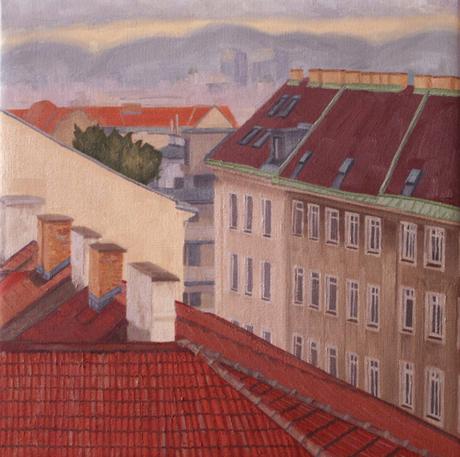

Wien funkelt © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

I’ve spent some time lately in the galleries trying to come to an understanding about composition. Not really knowing what I was looking for, I took my sketchbook and pencil and set about collecting some information, reducing it, simplifying it, hoping to see some sort of pattern emerge. In fact, many different patterns emerged from my little thumbnails.

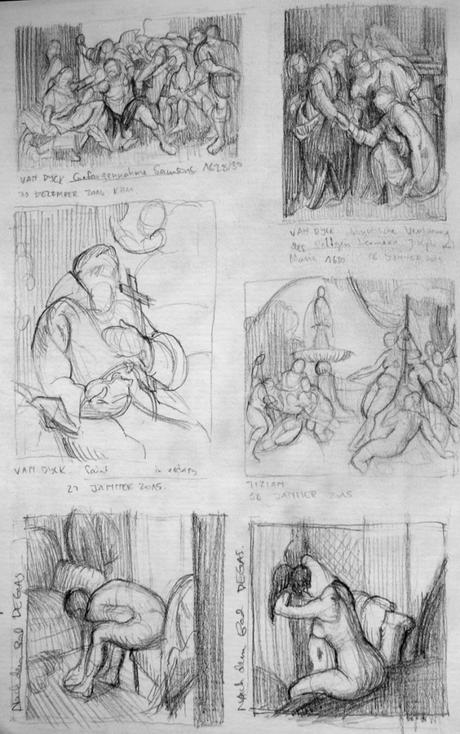

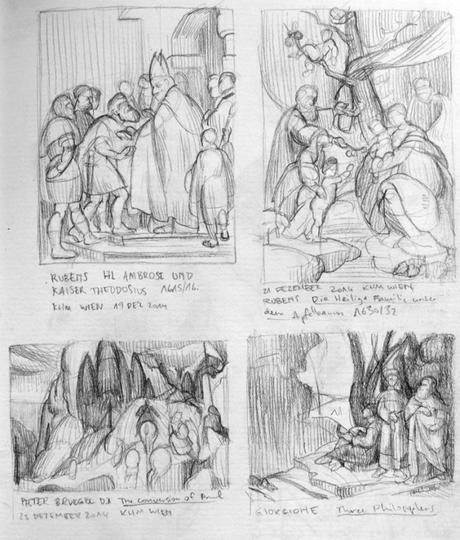

In Van Dyck’s Gefangennahme Samsons (1628/30) the heavy weave of the fabric of the painting showed a tightly constructed image, the whole picture electrified with energy and motion, though the frenzy offers no relief for the eye. His Mystische Verlobung des Heiligen Hermann Joseph mit Maria (1630) concentrates the action into a similarly dense knot, with figures and drapery tangling together, but the rhythms run three-dimensionally, not confined to the flat pictorial space. An oval slopes deep into the picture, running through the loop of arms at the centre. Similar retreating ovals swing through Rubens’ Heilige Ambrose und Kaiser Theodosius (1615/16) and Die Heilige Familie unter dem Apfelbaum (1630/32), intersecting with the two-dimensional arrangement.

Titian’s Diana revealed complex braids of arcs through the dizzyingly busy picture. Actually each curve is a wonderfully simplified statement that seems to keep the picture in motion, a liquid in suspension, not snagged by unnecessary points of elbows or knees. And Degas blares out as the most unselfconsciously shape-loving painter, with his charmingly intimate square pastels, both Nach dem Bad, almost pieced together from strong, insistent shapes rather than representations of interiors. And yet, despite the prominence of these shapes, Degas never relinquishes the fullness of forms.

While these investigations turned up some interesting ideas, the jumble of thoughts they produced in my mind left me no clearer of how I ought to approach composition. And despite the importance of concrete examples, I was looking for a more unifying, fundamental way to grasp the concept. It was at this point I returned to Robert Nelson.

The main point to hold in your mind when thinking about composition is that it is, at heart, about construction. You’ll forgive my constant sideways remarks about photography, but our aesthetic vision is currently somewhat obscured by the lens, and in the matter of composition, by the viewfinder. ‘Photography as a process, certainly in its documentary incarnations, might be described as a roving rectangle in search of a motif,’ writes Nelson (2010: 99), continuing sympathetically but firmly, ‘The nomadic and scavenging character of documentary photography makes for an art of great complexity; but it is essentially different from the constructed technologies of the past.’ As a painter, I know my own understanding of composition was clouded by this idea of finding and framing. Yet the painter suffers no such constraints: she is at complete liberty to compose, exactly as the musician may draw notes from his mind and not wait to capture them. Dewey (1934: 75) compares it to the ordering of thoughts of the writer: ‘As the painter places pigment upon the canvas, or imagines it placed there, his ideas and feeling are also ordered. As the writer composes in his medium of words what he wants to say, his idea takes on for himself perceptible form.’

