For the last decade, David Cronenberg has retreated from his body horror nightmares of modernity and moved into the traumas that inherently exist in life, well outside contemporary anxieties. The postwar kitchen sink drama cum shattered mental breakdown of Spider. The instinctual savagery of man displayed even in the title of A History of Violence. The histories made visible on bodies via gang tattoos in Eastern Promises. The formation, and potential inadequacies, of theories to explore the psychology of all of this in A Dangerous Method. The old monsters still remain, if they are not as visible. Where the mind tends to ooze out of suppurating wounds in prior Cronenberg films, the dynamic reverses in Spider to make the body horror internal as the body collapses into the mind. In A Dangerous Method, it is Keira Knightley herself, her jutting jaw and angular frame thrown into disarray as her illness complicates the work and professional relationship of its two psychiatrists.

For the last decade, David Cronenberg has retreated from his body horror nightmares of modernity and moved into the traumas that inherently exist in life, well outside contemporary anxieties. The postwar kitchen sink drama cum shattered mental breakdown of Spider. The instinctual savagery of man displayed even in the title of A History of Violence. The histories made visible on bodies via gang tattoos in Eastern Promises. The formation, and potential inadequacies, of theories to explore the psychology of all of this in A Dangerous Method. The old monsters still remain, if they are not as visible. Where the mind tends to ooze out of suppurating wounds in prior Cronenberg films, the dynamic reverses in Spider to make the body horror internal as the body collapses into the mind. In A Dangerous Method, it is Keira Knightley herself, her jutting jaw and angular frame thrown into disarray as her illness complicates the work and professional relationship of its two psychiatrists.Cosmopolis bridges the earlier, topical body horror with the abstract, unseen terrors of Cronenberg’s late period. Indeed, in this film, the monster may be the camera itself, an Arri Aflexa that renders a picture of undeniable ugliness. Black levels pool like ink, unreal colors bleed into each other, and attempts at old-school in-camera effects make some of Hitchcock’s laughable rear-projections look like location shoots in comparison. That this is all clearly deliberate does not, on the face of it, serve as a full defense of the garish unpleasantness of the frame, and those alienated from this alienating movie cannot be blamed much for pushing outside of it. Speaking for myself, though, Cosmopolis is just about the most enthralling film of the year, capable of sucking in a viewer into the same black hole that consumes the image and the strange (and even more strangely delivered) dialog. Not explicitly an apocalypse movie nor a Death of Cinema picture, Cronenberg’s latest feels like both, as the sudden meaningless of money threatens to take the world (and film) with it.

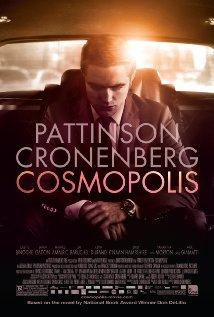

The film focuses on Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson), a young business genius and head of his own mutli-billion-dollar corporation. With the president in town and sparking traffic and protests, Packer informs his head of security (Kevin Durand) that “we” would like a haircut, specifically one from a barber all the way across a gridlocked Manhattan. That, more or less is it, though the film’s draining power comes from the arduous slog of the limo’s creep through town and the strange, distanced conversations Packer has in and out of his vehicle.

Pattinson, of course, is known for playing a vampire in the Twilight pictures, and here he carries himself a bit like Count Dracula, at once dignified and animalistic. He has sex with his art dealer (Juliette Binoche, all feline slink) with his hands behind his back before casually telling her he wishes to buy the Rothko Chapel and put it in his flat. He views violence with dispassion, even a smirking sense of entertainment, as he does when he sees the head of the International Monetary Fund get gruesomely killed or when an Occupy-like protester immolates himself outside Packer’s limo. The billionaire looks upon the latter with such complete remove that he ends up arguing about the unoriginality of the act with his “head of theory” (Samantha Morton), debating the sight on its grounds as a statement and dismissing it for lacking sufficient relevance and that “new” quality.

