Who Goes There?, by John W. Campbell Jr.

Who Goes There? is one of those books now famous(ish) because of the film that was made from it, or films I should say – in this case the 1951 science fiction horror classic The Thing from Another World!, and John Carpenter’s equally strong 1981 remake The Thing.

Most of the people who read my blog don’t care much about either science fiction or horror, which is fair enough. If you ever make exceptions though, this might be one to make, because this is something of a small masterpiece.

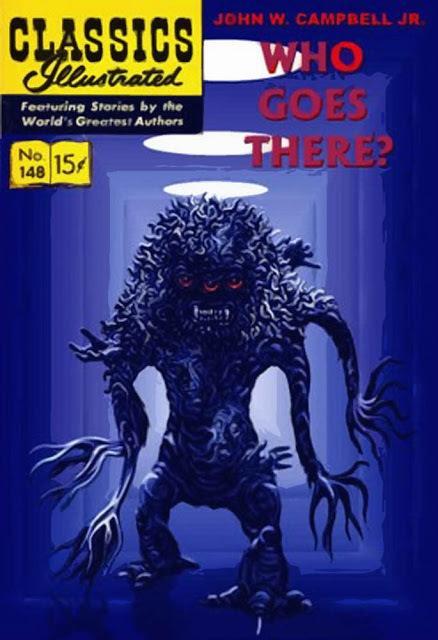

Love those old pulp covers.

An Antarctic research station find a crashed alien spaceship, ancient and entombed in ice. They accidentally destroy the ship, but they do at least recover a corpse from the ice nearby.

What follows is actually rather refreshing. The scientists at the base have an intelligent debate about whether it’s safe to thaw it out, some worried that even after 20 million years it may still harbor dangerous bacteria or viruses, the biologist Blair pointing out in return that since humans can’t catch diseases from snakes they’re hardly likely to do so from something that didn’t even evolve on our planet. Some are concerned by less tangible fears, the thing’s expression seems insane, hate-filled, and the mere sight of it causes men to recoil in revulsion. That and those who brought it back had disturbing dreams, but then who wouldn’t seeing such a thing?

Of course they decide to thaw it out, they haven’t really a choice as they know they can’t safely ship it back without it thawing mid-transit, destroying any samples they might later wish to take. They take sensible precautions though. Connant, a cosmic rays specialist, stays up with it overnight since he’ll be up monitoring equipment anyway. It’s not that anything’s expected to happen, they just want to make sure nothing goes wrong. It’s fair to say, things go wrong.

Campbell has a lovely sense of place. Here’s the opening paragraph:

THE PLACE STANK. A queer, mingled stench that only the ice-buried cabins of an Antarctic camp know, compounded of reeking human sweat, and the heavy, fish-oil stench of melted seal blubber. An overtone of liniment combated the musty smell of sweat-and-snow-drenched furs. The acrid odor of burned cooking-fat, and the animal, not-unpleasant smell of dogs, diluted by time, hung in the air.

There’s plenty of examples as good. You can feel the cold here, smell the stale sweat. Campbell establishes swiftly quite how hostile the environment is, how easy it is to get lost in a whiteout, how quickly you can freeze to death. There’s only one place here life can cling on, inside the base itself. There’s only men, dogs, and the thing which even after twenty million years is very far from dead.

The 1951 movie makes the thing a humanoid plant that feeds on blood. Hokey, but it works in the film. In the book though it’s quite different, much worse. The thing adapts, and how it adapts is by imitation. It can absorb creatures, replicate them at the cellular level, effectively become them. It doesn’t just absorb their bodies either, it takes their thoughts, their instincts – it’s telepathic, making it the perfect mimic.

What that means is that anything it can reach it can infect, take over. Dog, gull, seal, whale, it doesn’t matter. Anything it can reach it can become. Anything it becomes ceases to be what it was, is now a vessel for the thing, and it remembers every form it’s ever taken. If it gets out it’s literally the end of the world. It gets to the dogs, it starts to become a dog, but the barking of the rest of the pack alerts the men of the base and they find it mid-transformation, kill it with electrical cables. They consider what they’ve seen:

“… It can imitate anything – that is, become anything. If it had reached the Antarctic sea, it would have become a seal, maybe two seals. They might have attacked a killer whale, and become either killers, or a herd of seals. Or maybe it would have caught an albatross, or a skua gull, and flown to South America.”

It’s dead though, they think. Dr. Copper starts to reflect how lucky they were, though Blair quickly corrects him:

“Then we can only give thanks that this is Antarctica, where there is not one, single, solitary, living thing for it to imitate, except these animals in camp.” “Us,” Blair giggled. “It can imitate us. Dogs can’t make four hundred miles to the sea; there’s no food. There aren’t any skua gulls to imitate at this season. There aren’t any penguins this far inland. There’s nothing that can reach the sea from this point—except us. We’ve got brains. We can do it. Don’t you see—it’s got to imitate us—it’s got to be one of us—that’s the only way it can fly an airplane——fly a plane for two hours, and rule—be—all Earth’s inhabitants. A world for the taking—if it imitates us!

That’s where the real horror starts. They killed it, yes, but what if they killed it too late? What if it’s already infected one of them? Assumed a man’s form, copied his mind, is waiting among them for the snows to lift and for them all to be taken home, where it can spread and colonise? Connant spent the whole night with the thing, is he still Connant? Who else might it have got to? It could be anyone, it could be several of them, all they know is that it can’t be most of them since if it were it wouldn’t bother hiding any more.

What follows is probably the most chillingly paranoiac novel I’ve yet read. There were times I had to close it just because the claustrophobia was too strong, the sense of dread and isolation. The radio’s quickly smashed so as to stop the thing calling for an emergency airlift out, but time’s passing and with it the season. Eventually the relief crews will come, birds will start to pass overhead again, all it has to do is wait, pretending to be one of them, pretending to be just as afraid as everyone else.

I won’t say much more about what happens, I don’t really need to – you can probably imagine. They develop a test to distinguish between someone who’s still human and someone who just seems human, but who do you trust to administer it? If a man refuses to let the person with the test near them does that mean they’re a monster, or that they’re human and don’t know if the person doing the testing is a monster? Every man is trapped in his own solipsistic hell, except of course that’s not true because some of them aren’t men anymore.

There’s not a lot else to say other than that this really is a quite brilliant little novella. Obviously if you’ve no patience for pulp tales of alien horrors from beyond the stars it’s not for you, but if you can swallow that part what follows is intensely evocative, so much so that I was glad it was short and I could come out of it blinking in the summer sunlight, if still feeling slightly cold. I don’t know if it’ll make my end of year list yet, but it’s a definite candidate. A wonderfully chilling little tale, and golden age science fiction at its best.

Filed under: Campbell Jr., John W., Horror Fiction, Novellas, Science Fiction Tagged: John W. Campbell