I didn’t get row cover on my beans in time this spring, and the flea beetles found me.

Flea beetle is something of a catch-all term used to describe several species of beetles (not all of the same genera), all of which are tiny (1/16 to 1/10 of an inch long), that live in the soil and cause mayhem in North American gardens. They adore feeding on your vegetable plants, and can reduce a favorite crop to smithereens if not dealt with promptly. One treatment won’t suffice: They can produce four generations or so in a warm-climate growing season. Overwintering adults typically emerge when temperatures hit about 50 degrees (10 C). In recent years, it’s been 50 degrees at Christmas.

Here is my quandary: Their preferred cuisine is cruciferous, which happens to be what I need to get planted soon. Most winters are mild enough here that greens and root crops may be harvested year-round if grown under horticultural fabric, but that means getting seedlings and transplants off to a good start, starting now.

Row covers can be effectively employed to exclude flea beetles from pristine soil, but (clearly) that’s not what I have. Installing row cover where an infestation has already occurred just traps the beetles inside, keeping them safe from predators while they devour your spinach. Row cover must be sealed tightly all the way around to be effective, by the way.

Trap crops come highly recommended. “Plant a crop of mustard greens!” the gardening literature exhorts. Alas, the trap crops are what I want to eat this winter. Kale, collards, mustard greens, broccolini, radishes, tatsoi, arugula. These are the seed packets sitting on my desk, awaiting my decision. I fear that planting a trap crop, even far away (relatively speaking) from the vegetable bed, will only encourage more of the little punks to move in and feast upon everything in sight.

The garden literature also recommends scouting newly planted beds and counting the beetles as they arrive. This presumes the gardener can count insects best differentiated from dirt with a hand lens before they jump to the safety of the earth. Anyone who has brushed against a plant infested with flea beetles has seen a spray of tiny bugs fleeing the scene of the crime. Who can possibly count them in situ? Even if the gardener manages to hunker silently down and get a view of the action, must she hold her breath to avoid disturbing them? What if she needs to sneeze? (It’s fall pollen season, you know.)

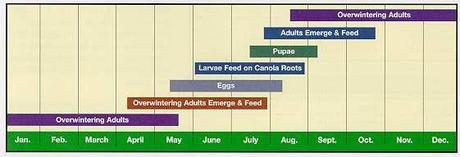

Flea Beetle Management for Canola, Rapeseed, and Mustard in the Canadian Northern Great Plains. Graphic by the Government of Saskatchewan.

I don’t want to spray if I can avoid it. I have been known to pull out the neem oil from time to time, but it’s only moderately effective against flea beetles.

What to do, then?

Possible solutions to flea beetle infestation

I’m tempted to try one or a combination of the following. Have you had success with any of these?

1. Diatomaceous earth. DE is a fine powder made of fossilized remains of diatoms, a kind of algae. When used as an insecticide, the powder absorbs components of the waxy coating of insects’ exoskeletons and causes them to dehydrate. It’s critical to obtain food-grade DE for this application to be effective.

2. Interplanting with garlic. Garlic is a moderately effective insect repellant when sprayed on plant surfaces. I have to plant my garlic somewhere; I suppose it may as well go between my rows of kale.

3. Parasitic nematodes. To read about parasitic nematodes is to discover another of Mother Nature’s horror shows. Employing them can be a bit tricky, because the gardener must get the correct kinds of nematodes (families Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae, and some species are picky about who they infect); time the application to coincide with a larval stage of the target species; and keep the soil moist, not too hot, and not too cold. On the plus side, they don’t infect birds or mammals.

Parasitic nematodes. Photo by Penn State University Extension.

Given my warm climate, and extrapolating unscientifically from the graphic above, I guess I might be able to interrupt a larval cycle if I went out tomorrow and applied the nematodes…maybe?

Please send your advice, post-haste.