Cloud Atlas: A Review

A lot of lip service was given to how difficult Cloud Atlas, a novel by David Mitchell, was to adapt into a film. It was the hook that drove publicity. Unlike most people in the film industry, however, I read the book, which from my memory, lent itself well to the cinema. It’s very episodic. It’s also not that long—400 pages or so. Let’s just say that Mitchell is no fucking George R.R. Martin, and George R.R. Martin got a fucking 10 episode television series. This introduction sucks, but I don’t feel like re-writing the post to make it better, so you’re going to have to deal with it.

What I mean to say is that I don’t think the book could have been THAT difficult to make into a film. But I’m probably wrong. To save you from the agony of having to make the decision for yourself, I’m going to start by describing the book, and then give an idiotic synopsis of the film. Let us begin.

Cloud Atlas opens in a past time—the 19th century, to be exact—with the tale of a sailor, Adam Ewing, a man who would be an abolitionist if his father-in-law was not a slave dealer, who writes a fever journal as he travels back to San Francisco from the Pacific Islands. His tale is followed by five others, all starring different narrators, in different times.

They include Robert Frobisher, a dandy, a reprobate, and a brilliant composer in pre-World War II Belgium who the most beautiful symphony ever heard by all the other characters in the novel.

Luisa Rey, an investigative journalist in the 1970s who uncovers the evil plot to cover up the dangers of a nuclear power plant on the verge of exploding.

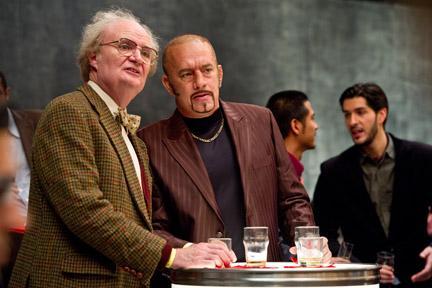

Timothy Cavendish, a British vanity publisher in contemporary times, no doubt one with horrific breath, who is forcefully committed to a nursing home by his gangster of a brother.

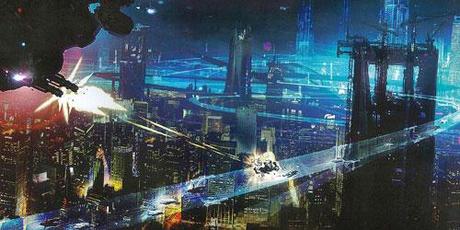

Sonmi~451, a human clone living in a dystopic, futuristic Seoul, Korea.

And Zachry, a man living hundreds of years after “The Fall,” some kind of post-nuclear horror event that leaves the world flooded, and survivors marooned on high-tech ships or tiny islands full of cannibals. This is clearly my favorite part of the book.

The book unfolds chronologically, each story nested in the next story as a fictional tale being read by the main character in the future. It crescendos with Zachry’s unbroken narrative, and then retreats back into the past. If you imagine a novel as a bell curve, or a pyramid, or a musical scale—the chapters build on one another, are capped by Zachry’s narrative, and then retreat, counter-chronologically, to the first story—then you’ll get a sense of how Cloud Atlas is organized.

The structure allows Mitchell to build suspense, and then leave the reader dangling, tearing through pages to see what happens. It also allows him to build connections between each character that are revealed both in the future, and in the past, as characters look both forward and back.

Mitchell has an incredible facility with the English language; each story is written in the voice of its narrator, who speaks in a dialect—whether real or imagined—that is specific to their time. He can be quite difficult to read—I personally didn’t really get into the book until Sonmi~451 showed up, and that’s only because I live for a post-apocalyptic stories.

Although connections exist between characters—Sonmi, for instance, is worshipped as a goddess by Zachry—they are not always readily available to the reader. They aren’t obvious; they are tenuous. They read like deja vu rather than clues to resolve a mystery.

Having given that synopsis of the book, it probably seems obvious why it was difficult to make it into a film. I’m getting kind of bored of this post (aren’t you?). Too thoughtful. So I’m going to let go of language Brie-blog-style, and describe the film all loose-like. You might not notice a difference, but I will. Here’s where I take-off.

So, the film was created, directed, written, and mostly funded by Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run), and Andy and Lana Wachowski (The Matrix). Lana used to be Larry Wachowski, but she had a sex change. Now, she makes for a very, very strange looking, but also arresting, woman.

They break the structure of the novel, building their narrative in snippets of action that rapidly jump time periods, revealing connections between characters. The entire film has an overarching theme of “what you do in the past affects the future, and also soul mates are for real.”

The book would have made a killer, but perhaps slightly empty, television series; as a movie, it runs at 3 hours. Even though the film seems derivative of each respective directors earlier work —Sonmi’s world is like The Matrix Redux, the scenes starring Luisa Rey are like “Run, Luisa Rey, Run”; even though it can be, as you might suspect, a tad maudlin; even though it stars Tom Hanks; it is entirely satisfying. I did not check my phone a single time in the entire three hours, and I did not use a semicolon correctly a single time in the previous sentence.

Tykwer and Wachowski apparently fell madly in love with the novel—their devotion to it shows in the film. That is an empty thought, but I drank a fair amount last night, so cleverness is eluding me.

What I mean to say, I think, is that even though the starring actors and actresses—Jim Broadbent, Hugo Weaving, Jim Sturgess (just fyi, I have no idea who any of these guys are, I’m just listing them from the IMDB page), Doona Bae (a lovely Korean lady with nice breasts), Ben Whishaw (the sexy slight thing who plays Keats in Bright Star), Halle Berry, Hugh Grant, Susan Sarandon and the aforementioned Hanks (HANKS)—play up to five different characters in the movie, you never think like, “Oh god, here comes Halle Berry again, only this time wearing a different outfit.”

More so, you’re like, “Is that Halle Berry, or a weird transgendered woman wearing a blonde wig and a dress from Downton Abbey?”

And more than once when you see a male wearing elaborate face make-up, you’re like, “Wait, is Keanu Reeves in this?”

Because like the book, the connections made between each story are tenuous, suggestive, rather than obvious and clean.

The ending gets a little silly. It’s kind of like The Lord Of The Rings, when everything gets wrapped up pretty neatly, and you end up feeling warm and fuzzy, but also irritated. I cried. That’s ok. I actually sobbed. That’s ok too. Both Caleb and I left feeling like it wasn’t the greatest movie we had ever seen, but at the same time, feeling very entertained. It was worth the Hurricane Sandy special price of $7 we paid for it. It would have been worth the full price as well.

Because the more I think about it, the more I realize that I love it, especially the scenes set in the future.

If you have some time to kill this weekend, or some reason to get lost, I’d recommend you’d go see it. The book? Most of you will hate it, and can I read? I don’t know. I’m going to go eat a pop tart and watch Sons of Anarchy.