Crimson Gold opens on a static shot in darkness as a scuffle is heard over the soundtrack. The black of the title card gives way to an undulating, impenetrable molasses eventually revealed to be a man pressed up against the camera. His attacker pulls him back, revealing a giant, shadowed man holding an old jeweler as he demands the key to the safe. The thief drags the man out of frame, but the camera does not follow, now looking outside the door as an accomplice stares uncertainly and a potential customer obliviously pulls up and walks in, even making conversation before she spots the gun and screams. The distraction allows the jeweler to set off the alarm, trapping the robber inside. In a huff, the man shoots the jeweler and looks outside as a crowd gathers to gawk at the caged animal. At last, the camera begins to zoom in on the man, who turns around to face the camera, backlit by the bright sky outside. Realizing his fate, the man at last turns the gun on himself, the camera at last cutting as the shot rings out.

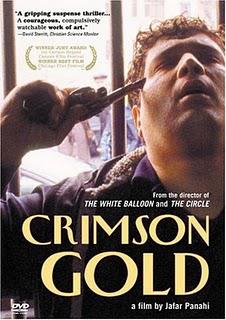

Crimson Gold opens on a static shot in darkness as a scuffle is heard over the soundtrack. The black of the title card gives way to an undulating, impenetrable molasses eventually revealed to be a man pressed up against the camera. His attacker pulls him back, revealing a giant, shadowed man holding an old jeweler as he demands the key to the safe. The thief drags the man out of frame, but the camera does not follow, now looking outside the door as an accomplice stares uncertainly and a potential customer obliviously pulls up and walks in, even making conversation before she spots the gun and screams. The distraction allows the jeweler to set off the alarm, trapping the robber inside. In a huff, the man shoots the jeweler and looks outside as a crowd gathers to gawk at the caged animal. At last, the camera begins to zoom in on the man, who turns around to face the camera, backlit by the bright sky outside. Realizing his fate, the man at last turns the gun on himself, the camera at last cutting as the shot rings out.Only the greatest of artists could dare to place an ending such as this at the beginning, but Crimson Gold bears the input of two of the greatest today: Jafar Panahi and Abbas Kiarostami. Panahi, who got some of his first post-collegiate work as an assistant director under Kiarostami on the latter's Through the Olive Trees, has collaborated with the Iranian master through his career but has his own artistic identity. Where Kiarostami reaches for the bigger target, bypassing national boundaries to make observations on all humanity, Panahi cannot overlook the tangible ills plaguing the society in which he lives. Together, the two bring out the best in each other: Kiarostami's writing channels his understated but razor-sharp wit toward more pointed political satire, while Panahi's direction absorbs some of the poetry inherent even in Kiarostami's scripts.

Like his mentor, Panahi loves shots of vehicles traveling, but where Kiarostami changes up his long-extreme long shots for shot/reverse shot close-ups inside a car, Panahi maintains the same distance throughout (typically a medium long to mild long shot) and moves outside the vehicles. Here, Hussein, the man who robbed the store and shot himself at the start before the film flashed back two days, drives a motorcycle, typically carrying his friend and, later, accomplice Ali. Their conversations are terse, and where Kiarostami normally uses trips to subtly bring out the philosophies and traits of his characters, here he deliberately walls Hussein off, preventing any deeper reading of that blank face or those dead eyes.

The nonprofessional actor playing Hussein, Hossain Emadeddin, is purportedly a paranoid schizophrenic, and while clues are dropped regarding a past in the Iranian military and a need to take pain medication, neither Panahi nor Kiarostami does anything to suggest that the character has the same condition. But the hint of boiling emotion and internal war raging behind the expressionless face complicate the otherwise banal Hussein, which in turn gives his flat line readings an untraceable menace. Of course, the fact that we saw the end of his life first, a darkly comic but ultimately despairing murder-suicide also contributes to the attempt to figure out what made the gentle man snap.

As with so many Kiarostami-penned films, however, Crimson Gold does not settle for easy linearity, even the tangled linearity of a psychological breakdown. Throughout the film, I thought of Kiarostami's The Wind Will Carry Us, in which a director travels to a remote village to film an old woman's death, only for new ideas to arise when she stubbornly continues to live. The piercing wit of that film gives way to a more pointed political examination of modern Iran, albeit one filtered through a humanism that blunts polemics.

