of the barry*. The men fetch this. But while digging down to insert a prop Bill Bristol is fatally crushed by a huge stone falling from the roof. Big Jim and Bill have previously had a fight, but Jim gently cradles the stricken man’s head until he dies. Len is elected to go and tell the young widow that her man is dead. But he is unable to bring himself to say the difficult words. The community nonetheless understands from the urgency of Len’s run to Bill’s house, that the news is bad. On the day of the funeral the men decide they will not go to work that day. A boldness is beginning to emerge among the men.

Lord Cwmardy amalgamates his mining interests and puts two men in charge of conducting the finances and manning of all his mines in the region. Meanwhile he changes the pay arrangements for the men, paying them nothing for ‘small coal’ which makes up forty percent of their output. Large coal would now be paid one shilling and threepence a ton, a meagre increase of three pence on the old price. This is clearly a cut in pay and the men, after vociferous meetings at which Len emerges as a voice of reason and logic, the workforce decides to strike for a minimum wage. No story of coal mining would be complete without a strike, of which there were many in the mining history of Britain. Lewis Jones launches into this section of the book with all the passion and anger one would expect from a politically active communist and an angry young man. Jones’ account of the progress of the strike from the men’s refusal to enter the mine to their obstruction of the safety men, through violent encounters with the police and finally pitched battle with soldiers brought in to quell riots (the latter account having shades of Peterloo) is evidence of lived experience in its detail and vivid imagery. After fierce fighting and at least one fatality, Era, the miners’ leader, is ready to give up the strike but it is Len who rallies the miners’ flagging spirits with a rousing speech. (Lewis Jones gave many rousing speeches in his short life and died at the age of 42 after giving thirty speeches in one day.)

We can’t expect to fight a battle without suffering hurt, and we can’t expect to win the strike without beating the company and all that it brings against us. We can grieve for our poor butties who have been bettered and shot, but to give in now will be to destroy all the principles for which they have suffered and died. … Let them blow and blast, but never let them force us back to the pit without what we have fought for’.

Stalemate follows and the strike lingers on but finally the directors and Lord Cwmardy are forced to give in to the miners’ demands or lose the pits altogether through disuse and neglect. After a strike of nine months during which public support has provided soup kitchens and clothing to the destitute families, the men return to work and the government introduces a minimum wage act.

Jones takes the narrative through the unionisation of the workers when they agree to join the ‘federashion’. (Jones was ‘checkweightman’ of the Cambrian Lodge of South Wales Miners’ Federation.) The rates of pay improve, and the valley becomes more prosperous. Len and Mary organize the ‘Circle’, a discussion group for young people to engage with political and social ideas. Evening classes begin in the valley (WEA?) Len is exposed to socialism and communism. When WW1 is declared and his father joins up, Len has conflicting thoughts of which way his conscience should lead him. He struggles with socialism v capitalism and the influence these have on attitudes to the war. Most miners are patriotic and rush to join the armed forces but Len also sees that war is a great opportunity for capitalists to enrich themselves without increasing their pay. In the event Len is declared unfit for military service and continues to labor in the pit. Len’s father returns from the war and takes up his old job in the mine. But now the miners have realised their strength and bargaining power in dealing with mine owners and there is a sense that the ‘modern’ era is beginning. Mechanisation begins to be brought in and the port of Cardiff becomes a boom town.

Lewis Jones writing style is impassioned and vivid – almost lurid when describing injuries and conditions down the pit – he is sensitive to the human emotions, as in one of the touching scenes between Len and Mary, daughter of Ezra the miners’ leader.

‘There is so much to be done and I am so weak when I am by myself. I feel if you were with me all the time both of us could do so much more just because we were doing it together. Sometimes when I am lonely, I think of you and my body goes warm as I imagine that you are close enough for me to whisper in your ear all the thoughts that crowd into my mind.’

It is only when describing scenery that Jones waxes embarrassingly ‘purple’. Here he is carried away describing the thunderstorm which accompanies the explosion in the mine –

‘Thunder wantonly joined in the game. Its unholy laughter rolled and crackled, tearing the air in a devil’s chorus of reverberating echoes . . . ‘

I very much enjoyed this novel which I feel educated me in a theatrical and engrossing way. It occurs to me that Cwmardy could be material for a great film or tv series. All the drama and human characters are already there and the story line is history.

*’gob’ from Welsh ‘gof’ – cave. A void from which all the coal in a seam has been extracted and where the roof is allowed to collapse in a controlled manner. If not allowed to collapse it must be propped. The void acts as a ‘pocket’ in which dangerous gasses collect.

* ‘barry’ I think this must be a section of the pit where the men are currently working.