A recent library visit found me as usual scanning the ‘New Titles’ and ‘Just Returned’ shelves for any likely contenders for a bedside table slot. Sometimes I have a deal with myself that I won’t take yet another book home (to distract me from the TBR Pile) if I can get out of the building without anything on the two aforementioned shelves catching my eye. Well, dear reader, as is so often the case something did catch my eye, thus pushing another book back a notch in the reading order. I should really ban myself from libraries until I have nothing left to read on The Landing.

Anyway…

The Zhivago Affair by Peter Finn and Petra Couvée was the title that grabbed my attention and threatened the status of the bedside table pile. The subtitle: The Kremlin, the CIA and the Battle over a Forbidden Book at first made me assume that the book was fiction. It sounded like a literary caper that would be right up my street. As it happens, the book is a real life literary caper that indeed proved to be right up my street. One of those ‘the truth is stranger than fiction’ or you ‘couldn’t make it up’ reading experiences. It really was like reading a Cold War spy novel but with added poetical asides and royalty disagreements to add piquancy.

My library find…

Finn and Couvée’s book tells the story of the battle to get Doctor Zhivago published and in particular reveals the CIA involvement in publishing and distributing a Russian language edition in 1958. As might be supposed, the CIA involvement had as much, if not more to do with propaganda than literature. According to one of Pasternak’s sons, Yevgeni, the author wasn’t at all happy about his work being used for Cold War propaganda purposes. Over the course of several years of research, Finn and Couvée uncovered the complicated saga of Doctor Zhivago with the help of previously classified CIA files. I could not help feeling that releasing the files was in itself yet another propaganda act. This is the CIA saying, ‘look it’s not all guns, we’re really nice guys and we love culture, and books and stuff’. It’s hard to judge whether the people in the organisation actually cared about the book or Pasternak, or whether they just cynically used a golden opportunity to poke the USSR. In these days of Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, the idea of a novel being such a powerful propaganda tool may seem quaint but it truly was that important in the West’s campaign against Communist ideology.

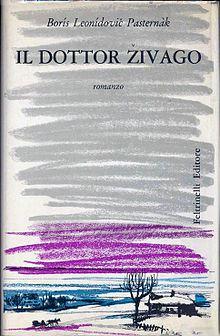

As you might recall, I read Pasternak’s book last year, many years after I first saw the film version and fell in love with Omar Sharif and the wonderful Russian scenery (which of course wasn’t Russian at all). The first edition of Doctor Zhivago was published in 1957 in Italy, as Pasternak was unable to get his first and only novel published in his own country. Pasternak told Italian publishing agent Sergio D’Angelo that ‘In the USSR, the novel will not come out. It doesn’t conform to official cultural guidelines’. Literature was very important in Soviet Russia, however the chilling fact was that it had to be the correct sort, as was made clear by Stalin in a 1932 speech at a gathering of writers to launch the ‘new literature’,

The production of souls is more important than the production of tanks…Here someone said that a writer must not sit still, that a writer must know the life of a country. And that is correct. Man is remade by life itself. But you, too, will assist in remaking his souls. This is important, the production of souls. And that is why I raise my glass to you, writers, the engineers of the human soul.

Italian First Edition

If Golslitizdat, the state literary publisher did not consider a writer’s work suitable (not sufficiently productive of souls), then it would not see the light of day. There may also be serious consequences for the unfortunate author, despite the apparent thaw since Stalin’s death. As Doctor Zhivago had no merit in the eyes of the state publisher, Pasternak’s manuscript was smuggled out of Russia by D’Angelo. He was acting on behalf of Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, a Milanese publisher (a member of the Italian Communist party). Pasternak handed the manuscript over knowing that he was potentially putting his life at risk, as well as those of his family. He rather theatrically said to D’Angelo, ‘You are hereby invited to my execution’ after handing over his work with the words ‘This is Doctor Zhivago. May it make its way around the world’. I wonder if he had rehearsed those lines?

Having read the book, I would now like to read a straightforward biography of Pasternak, as this book obviously focuses on the Zhivago story. From what I have gleaned from this book, Boris Pasternak’s character was contradictory and he was probably not the easiest person to live with (whether his second wife Zinaida or his lover Olga). He had an unshakeable belief in his own talents yet was also unassuming, modest and personally engaging. It is hard to get to grips with, and understand Pasternak’s character. He seems to have been selfish enough to pursue publication even knowing that it could rebound badly upon his family. In fact, his mistress Olga Ivinskaya was twice imprisoned for her part in the affair, the second time after his death in 1960. Yet, according to the evidence, Pasternak was courageous enough to support the family members of those writers sent to the Gulag when others kept a distance.

Reading The Zhivago Affair has given me more leads to follow, not only on discovering more about Pasternak and his family but also about other writers mentioned in the text such as Osip Mandelstam and Anna Akhmatova. One book that I did read a few years ago was a fictionalised account of Isaac Babel’s imprisonment in the Lubyanka, The Archivist by Travis Holland which I would highly recommend. It’s not a happy read as you might expect, but there is still a bit of hope for humanity and the written word in it. Which brings us back to Pasternak’s work making its way around the world despite the repressive regime under which he lived.

If anyone has got any related recommendations, I would love to hear them…

Picture credit for the Italian First Edition : Wikipedia, with thanks.