Hussein, working as a pizza delivery man, rides his bike around the disjointed metropolis of Tehran, routinely wanders into the wealthy districts to make deliveries, and the juxtaposition of his simple clothing and stark living conditions and the almost Western level of comfort enjoyed by the rich is eye-opening, unmissable yet understated. On the first delivery we see, Hussein buzzes in at an apartment complex, and the man who answers tells Hussein that the elevator is broken and makes him abandon his bike and climb four flights of stairs. Hussein heads up there, and when the customer opens the door we see red-painted walls and candles.

The pizzas cost 18,500 tomans, roughly $18. This well-off man gives him 19,000 and tells him to keep the change. Hussein does not budge. Just as I thought he would strike the man for this infuriating offense, Hussein introduces himself and reveals that he and the man served in the military together. Struck by the realization, the customer gives him a larger tip out of sympathy but clearly wants to avoid anything but the barest discussion with this lumbering man, bloated by cortisone and spare pizza. Even among war buddies, some just get forgotten.

That brief moment conjures a plethora of feelings, from social outrage to frigid comedy to heartbreak, all of which inform the film's most memorable (and long) sequences. The first is a masterpiece of anti-comedy, as Hussein travels to an apartment complex to deliver a stack of pizzas to a party. Just as he reaches the intercom, a policeman walks up and pulls him aside. As it turns out, the police and military are staking out the party and waiting for people to come down. Why they are doing so is never said; the camera stays with Hussein, who is made to go stand aside, unable even to leave because he is now a "witness." For what feels like forever, he stands next to a teenage soldier as people arrive at the apartment and are detained as the police wait for the partygoers to leave so they can be arrested.

Proving the combative, non-submissive nature of the Iranians, everyone protests being pushed around by the police, not a one of them simply following orders. But Panahi does not come down too hard on the cops: Hussein, aware that he will not get to make his delivery, offers the pizza to the police chief, who accepts a slice, then to the rest of the cops. Hussein spends most of his time standing next to a teenage soldier holding a rifle about as tall as he is, nervous with anticipation and fear. He tells Hussein he'll shoot anyone who makes trouble, but he has no clue why he's waiting for rich people to stop carousing and disperse. Panahi pulls back the camera just enough to capture an eerie, pale green glow mingling with soft moonlight. He moves around the alley slowly, taking in the absurdity of the situation and how everyone there is trapped by forces they cannot explain.

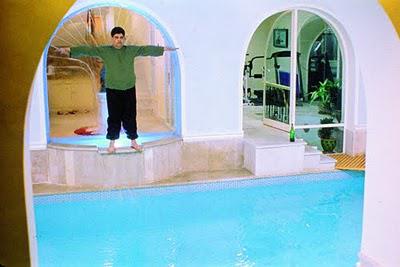

Near the end of the film, Hussein makes another delivery, this time to an absurdly lavish apartment. The man who answers the door is huffy, the two women he invited over having left abruptly. They wanted the pizzas, he rants, so why should he pay for them? Hussein barely listens; the camera cuts suddenly to a POV shot of his head whirling around the sights behind the customer's head, the fast tilts and pans relaying the stupefying impact of the marble staircase, Greek statues and other adornments on a man who, only minutes earlier, we'd seen return to an apartment with naught but a minuscule poster dotting a cracked concrete wall.

Guilty for subjecting Hussein to his invective (yet also wanting to keep him around to vent more), the man invites him in to share the pizza and talk. The mult-tiered apartment is an astonishing setpiece, displaying the dominant Western influence among the rich. Hussein stumbles around in a stupor even before he later gets drunk and jumps into the indoor pool, but Panahi does not attack the rich for the extreme disparity between the haves and have-nots: the man, who lived in the West but returned to his parents' pad out of homesickness, is nouveau riche but not condescending toward Hussein. As can be seen with the women, who darted out of the complex in Western clothes, even the rich are restricted by social repression. The man calls the women sluts in his anger, but the clear implication is that they left because he was trying to coax them into a threesome. As is always the case, a sexually repressed society obsesses over sex and its implications far more than a liberal one.

