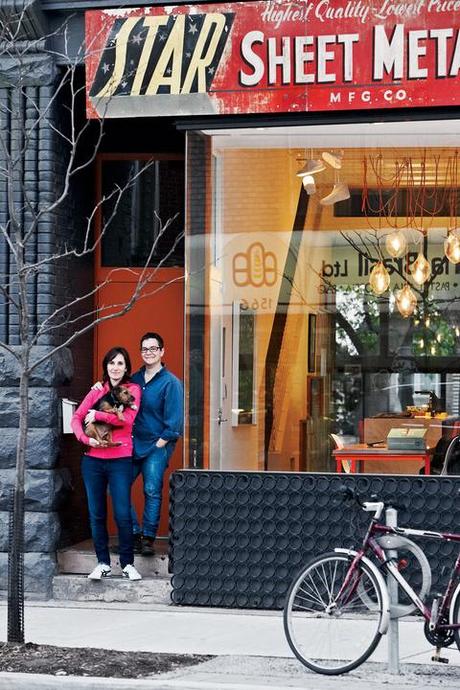

Architect Tamira Sawatzky and artist Elle Flanders get an awfully good view of their busy Toronto street from their office and dining room.

If the sign out in front of this aging Toronto facade is any indication—it reads “Star Sheet Metal”—you’d think that it’s just another industrial storefront. But when the blinds are up, you’ll see the couple who lives there making art, designing buildings, or, just as often, making dinner. The century-old structure is the home and workplace of architect Tamira Sawatzky and her wife and collaborator, artist and filmmaker Elle Flanders. In 2011, they were on the hunt for a building big enough to house themselves, their joint art practice, and individual businesses, plus an apartment for a tenant. What they found on busy Dundas Street West offered all of that—and also a chance to try a novel way of living in Canada’s biggest city.

Sawatzky: We decided we wanted a commercial building—and we wanted a space that was in the worst possible shape. This one was a complete disaster, but it had the right feel. It had the old sign, which we kept, and once we saw this room at the back, what is now the living room, I think the project sort of jelled. The building is about 75 feet long. Obviously, the office-studio was always going to go in the front, but at the back the place becomes quite quiet. When we’re back there, we don’t really hear anything. Upstairs, in a way, it’s more traditional—bedrooms and bathrooms.

Slideshow

In the second floor lounge, a Flex sleeper sofa in Gravel from CB2 sits opposite an antique Chinese coffee table Flanders inherited from her grandmother.

Flanders: Partially, this is an experiment in living right on the street. We know we’re not in Amsterdam, but it’s an interesting trial. We usually open the blinds at night and engage with what’s outside.

Sawatzky: As things progress to the weekend, we notice the evenings become noisier, and then, Sunday, everything shuts back down. You’re very in tune with the rhythms of the city here. And it’s worked well as a really social space. We’ve had way more people over—lots of impromptu get-togethers. We were giving this little talk at a gallery, which was down the street, and we said, “Everyone just come over afterward,” and they did.

Flanders: And even while we were waiting here for them, a friend of mine was going to the restaurant down the block. He knocked on the window, and then we said, “Come on in!”

Sawatzky: Everything here is long and narrow. You can’t escape that. I think it was clear right away that we were going to go with this linearity. In the kitchen, for example, I thought, Let’s load up this one island as a machine that houses everything. It has the cooktop, it has the dishwasher, the sink—and everything around it has to be left as circulation space that you can move through. It’s a huge worktop, but I feel like it was the only way to make sense of this narrow space. If we had an opportunity to open up, it was at the back, where things widen out, and we have a view and a connection to the outdoors.

Slideshow

In the kitchen, the continuous kitchen worktop and table are made of marble from Caledonia Marble. The pink Tamatik dining chairs are by Connie Chisholm and are from the Canadian design shop Made. The Blinding Love pendant lights are by Periphere, which has shops in Montreal and Toronto. The iron rails were

inspired both by screens the couple had seen on their travels in the Middle East and by the ornate wrought ironwork favored by their Portuguese neighbors. Barzel Ironworks fabricated the banister to Sawatzky’s design by slicing up iron pipe, welding it, and painting it.

Flanders: I think we’re both interested in history: not the history of this particular place, but the concept of living in a changing space. This wall has pencil notes from the guy who owned the sheet metal shop. You could just almost see Jack, this guy on the phone, going, “You want it 15 inches wide…” I like living with that kind of history in here.

Sawatzky: We were very happy to find these opportunities where we could to let the old building come through. There is a raw quality to a lot of these details. We’ve got bulbs screwed into ceramic bulb holders that are $2 each. And the ceiling is left exposed; you save a lot of money doing that, and I think we liked the idea of letting that part of the building reveal itself.

Flanders: I was hoping to find a time capsule, but we didn’t. But we did find the original shop owner’s daughter; she’s going to come over with her daughter and tell us about the building and the sheet metal business.