Cronenberg clearly repositions DeLillo’s novel for the 99% era, and the film aestheticizes Packer’s separation from the world just outside his bulletproofed windows and cork-lined, noise-cancelling doors. Pattinson speaks in arch dialogue, his royal “we” one of the least insufferable, incomprehensible things to come out of his mouth. He manages to be both blunt and abstract, and his line readings hit disharmonies within the natural rhythms of speech to make his speech yet more jarring. Interactions with other members of his small world provide yet more alienating talk, be it Morton’s theoretical notion that “Money has lost its narrative value” or Sarah Gadon’s wonderfully chilly performance as Packer’s new, sex-averse bride. Her reading of the line, “I smell sex all over you,” is perfectly perched between reproach and apathy, as if some part of her feels angry over her (correct) assumption of his infidelity but the rest of her is beyond caring.

Complementing the detached dialog is some of Cronenberg’s most subversive direction. Everything about the look of Cosmopolis serves to distance Packer from the audience as much as his limo acts as a barrier between himself and the mounting unrest outside. The aforementioned inkiness of Peter Suschitzky’s digital cinematography comes into play with the black leather of the limo interior, in which everything is made inhumanly slick. This feeling is compounded by the pale glow of electronics casting an eerie, unnatural light on faces. These are garish and subtly unnerving tricks that Cronenberg takes even further by the way he gradually tilts the direction of its axis, decentering the actors and using different focal lengths to warp the spatial properties of the frame. Heads hang away from their bodies with more sense of stereoscopic depth than 3D has yet produced, and a close-up of Binoche’s arm seductively reaching for Pattinson is stretched beyond reason until the shot resembles King Kong’s mighty paw groping for Fay Wray.

Cronenberg’s typical direction resembles a doctor noting his diagnosis into a tape recorder, a clinical observation of physical and psychological traumas disturbing in its remove. Here, his camera becomes a part of the story, its image altered by a collapsing system and, more personally, Packer’s mounting stress as his bet against the value of the Chinese yuan becomes more and more foolish. The positioning of Packer as an anthropomorphization of the economic crisis is obvious, but it is the way that the camera, rather than coldly document, subjectively becomes that disaster as well that the film achieves its true power. Funny, then, that this newfound intimacy should prove more divisive and repellent for many than the rest of Cronenberg’s filmography.

The central conflict, then, lies less within its comic depiction of the 1% watching the poor literally burn as the world falls apart than the struggle of humanity against these new, digitizing forces. Technology has its own text, with its various programming languages, and its own forms of visual communication, as seen through the off-putting cinematography. Yet if the film practically dares the audience to hate it, it also does not truly embrace its revulsion, and one is left with the sense that the issue is not that new technologies are edging out humanity but that humanity is dragging its feet on its own evolution.

Technology (and the world it powers) now evolve so quickly that even Packer, in Pattinson’s 26-year-old body, admits he feels old and obsolete when confronted with an even younger whiz employee. Paul Giamatti appears at the film’s climax as a disgruntled ex-employee, the rat imagery used throughout the film finally made manifest in that most rat-like of character actors. Clammy and nervous, Giamatti’s Levin wants to kill Packer, less for revenge at being fired than as an outlet for his bewilderment at a world that now makes money by the nanosecond and thus requires constant calculations and communications faster than humans can process. When Packer confronts Levin and invites his “credible threat” to sit and discuss philosophy with him, both men almost betray a sense of relief that, despite the tension of their interaction, they can take a second just to get their bearings.

Giamatti’s shivering, despairing stalker helps visualize the fear and anguish Packer will not permit himself to show, save only for the most unexpected of triggers. The death of a favorite musician elicits his only tears, while the childhood barber he finally reaches near the end provides a level of comfort for him that no longer exists as his world changes. Where the digital focus of the film ties Cosmopolis to Cronenberg’s trendy technological horrors (think Videodrome and ExistenZ), these inklings of humanity help link the film to the director’s recent string of work. These films, either set in the past or, in the case of A History of Violence and Eastern Promises, bearing the scars of the past, set human pathology outside the modernity exhibited in his early work and in his typical style. Underneath its emotional detachment and spatial distortion, this is a human film, even if the humanity poised to perpetuate itself at the end does so in such a way that the ugliness of this new world may be preferable to what we have now.