This is but one commentary Panahi makes on the plight of women here. The two films that surround Crimson Gold, The Circle and Offside, directly concern women. Here, Panahi's holistic approach to the clashing forces pulling at Iranians incorporates his gender observations into other facets of shifting yet frustratingly static Iranian lifestyles. During the protracted police stakeout, a married couple returns to the apartment and tries to go back to their place. The police grill them as to what they were doing, and they protest that they were just going out. "What kind of a man goes out with his wife?" asks one cop without a hint of irony, seriously unable to imagine such a scenario.

Even the main characters exhibit sexist views. Ali is a pickpocket who steals women's purses, yet no one seems to care. He even empties one out on a table in a restaurant without anyone raising an eyebrow. Hussein is set to marry Ali's sister, and Ali admits he worried no one would have her. As he rides on Hussein's bike, he tells his friend as they pass ladies, "I look more at the purses than the women" even as he gently tests Hussein's restraint by tempting him to look at other women.

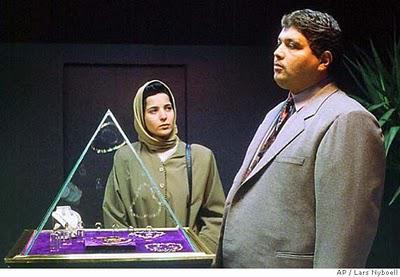

Hussein too seems to bear some of the socially ingrained sexism: he brings his fiancée with him to the jewelry store he will later rob, and when she lifts up her shawl for only a moment to try on a necklace, Hussein's icy demeanor cools even more. He heads to the jewelry shop several times looking to buy her something, yet when she appears with him he scarcely says three words to her. He just wants the condescending old man who runs the place to acknowledge him and uses his fiancée as an excuse to return there.

Panahi's cultural criticism is unique: it is plain and unhidden, be it the difference between the respectful oppression the rich suffer compared to the battered-down doors and shouts the poor endure, the subjugation of women or the influence of the West that appears to have seeped in only in materialistic ways. Yet he also crafts subtle, even poetic ruminations from the obviousness of his targets, and if the setup is always predictable, the payoff never is. Crimson Gold takes such turns and moves with such dreamlike imprecision that I forgot Hussein would kill someone else and then himself by the film's end. First, I expected an anti-heist movie in the vein of Sidney Lumet's Before the Devil Knows You're Dead, then something akin to Taxi Driver and it Dostoevsky-inspired breakdown. But I was foiled at every turn: the stakeout, with its soft neon glow, long-shot comedy and exquisite framing, looked like something out of a Tati film, while the other major sequence brings forth a despair in Hussein amidst the modernity of the rich man's accoutrements that, though the feeling was not as strong as the Tati connection earlier, made me think of Ozu.

When Ali sifts through the woman's purse near the start of the film, an old con artists walks over and marvels at the openness of their theft. He instructs them not to steal simply for the pocket change of a poor woman's purse or for the thrill of the chase but to understand one's motives and one's existential need to steal. He leaves them his card, leaving open the possibility of him becoming a mentor to Hussein and Ali, but they never contact him. Hussein simply resents being dismissed so casually by the man and continues on without ever figuring himself out. We can guess at why Hussein eventually murders the jeweler -- in keeping with the slight connections to Taxi Driver, I kept thinking about the protagonist's encounters with the uncaring officer in Notes from Underground and how badly Hussein simply wanted to be acknowledged by his "foe" -- but answers remain insidiously out of reach.

“If you want to arrest a thief, you’ll have to arrest the world," recites the old con artist to the men, and as Hussein emptily wanders around Tehran without expression, one cannot help but feel that someone or something has stolen a piece of him as well. Without that missing piece, Hussein is incomplete and less than human. So invisible is he that, in the end, Hussein must hold a gun to a man's head just to see a necklace. The dark comedy of the beginning now morphs into engulfing despair: I laughed fatalistically at the doomed fool, and now I wanted more than anything to find some way to get him out of that shop before he did what he was fated to do. Kiarostami and Panahi do not yank the carpet out from underneath you, they gently slide you off a plank.