This article was first published on Voice4Change England (3rd February 2015)

This article was first published on Voice4Change England (3rd February 2015)

Coloured, half-caste, half-breed, mulatto and mongrel. These and many other insulting labels have been stapled to people like me, a black man of mixed African and English heritage.

“Does it matter if [the actor Benedict] Cumberbatch used the wrong word?” asked Ben Andrew in an article on this site. Well, it does if you have been on the receiving end.

Andrew went on to claim that “the word coloured is, of course, a deeply offensive term in the United States – much more so than it is in the United Kingdom.” I assume he is basing that statement on research rather than personal experience. Reading his article, as someone who has suffered such insults, I felt moved to add some historical context, and a bit of that personal experience too.

Words matter because it frames our identity and our world, our beliefs and feelings, and sets the boundaries for respect and disrespect, equality and prejudice, oppression and freedom.

Ideas matter too, which was the point David Oyelowo was making when he ‘defended’ Cumberbatch. Oyelowo was somewhat misrepresented by Andrew; the Selma actor did not in any way dignify the word, he merely said that reaction to Cumberbatch was diverting attention from the point he was actually making – namely that black actors faced racism in the industry. Oyelowo was saying this diversion was “ridiculous”, not anger at the use of the word.

Of course words and ideas overlap, as Yemisi Adegoke pointed out in The Independent. She said:

“The word “coloured” is offensive because it removes an element of humanity from people. Ribena is coloured, walls are coloured, people may be of color but they are not coloured. It also harks back to the racist notion that being white is the default state and everyone else is “other,” an aberration from the norm.”

I am deeply uncomfortable with people who are not black proclaiming what terms are or are not acceptable or offensive. Self-determination is one of the foundations of the road to mental emancipation.

Terms to describe us are often a topic of debate. Ethnic minority, BME, BAME, Black, African, Afrikan. It is a constant process of questioning labels imposed from others and mulling over the terms we apply to ourselves, and how we think about ourselves. But more importantly it is what such terms say about us, our identity and consciousness, the tensions between integration, assimilation and the freedom to be. And between the expression of culture – modern and historical – and appearance, pride in self and the very essence of working together as ‘a community’.

There are any numbers of ‘shades’ of opinion on all these questions. There always is. Divide and rule wouldn’t work without it.

In southern Africa, ‘coloureds’ were encouraged by the apartheid systems to see themselves as a separate community; above the ‘blacks’. They received a slightly better education and took jobs as supervisors carrying out the white rulers’ wishes. From the Cape Coloureds of South Africa to the coloureds of Arcadia in Zimbabwe, they knew their place in the hierarchy – one below Indian but significantly above the majority black population. And they were happy to remain there.

Many coloureds descend from the Khoi-San people and owe their light skin to systematic rape by the white settlers from Holland, England and other Europeans. Most of African-Americans and Caribbean’s went through this experience throughout chattel enslavement as slave ‘owners’ bred slaves.

The Boers invented a bewildering number of racial categories, with hundreds being reclassified from one category to another with each census. All to keep a hierarchy in place, with whites at the top.

A similar system existed in Brazil, where there were no less than 134 categories including Alva (pure white), Avermelhada (reddish with blood vessels showing through the skin), Canela (cinnamon), Castanha (cashew) and Cor-de-cuia (tint of coffee). Even today, Brazilians still use a plethora of common descriptions for skin colour, including mocha and cinnamon.

Brazil remains a deeply racially divided society with the favelas overwhelmingly populated by the darker-skinned, as in South Africa where many coloureds still believe they are superior. Wherever whites have ruled, including the Caribbean, the legacy of racial hierarchies persists as a drag on the journey towards equality. The plague of shadism is still very much with us today.

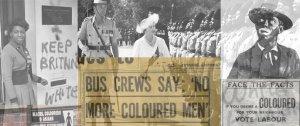

In Britain, the word ‘coloured’ was in popular use until the 1970s, usually as a more polite term compared to nigger, wog or coon. As a consequence some older black people who lived through this period still use it. But it remains a word associated with a period when racial abuse was rife and violent racial attacks more common. An era of the golliwog and Teddy Boys, of ‘white power’ graffiti and of rivers of blood.

It was 1968 when James Brown released ‘Say It Loud, I’m Black and Proud’. In the 1970s lovers rock artists like Brown Sugar responded with seminal tracks like ‘Black Pride’. The movement to reclaim the word ‘black’, so long used in a derogatory fashion, had triumphed. There was no such effort to reclaim the word coloured.

So when, in 2005, the then chair of the Commission for Racial Equality, Trevor Phillips, claimed that it was acceptable to use the word coloured he was understandably met with a barrage of criticism from anti-racist campaigners. We want to go forward, not back, his critics said. Let bygones be bygones.

Some older folk may still cling to the word like they are cuddling a golliwog doll but in the 21st Century, several generations after the sun set on the Empire, there is no need to turn the clock back when there is so much left to do to tackle casual and institutional racism in society.

In some ways Phillips seems to be applying the same arguments as Andrew; what’s in a word? Surely it’s not that offensive? Not nearly as over there in the United States? If someone like Cumberbatch means well, give them a break.

Yet words define ideas. They defined enslavement and apartheid, encapsulated the struggle of the Windrush generation settling in a hostile environment, and they are the building bricks of progress. The words of identity provide the confidence to speak for ourselves, on our own terms, through our own eyes, conveying our own varied experiences as individuals and as a collective through what unites us.

Growing up in the 1970s and 80s I experienced many racially abuse terms throughout the period of primary and secondary school. I’ve been called a nigger and a half-caste. Chocolate and caramel. The word black has been spat at me as an insult, the word yellow in jest. Through the eyes of others I’ve been a mixture of black and coloured all my life, but never white. And, interestingly, never African even though my mother is just that.

Whatever the varying degrees of good or bad intentions behind these words, on one level they are all interchangeable. They all say one thing; I stand out, I am different. For some, a lifetime of exposure to these various words ultimately creates layers of fear of being too different, too black, too African. If I’m coloured, as defined by others, let me accept my place in the hierarchy. After all, it’s not too bad, is it? At least it’s better than being a nigger or a mongrel.

Yet if enough black people accept our place in society, the media and the film world, we are left with no choice but to accept the likes of Cumberbatch speaking on behalf of black actors rather than black actors speaking for themselves, however clumsily they do it.

So does it matter if Cumberbatch used the wrong word? It does if we still live in the wrong world.