Index funds have become the go-to for many investors and for good reasons. They’re easy to buy and sell, they’re really inexpensive with very low fees, and can really be used by anyone with only a tiny amount of knowledge about investing. The biggest reason that people use index funds is that many studies have shown that index funds beat most managed funds over long periods of time. That’s right, buying and holding a simple set of stocks selected to reflect the returns of a portion of the market, does better than most funds where there is a team of professional managers buying and selling stocks!

(Note, while you’re reading this for free, it is not “free” to put all of this great information together for you. Hundreds of hours, an average of two to three hours per article, have been spent researching and writing these articles for you to use and hopefully better your life. One way that you could pay back and keep me writing more great articles like this one, while getting a lot of great information, is by purchasing one of the books, The SmallIvy Book of Investing or FIREd by Fifty: How to Create the Cash Flow You Need to Retire Early. Reading these books will make you very knowledgeable in money management and investing and give you the secret to reaching financial independence. Buying a book and writing an honest review in Amazon would be even more helpful.

But that last statement is somewhat deceptive and may be causing people to default to index funds when they would really be better off selecting their own portfolio of stocks. While it is true that an index fund will beat out most managed funds in the same area, this does not mean that they will beat out a properly developed portfolio of stocks if invested and managed properly. In this article we’ll go into what index funds are, why they tend to outperform managed mutual funds, and how you can do even better than the indexes if you’re willing to put a little effort in and build your own portfolio.

What is a Mutual Fund and How Do Mutual Fund Fees Work?

A mutual fund in general is a financial device where individuals pool their money together to buy a basket of stocks (or bonds, rental houses, etc…) where each individual owns a portion of the basket (known as a portfolio) based upon how much he or she invested. For example, if 11 people got together and ten invested $10,000 and the last person invested $100,000, they could then buy $200,000 worth of stock. The first ten would each own 5% of the account and the last would own 50%. If the stocks went up 100% and the portfolio was then worth $400,000, the first ten investors would have a stake worth $20,000 and the last would have one worth $200,000. If the portfolio of stocks generated $5,000 in income each year (paying out a portion of their profits in what are called, dividends), the first ten people would get $250 each and the last would get $2500.

A money manager or a group of managers is hired to select the stocks that go into the mutual fund. There are also administration individuals who take care of keeping track of ownership stakes, complying with regulations, paying the managers and administrative people, sending out statements, and other functions. These salaries and other expenses running the fund generates are paid out of the portfolio in what are called fees. The fees are typically charged to each investor based upon the size of their ownership stake, so the eleventh investor in our example would pay ten times as much each year as the other ten investors. These fees directly reduce the amount the investors receive, so if the mutual fund earns 10% in a given year, based on increases in the stocks in the fund and the value of the dividends received during the year, but the fees add up to 2% of the value of the fund, then the investors would only see their investment increase by 8%. The other 2% would be swallowed up in salaries, benefits, and office expenses by the fund management team.

Don’t have money to invest? The first step is getting hold of your personal finances so that you have money left over. Pay off debt so that you can stop paying interest and use that money to put toward investments. Dave Ramsey is the guru of getting out of debt and reaching financial peace. Once you’re out of debt, check out FIREd by Fifty to learn how to then grow your wealth by controlling your cash flow and investing.

Obviously, the higher the fees are, the more investment returns are reduced. Some funds brag about how their managers travel the country (or the world), meeting with companies to gather information to help your investments. That may sound great, but all of that travel costs money, and mangers and their staffs are more likely to be eating at fancy steak houses than Denny’s when they’re on travel. After all, it’s not their money. This reduces fund returns to the point where any gain created by having a skilled team picking stocks is wiped out by the expenses, and then some. This totally removes the advantage of having a good management team.

FIREd by Fifty: How to Create the Cash Flow You Need to Retire Early

Enter Index Funds

Way back in the late 19th century, Charles Dow created a set of three indexes. These were a theoretical portfolio of stocks designed track a certain portion of the market. Basically, the idea was that if the index went up, companies in general in that sector of the market were doing well. He did this to help quantify how well different segments of the market were doing. He created three indexes, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, The Dow Jones Rails Index, and the Dow Jones Utility Index. These three indices remain today, although the Rails was renamed with the Transportation Index when things like airlines and trucking companies were added.

