So that’s the way it is. Comanches kill Mexicans to get even with the Spanish. And the Mexicans kill Comanche in revenge for that. It’s become a way of life.

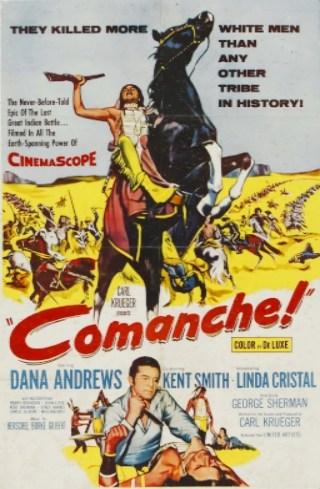

Westerns, naturally enough, have a habit of featuring a fair number of real life historical figures. For the most part, these portrayals are heavily fictionalized since the films are dramas first and foremost. We’ve seen outlaws and lawmen, soldiers and natives transposed to the big screen, and it’s those in the latter category who, despite what some might tell you, actually tend to fare best in terms of sympathetic depictions. Comanche (1956) looks at Quanah Parker, the son of a captive woman, who rose to prominence as a war chief among his tribe, and presents him in a highly flattering light.

The onscreen prologue informs us that in 1875 a bitter and age-old war continues to rage between the Mexicans and the Comanche. The latter raid and massacre the unprotected villages close to the frontier with the US with impunity, while the former still pay out a bounty for Comanche scalps. The result is a brisk trade among the despised scalp-hunters and also pressure from the Mexican government on their northern counterparts to do something about the frequent cross border incursions. The opening sees one of those sleepy villages razed to the ground, its inhabitants largely butchered and the young women taken as captives. The scene then shifts to the land just across the Rio Grande, where part of the raiding party stumble upon a team of scalp-hunters and quickly overpower them. Just as the prisoners are about to be roasted alive, their grisly death is halted by the intervention of a more powerful presence. This is Quanah (Kent Smith), and his actions serve to raise the ire of his subordinate Black Cloud (Henry Brandon) and also to raise questions in the viewer’s mind. Why should this man make such a magnanimous gesture towards those preying on his people and simultaneously risk alienating the more hot-headed types like Black Cloud? The army’s chief scout Jim Read (Dana Andrews) has a hunch it’s a means of sending out signals of peace. When the US and Mexican governments decide to act, it’s Read who suggests heading into Comanche territory to sound out Quanah on his intentions, and maybe open negotiations with him instead of going straight for the military option. We later discover that there’s an intriguing connection between these two men, although both will have to address betrayals from within their own ranks by those with hawkish tendencies if any rapprochement is to be achieved.

What can be termed pro-Indian sentiments are to be found scattered throughout the westerns of the 1950s, and Comanche is yet another example of this trend. Part of the beauty of these movies, for me anyway, is the realistic way this is handled. We’re not presented with some blind diatribe, demonizing one side or the other for the sake of cheap point scoring. Instead, by focusing on a few individuals, there’s a more balanced perspective offered – the rights and wrongs, along with the brutality and cruelty perpetrated by both camps is acknowledged and confronted. As with almost everything in life, it’s only through such consideration of the subtle shadings that a mature appreciation is possible. And remember, it can’t be stated often enough that the 1950s was the decade when the western itself attained full maturity as a cinematic art form.

Comanche was directed by one of this site’s favorites, George Sherman. He was no stranger to the pro-Indian western and his strong visual sensibility is always in evidence too. This is very much an outdoors picture, shot by Jorge Stahl around Durango, and the tough, dusty landscape provides a harsh and bleak canvas upon which the human drama is played out. Sherman frequently makes full use of the wide scope lens, that primal backdrop packed with hordes of Comanche warriors or snaking columns of cavalry, to create an epic feel at times.

The character of the cavalry scout is a pivotal one from the audience’s point of view as the impartial intermediary acts as the eyes through which we view the unfolding events. Such a role needs to be filled by a man who can convey a sense of integrity alongside a stoic quality, yet he must also maintain an air of the outsider about him since he’s essentially got a foot in both camps. Step forward Dana Andrews. If ever an actor was possessed of the aforementioned characteristics, then it must surely be Andrews. He’s obviously best known for his noir parts, particularly those with Preminger and Lang, but he was equally fine in the western too. Kent Smith might seem like an odd choice to play Quanah, still I think he’s satisfactory. You could argue his role is a touch too noble and one-dimensional, I suppose; even so, he invests the part with a great deal of dignity and you get a feeling of the power of the character. The villainous types are played by Henry Brandon (interestingly taking on the part of the enemy of his own son, if you read The Searchers as a loose adaptation of the Parker story), Stacy Harris and Lowell Gilmore. And then there’s the beautiful Linda Cristal, making her Hollywood debut as the traumatized captive girl. She is pretty good although her character doesn’t get quite as much development as it deserves. Anyway, Sherman was obviously sufficiently impressed by her talents to use her again as the female lead in The Last of the Fast Guns a couple of years later.

Comanche has been available on DVD in France and Spain for a while now but I held off buying it as it seemed the picture quality was nothing special and then there was also the forced subtitle issue on the French disc. It’s just been released in the UK by 101 Films, who have put out a number of western title in recent times, and so I thought I’d take a chance. First, the good news: the film is presented in its correct 2.35:1 scope ratio. And now for the bad news: the disc is not anamorphic so the image is surrounded by heavy black bars that can only be reduced by zooming in, with the resultant loss of resolution. Also, the print used is clearly an old one which, although not showing all that much damage, is somewhat faded and lacking in detail. All told, it’s a very disappointing presentation of the film, one which I can’t recommend in good faith. What makes this even more frustrating is the fact that the film itself is a very worthwhile one that deserves far better treatment than it’s been afforded so far.

By way of a postscript, I’d like to add that this blog was eight years old a few days ago. Normally, I like to mark the occasion with a posting but circumstances conspired against me this time. Anyway, I reckon this movie is an appropriate way to celebrate the anniversary, albeit a couple of days late.