Literary action isn’t like that. To be sure, until you’ve read, say, Pride and Prejudice, you didn’t know anything about this imaginary family, the Bennetts, and their imaginary relatives and acquaintances. But purpose of the narrative is not primarily to inform you about those imaginary people and events. It is something else. What that something else is, well that’s something of a puzzle. And I want to push most of that puzzle to the side for the moment.

In this post I want to present some simple diagrams and use them to say a bit about how I think about literary interaction and then make a few observations about naturalist and ethnical criticism.

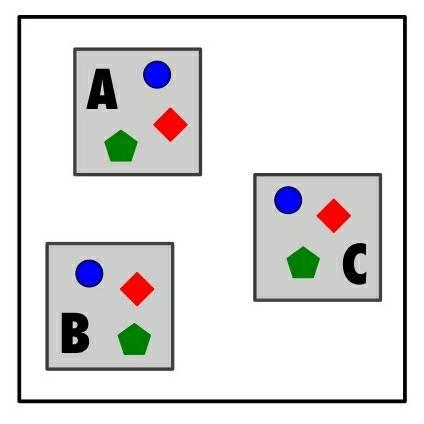

In the diagram below I have three highly abstracted and stylized individuals, A, B, and C. The red, blue, and green objects represent things in their brains, each might be a specific brain region, or a bundle of fibers, or perhaps a connected set of synapses, whatever. Each brain will in fact contains 100s of 1000s of such things.

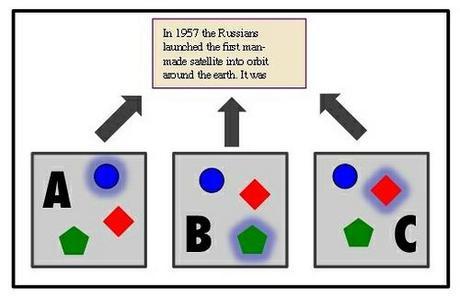

In the next diagram we see the three individuals reading the same text. While they might be in the same place at the same time and so be reading off the same physical text, that’s not necessary. They could just as easily be reading different instances of the same text at different times and in different places.

In the next diagram we see the three individuals reading the same text. While they might be in the same place at the same time and so be reading off the same physical text, that’s not necessary. They could just as easily be reading different instances of the same text at different times and in different places.

The point of the diagram is in the “auras” that some of the objects have and others do not. Those are not the same for the A, B, and C despite the fact that they are reading the same text. There’s nothing about the text that constrains them in the same way.

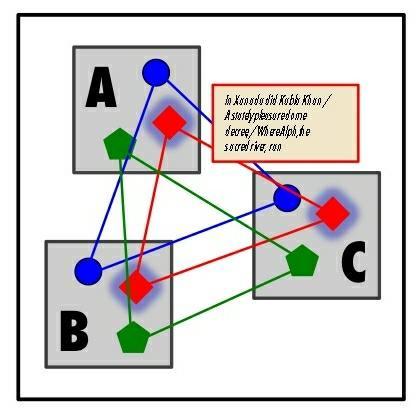

That’s not how literary texts work. The simplest case is that of oral story telling, where the storyteller and audience are co-present. In that situation, I have argued in various posts, all of them are coupled into a single physical system, like so:

Most of the signal paths are electro-chemical and exist inside brains; but some of them are mechanical – vibrations in the air – and connect brains with one another. They are coupled. But the coupling doesn’t take place through a solid physical connection, like a socket, rather it is the text that serves as the medium of coupling. The coupling is virtual.

Most of the signal paths are electro-chemical and exist inside brains; but some of them are mechanical – vibrations in the air – and connect brains with one another. They are coupled. But the coupling doesn’t take place through a solid physical connection, like a socket, rather it is the text that serves as the medium of coupling. The coupling is virtual. In coupled brains the same neural systems are activated at the same time, as indicated in the diagram. And in the case of oral story telling the stories contain no new information. The same stories are told time and again, year after year, generation after generation. For any given individual there will be a first time they hear the story and, several repetitions later, there will be a time by which all of the characters and incidents are familiar. Yet the story still retains its interest. There is nothing new being conveyed from storyteller to listener.

Rather everyone present is sharing in the event of the story telling. The storyteller plays one role; the listeners play another. But the situation as a whole is one of sharing and participation, not of conveying new information.

Of course, things change a bit with written texts. Authors do not necessarily know readers, readers do not know one another, and so forth. The physical connection that exists in oral story telling isn’t there. But, I will simply assert, the logic of the situation remains the same. That, I know, requires an argument, or rather, a construction, but I want to skip that at the moment.

I want make a few remarks about criticism. Basically, the ethnical critic is concerned to intervene in the coupling connecting readers and authors while the naturalist critic remains outside the circuit, observing it for the purpose of understanding how it operates. Because the coupling IS virtual and not “hard-wired” it is in a significant degree subject to persuasion. One can learn to like certain texts that might first seem off-putting for some reason and one can learn to dislike others that are initially attractive.

While I talk of ethical and naturalist criticism as two different activities, they are certainly activities that one and the same individual can undertake. In that sense perhaps we should think of ethical and naturalist stances. Ethical criticism, in this sense, has always been possible and has always existed, if only in casual remarks about likes and dislikes. Naturalist criticism is another matter. One’s ability to stand outside the coupling circuit depends on having the conceptual tools to do so, concepts about language, cognition, the brain, and so forth.

One question facing the profession, it seems to me, is whether or not we now have the tools we need to claim new ground for the naturalist stance, ground that was just barely visible to Northrup Frye when his Anatomy of Criticism was published six decades ago. A correlative question, of course, is whether or not the profession can openly embrace its ethical function.