The Industrial Index, or DJIA, was designed to track the major industrial companies, the Rails Index to track the railroads, and the Utilities Index to track the utilities. Later, Dow created a market theory known as “Dow Theory” which used the behavior of the Industrials and the Rails to determine whether the market in general was going up or going down. It is from this theory that the idea of bull and bear markets was formed. (If you really want to understand what a bear market is, which the news media gets wrong all of the time, check out this article.) (If you’d like to learn more about using Dow Theory to help you time when you buy and sell, check out the bible of value investing, The Intelligent Investor, written by Warren Buffet’s mentor, Benjamin Graham.)

Over time, other indices were created, such as the S&P500 Index, which tracks 500 large companies, and the NASDAQ Index, which tracks a set of large companies mainly in the technology area. People started to use these indices to determine how well they were doing by comparing their results against the index results, essentially seeing how their portfolio did relative to what the given segment of the market did. People also started to compare the returns of their managed mutual funds to the returns of the index. They found often that, after fees were included, they would have been better off investing in the index than they were investing in their funds with the management team. The issue was that they didn’t have the ability to invest in an index, it was just a theoretical grouping of stocks.

Then, the S&P company got an idea. They created a new investment device that they called a “Standard&Poor Depository Receipt,” to which they gave the name SPDR, pronounced “SPiDeR,” to make it more sexy for marketing. Someone who bought a set of SPDRs would be buying a portion of a portfolio designed to follow the S&P500 index as closely as possible. SPDRs were traded among individuals like shares of stock, so the managers didn’t need to buy and sell shares of the underlying index stocks as investors entered and left. They just bought the shares of the companies comprising the indexes initially, then let investors trade ownership stakes in the basket of stocks among themselves. This made them very easy to manage and, more importantly, cost efficient, meaning fees were way lower than those of managed mutual funds. Thus was born the first index fund.

Vanguard championed the use of index funds under the direction of founder John Bogle. A group of investors who used index funds exclusively was formed, creating an online forum that is a great place to go to ask for investing advice and questions about investing in general. Individuals from this group, which call themselves the Bogleheads after John Bogle, also wrote a book called The Bogleheads’ Guide to Investing that is a great resource for those wanting to learn index investing. (If you want to learn all about the different investing options and the risks involved, the first few chapters of The SmallIvy Book of Investing fully covers this material.)

Index funds are a great way to invest because the fees are really low and it allows the investor to easily spread his or her money out over several different stocks. For example, you can buy an S&P500 index fund, putting your money into about 500 large US stocks, and only pay about 0.05% per year, or 50 cents per $1000 invested. This compares with managed fund fees which can be 2%, or $20 per $1000 invested. If the manager is able to produce superior results, such that you’re making up for this difference in fees each year, it can be worth the added expense to buy managed funds. Because this is not the case most of the time, however, index funds are the better way to go.

The Issue with Index Funds

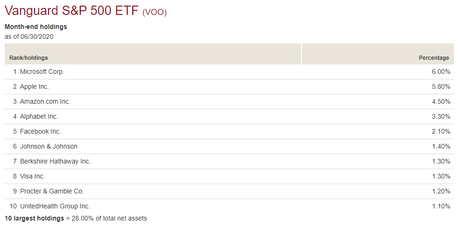

A big issue with index funds is that they tend to overweight stocks in the index that go up in price and grow large. For example, if you were to buy into an S&P500 fund today, you might think that you would have your money spread out evenly over 500 stocks. In actuality, you’d have almost 30% of your money invested in just 10 stocks, and those stocks are highly concentrated in the technology sector. From the Vanguard website, the holdings in their S&P500 ETF were, as of the end of June:

Notice that you’d be putting about 12% of your investment in the two largest holdings, Apple and Microsoft. Rather than spreading your money out relatively equally into 500 stocks, you’re concentrating it in a few big tech stocks while buying very little of other companies. This is great if technology companies are doing well, but if the technology sector suffers a big decline, which it will periodically, your index fund will go down far more than a portfolio that contained each of the 500 stocks in relatively equal amounts.