Nelson (2010: 95-6) argues that, despite the popularity of the idea, there are no ‘design principles,’ no rules to be taught, no natural laws to transform aesthetics into a science. Conventions of the past were simply that—conventions, not eternal ideals. Golden means and overlaid geometry reek of ‘numerological witchcraft’ to him. Yet composition remains vital to painting because of the deliberateness it entails. The painter actively arranges not only elements, but space and even, he (2010: 98) argues, ‘the way that you encounter the motif.’ The whole is a carefully contrived experience, deliberately built up from nothing.

Rather than groping fruitlessly after scientific justifications for the success of compositions, Nelson (2010: 96) suggests turning to the poetic. Composition, far from submitting to rules, is rather a matter of expression, and perhaps even, as Dewey suggests, of emotion. Dewey (1934: 70) writes of the deliberate arrangement of the whole: ‘The determination of the mot juste, of the right incident in the right place, of exquisiteness of proportion, of the precise tone, hue, and shade that helps unify the whole while it defines a part, is accomplished by emotion.’ The painter has complete control over how the stage is to be set, over how the experience is to unfold. The balance or imbalance is completely at her disposal; the weight of the tones may set the mood she desires, the space may be moulded or the shapes emphasised or the rhythms interlaced as best suits her own expressive purpose. Dewey (1934: 62) is quick to clarify, however, that this expression, however emotional, remains calculated and controlled:

‘To discharge is to get rid of, to dismiss; to express is to stay by, to carry forward in development, to work out to completion. A gush of tears may bring relief, a spasm of destruction may give outlet to inward rage. But where there is no administration of objective conditions, no shaping of materials in the interest of embodying the excitement, there is no expression. What is sometimes called an act of self-expression might better be termed one of self-exposure; it discloses character—or lack of character—to others. In itself, it is only a spewing forth.’

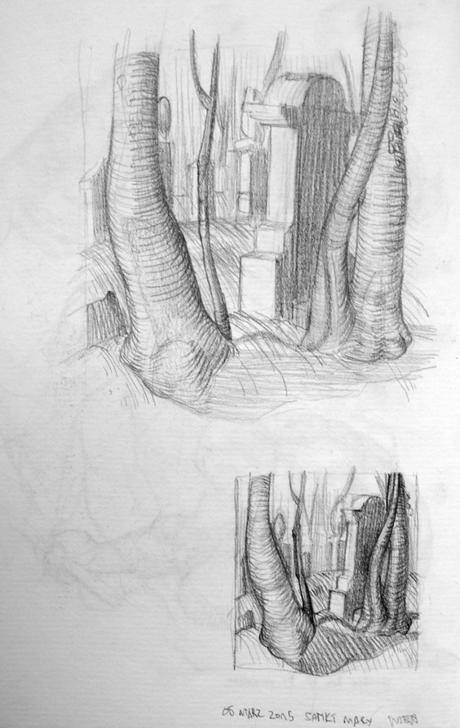

In order to express something clearly, to honestly transcribe emotive experiences, the painter must keep the whole before her, and work in a flexible way. Her medium needs to be pliant enough to push around, to adjust, to exaggerate, to search out (Gombrich 1996: 214). Drawing is the most obvious starting place, offering a reductive description, a non-committal, experimental visualisation of the unborn painting. Without labouring details, the painter can think through the unity of the whole and observe the interaction of the ill-defined parts. She can crop and re-crop. She can design, she can grow the image organically. In keeping the whole at the fore, she can keep the emotional experience tight and true. Da Vinci (in Gombrich 1996: 213) confirms this fluid mode of working and the connection between emotion and composition in both his hairy drawings and his writings:

‘Now have you never thought about how poets compose their verse? They do not trouble to trace beautiful letters nor do they mind crossing out several lines so as to make them better. So, painter, rough out the arrangement of the limbs of your figures and first attend to the movements appropriate to the mental state of the creatures that make up your pictures rather than to the beauty and perfection of their parts.’

I expect I’ll continue to collect thumbnails at the gallery, but with renewed purpose: There are no codes to decipher and assimilate, no universal truths to unearth. There is only the deliberate hanging-together of the whole—directed by the emotional impulse of the author—to unravel and to admire. And my own emotional intent to orchestrate in my own paintings, beginning with my ever-pliable pencil.

Dewey, John. 1934. Art as experience. Minton, Malch & Company: New York.

Gombrich, E. H. 1996. The essential Gombrich: Selected writings on art and culture. Ed. Richard Woodfield. Phaidon: London.

Nelson, Robert. 2010. The visual language of painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique. Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne.