What does it really mean to be conscious? To experience things? To have a self? And does that self really make choices and decisions?

What does it really mean to be conscious? To experience things? To have a self? And does that self really make choices and decisions?

I have wrestled with these issues numerous times on this blog. Recently I gave a talk, trying to pull it all together. Here is a link to the full text: http://www.fsrcoin.com/freewill.html. But here is a condensed version:

It might seem that the more neuroscience advances, the less room there is for free will. We’re told it’s actually an illusion; that even the self is an illusion. But Daniel Dennett, in 2003, wrote Freedom Evolves, arguing that we do have a kind of free will after all.

Nevertheless, the deterministic argument against free will says that everything your brain does and decides is a result of causes beyond conscious control. That if you pick chocolate over vanilla, it’s because of something that happened among your brain neurons, whose structure was shaped by your biology, your genes, by everything that happened before. Like a computer program that cannot “choose” how it behaves.

And what does the word “you” really mean? This is the problem of the self, of consciousness, entwined with the problem of free will. We all know what having a conscious self feels like. Sort of.

Another philosopher, Rene Descartes, conceived mind as something existing separately from our physical bodies. This “Cartesian dualism” is a false supernatural notion. Instead, mind and self can only be produced by (or emerge from) physical brain activity. There’s no other rational possibility.

Let’s consider how we experience vision. We not only see what’s before us, but also things we remember, or even things we imagine. All of it could be encoded (like in a computer) into 1s and 0s — zillions of them. But then how do “you” see that as a picture?

A more helpful concept is representation, applicable to all mental processing. Nothing can be experienced directly in the brain. If it’s raining it can’t be wet inside your brain. But your brain constructs a representation of the rain. Like an artist painting a scene. And how exactly does the brain do that? We’re still working on that.

Similarly, what actually happens when you experience something like eating a cookie, or having sex? The experience isn’t mainly in the mouth or genitals but in the mind. By creating (from the sensory inputs) a representation. But then how do “you” (without a homunculus) see or experience that representation? Why, of course, by means of a further representation: of yourself having that experience.

All pretty complicated. Happily, our minds — just like our computer screens — hide from us all that internal complexity and give us a smooth simplified interface.

A totally deterministic view might make our lives might seem meaningless. But Dennett writes that we live in an “atmosphere of free will” — “the enveloping, enabling, life-shaping, conceptualatmosphere of intentional action, planning and hoping and promising — and blaming, resenting, punishing and honoring.” This is all independent of whether determinism is true in some physical sense.

Determinism and causality are actually tricky concepts. If a ball is going to hit you, but you duck, would Laplace’s demon have predicted your ducking, so you were never going to be hit? In other words, whatever happens is what had to happen.

Martin Luther famously said, “Here I stand, I can do no other.” Was he denying his own free will? Could he have done otherwise? Or was his stand indeed a supreme exercise of personal will?

Jonathan Haidt, in his book The Righteous Mind, likened one’s conscious self to a rider on an elephant, which is the unconscious. We suppose the rider is the boss, directing the elephant, but it’s really the other way around. The rider’s role is just to come up with rationalizations for what the elephant wants. (This is a key factor in political opinions.)

And often we behave with no conscious thought at all. When showering, I go through an elaborate sequence of motions as if on autopilot. My conscious mind might be elsewhere. And how often have I (consciously) deliberated over whether to say a certain thing, only to hear the words pop suddenly out of my mouth?

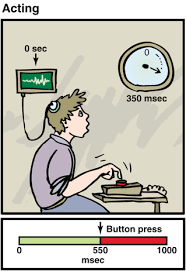

However, even if the impetus for action arises unconsciously, we can veto it. If not free will, this has been called “free won’t.” It comes from our ability to think about our thoughts.

There’s a fear that without free will, there’s no personal responsibility, destroying the moral basis of society. Illustrative was a 2012 article in The Humanist magazine arguing against punishing Anders Breivik, the Norwegian mass murderer, because the killings were caused by brain events beyond his control. But “Free won’t” is a helpful concept here. Psychologist Thomas Szasz has argued that we all have antisocial impulses, yet to act upon them crosses a behavioral line that almost everyone can control. So Breivik was capable of choosing not to kill 77 people, and can be held responsible for his choice.

As his book title suggests, Dennett maintains that evolution produced our conscious self with free will. But those were unnecessary for nearly all organisms that ever existed. As long as the right behavior was forthcoming, there was no need for it “to be experienced by any thing or anybody.” However, as the environment and behavioral challenges grow more complex, it becomes advantageous to consider alternative actions. In developing this ability, Dennett says a key role was played by communication in a social context, with back-and-forth discussion of reasons for actions, highly enhanced by language. Recall the importance of representation. I mentioned the artist and his canvas. Our minds don’t have paints, but create word pictures and metaphors, multiplying the power of representation.

Yet in Freedom Evolves, Dennett now winds up insisting that we can and do use rationality and deliberation to resolve such internal conflicts, and that “there is somebody home” (the self) after all, to take responsibility and be morally accountable. This might sound like positing a sort of homunculus in there. But let me offer my own take.

When the crewmen battle over the wheel, to say the outcome is deterministically governed by a long string of preceding causes is too simplistic.

They can change throughout one’s life, even sometimes from conscious efforts to change. And no choice or decision is ever a foregone conclusion. Even if most people, most of the time, do behave very predictably, it’s not like the chess computer that will play the same move every time. Causation is not compulsion. People are not robots.

Now, you might say the quitting itself actually has its own deterministic causes — predictable by Laplace’s demon — whatever happens is what had to happen. But this loads more weight upon the concept of determinism than it can reasonably be made to carry. In fact, there’s no amount of causation, biological or otherwise, that predicts behavior with certainty. There are just too many variables. Including the “free won’t” veto power.

And even if Libet was right, and a decision like exactly when to move your finger (or get out of bed) really is deterministically caused — how is that relevant to our choices and decisions that really matter? When in college, I’d been programmed my whole life to become a doctor. But one night I thought really hard about it and decided on law instead. Concerning a decision like that, the Libet experiment, the whole concept of determinism, tells us nothing.

This is compatibilism: a view of free will that’s actually compatible with causation and determinism.

We started with the question, how can you have free will if an omniscient God knows what you’ll do? Well, the answer is, he cannot know. But — even if God — or Laplace’s demon — could (hypothetically) predict what your self will do — so what? It’s still your self that does it. A different self would do different. And you’re responsible (at least to a considerable degree) for your self. That’s my view of free will.