The other issue is that everyone in the country practically already owns shares of Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, etc…. This means that people are already invested in these companies about as much as they are planning to do, so there is very little demand to buy more shares and drive the price higher. These big, household-name companies will increase in price as their earnings increase, but not as much as they would if people were buying more shares of them and adding to their portfolios. So, you’re concentrating your investing in stocks that have already gone way up and are unlikely to outpace the market over the next several years.

Why You Should Make Your Own Index

A solution to this issue, if you have about $10,000 or more to invest, is to build your own index fund using individual stocks. You then have the power to ensure the positions are relatively balanced and avoid concentrating in what everyone else is buying. You would do this by selecting a set of stocks which cover the area of the markets in which you wish to invest and then investing relatively equal amounts in each company. This would mean that your money would be spread out over different stocks and industries rather than being concentrated in a few stocks and in a single sector.

One argument against this strategy, which is detailed in The SmallIvy Book of Investing and called serious investing, would be that picking stocks has been shown to not be as effective as buying index funds. As stated earlier, professional money managers with all of their education and resources are not able to outperform index funds, so why would a small investor be able to do so? It is certainly true that you are very unlikely to outperform the index funds if you are trying to trade stocks, where you are buying and selling frequently in an effort to buy in when things are good and sell before stocks decline.

(Want to become an expert in single stock investing, plus learn what you need to be doing at each stage of life to grow wealthy? Get a copy of The SmallIvy Book of Investing.)

But what you would be doing in creating your own mutual fund would not be stock trading – you would not be buying and selling shares regularly in an effort to try to time the markets. Instead, you would be accepting the fact that you would not be able to predict when the markets would rise or fall, or which segment of the markets will do better or worse over a given period of time, and instead buying positions to cover the whole market equally. In this way, you’d always have some money invested in whatever is doing well at the time. You are just spreading your money out evenly by purchasing shares directly rather than buying an index fund which is not balanced.

For example, you might buy equal positions in 10 large US stocks. Rather than trying to time the markets, you then hold onto those positions, only buying or selling periodically to rebalance out your positions when one or more companies begins to dominate the portfolio. It is the act of trying to time the market that usually causes people buying individual stocks to not get market returns, not the act of buying individual stocks itself. You’re avoiding this buy buying and selling only to keep the portfolio in balance.

How to Build your Index Fund

OK, so now we can get down to the mechanics of implementing this strategy and building your fund. Let’s say that you have $10,000 and you want to build up an index of large US companies. With that amount of money, a strategy would be to select five companies to build your initial portfolio, each one in a different industry. This is done to diversify your investments out so that you’ll always be invested in whatever segment of the market is doing well at any given time. For example, lets say we choose to invest in technology, banking, travel, retail, and healthcare. We would dedicate about 20% of our money, or $2000, to each segment.

We would then choose one stock in each of these market segments for our investment. Here is where learning how to evaluate companies and pick stocks comes into play since you can then try to pick those stocks in each industry that will outperform the others. This is a skill that you develop over time, however, and requires that you both learn about stock analysis and get experience picking stocks. Given that the worst you can do is lose $2000 in each market segment, however, just choosing names you know and companies that have been profitable in the past (you can check sites like Yahoo Finance to see which companies are making money) can suffice to start.

So, let’s say we choose Microsoft for technology, Bank of America for Banking, Marriott for travel, Walmart for retail, and Johnson and Johnson for healthcare. Based on current prices for these stocks, our portfolio would look like this:

CompanyPriceSharesValue

Microsoft$20310$2,030

Walmart$13215$1,980

Marriott$91.5022$2,013

Johnson and Johnson$150.0013$1,950

Bank of America$23.2586$2,000

Total$9,972.50

Example Portfolio of Large US StocksNote that the need to buy in even share increments made the portfolio a little uneven, but we got as close as we could tho equal investments. We would put in limit orders for each of these stocks to make sure we stayed under the price we wanted. We would also need to factor in brokerage commissions when purchasing the shares. For example, if it cost $25 per trade for commissions in our brokerage account, we would reduce the number of shares purchased to cover these fees (or come up with more money to invest).

Maintaining our Index

Once we make the initial purchase, we would only make changes as needed to keep the balance. This is because we don’t want to try to time the markets since this is a losing strategy and adds to our costs. The more we trade, the more we pay in commissions and taxes. Instead, we would blindly do what was needed to maintain the balance and let the markets take care of the rest. This rebalancing would only be needed to be done about once per year – it is better to leave things alone and let winners run for a while than to try to keep the percentages exact constantly since stocks do tend to continue going up for a period of time once they start and build up what is called momentum.

If this portfolio is held within a tax-advantaged account like an IRA, we could just buy and sell as needed without concern for taxes. If it were in a standard, taxable brokerage account, however, we would want to be tax-smart about how we rebalance. Specifically, we would want to avoid selling shares at a gain unless we were also selling other shares at a loss to offset the gains. Note that we could trade one of the stocks we own and in which we have a loss for another in the same industry as a way to take a loss. For example, we could trade out shares of Walmart for shares of Target. Offsetting gains with losses like this would reduce our taxes or even keep it tax-free. This is a big advantage of buying individual stocks over buying index funds – we can often rebalance without paying capital gains taxes by offsetting gains against losses. If you hold index funds for a long time, it is likely that you’ll only have gains and no losses, so you’ll be paying taxes each time you sell shares. (Note, this can get a bit complicated, with things like short-term and long-term gains, so check with a CPA or do your own research to understand the laws.)

An easy way to rebalance if we’re adding money to the portfolio is to direct new purchases to the stocks that have the least amount of value. For example, let’s say that after a few months we have about $1000 more to invest and the portfolio looked like this:

CompanyPriceSharesValue

Microsoft$18310$1,830

Walmart$12515$1,875

Marriott$80.0022$1,760

Johnson and Johnson$259.0013$3,367

Bank of America$35.0086$3,010

Total$11,842.00

Portfolio after three monthsWe’ve made a nice, 12% gain with the advancing positions exceeding the losing ones. Positions in Bank of America and Johnson and Johnson now dominate the portfolio, however, putting us out of balance. With the new money, we might choose to buy 5 shares of Marriott for $400, 3 shares of Walmart for $275, and 2 shares of Microsoft for $366. After these purchases, our portfolio would now look like this:

CompanyPriceSharesValue

Microsoft$18312$2,196

Walmart$12518$2,250

Marriott$80.0027$2,160

Johnson and Johnson$259.0013$3,367

Bank of America$35.0086$3,010

Total$12,983.00

Portfolio after balancingNote that we still wouldn’t be fully balanced, but things would be closer. We could also put the whole $1000 into the stock with the lowest balance, buying 12 shares of Marriott in this case, and then invest the next $1000 in whatever is underrepresented later at that time. If we’re paying commissions by the trade this would be the best way to invest new money since it would minimize the number of trades made. We might also wait to invest until we had more cash built up if brokerage commissions are a big issue. Alternatively, we could also look into using dividend reinvestment plans, where we send money directly to the companies to buy more shares, as an alternative way to buy more shares cheaply.

(If you enjoy The Small Investor and want to support the cause, or you just want to learn how to become financially independent, please consider picking up a copy of my new book, FIREd by Fifty: How to Create the Cash Flow You Need to Retire Early This is the instruction manual on how to become financially independent.)

Have a burning investing question you’d like answered? Please send to [email protected] or leave in a comment.

Follow on Twitter to get news about new articles. @SmallIvy_SI

Disclaimer: This blog is not meant to give financial planning or tax advice. It gives general information on investment strategy, picking stocks, and generally managing money to build wealth. It is not a solicitation to buy or sell stocks or any security. Financial planning advice should be sought from a certified financial planner, which the author is not. Tax advice should be sought from a CPA. All investments involve risk and the reader as urged to consider risks carefully and seek the advice of experts if needed before investing.