I’ve always thought clothing should be written about like food, rather than technical equipment – less stitch count, more mouthfeel. A few weeks ago, I was having drinks with a friend, who was telling me about a dinner he had at a local Michelin star restaurant. A multi-course meal there runs $750 per person. Or in his case, $1,500 for him and his wife. On the menu? Avocado toast, supposedly the reason why Millennials can’t afford to buy homes (OK, maybe true here).

“So, how was the toast?,” I asked. My friend shrugged. “Pretty damn good – the best I’ve had. But, you know, it’s avocado toast.”

That’s about the best I can come up with for Marol’s new collaborative shirts with Bruce Boyer, which cost a dizzying $585. Marol is an old, Italian shirt factory based on Bologna, having started in the late 1950s. Recently, the company was sold to new owners, as the current owners don’t have someone in the family for succession (as would be typical in Italian businesses). For much of their history, Marol made their way by producing private-label, finely tailored shirts for top-end companies. Under their new management, however, they’re starting to branch out and develop their own brand.

Many factories have started doing this in recent years – Drake’s, Private White VC, and Simpson, among others. The reasons are often varied, but tied together by the same theme. As the cost of manufacturing has risen in advanced industrial economies – with increased wages and rents – factories have seen manufacturing contracts fly offshore. Plus, for those who produce for fashion labels, there’s often a need to smooth out the production calendar. Fashion works for on a two-season system, which means there are high peaks and low valleys in terms of their work schedule. Having an in-house label allows you to be your own best champion, taking your products directly to consumers. And, more importantly, keep working.

Bo Yang, a commodities trader who now co-owns Marol, knows branding a shirt company is an uphill battle. For one, a shirt is often covered up by a jacket, sometimes even a tie, so it’s rarely seen. Second, many men, including me, think of shirts as being somewhat disposable items. If you accidentally drop a meatball or eat too much pasta, even the best-made button-up is done for. For those reasons, there’s a low ceiling for what many are willing to pay for a shirt.

Yang, however, thinks you can brand a shirt company. Obviously, you need a good product – something that’s well designed, properly cut, and produced to the best standards (“at least according to your philosophy,” says Yang). It also helps to have a rich company history, such as Marol’s, and some stylistic signatures. For Marol, that means a cleaner, sharper Italian shirt than what you might find made in Naples. Whereas Neapolitan shirtmakers revel hand-executed details – often for the sake of them – Marol only includes handwork when they lend something. Yang says:

The buttonholes and armholes are hand-sewn on the Town shirts. Only the armholes are hand-sewn on the country shirts. In general, we are against hand-sewn buttonholes on coarser fabrics (e.g. flannels, tattersalls, denim, and oxfords) as the fibers around the buttonholes are more prone to breaking. It’s less sexy, but we prefer the shirts to last. It’s part of our philosophy to take whatever steps necessary to produce a superior shirt.

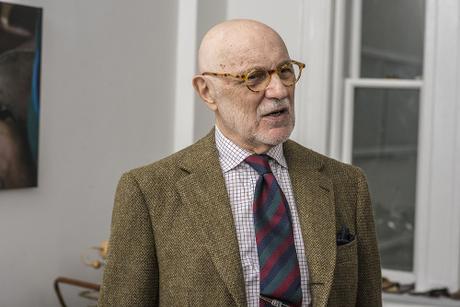

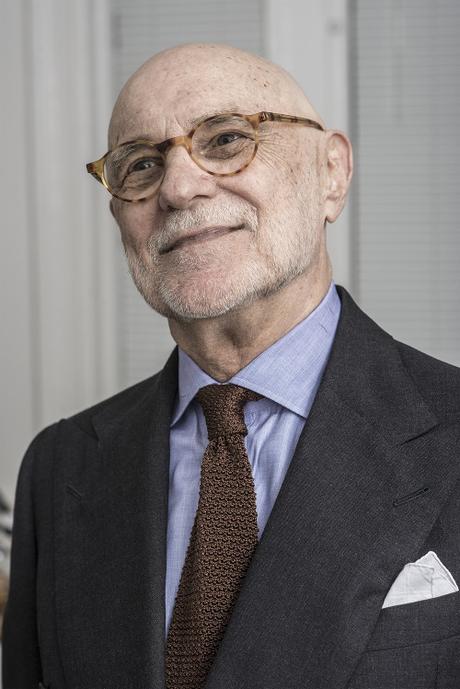

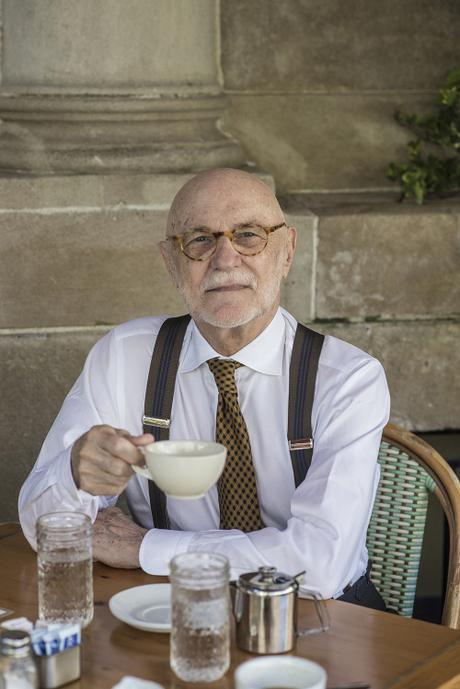

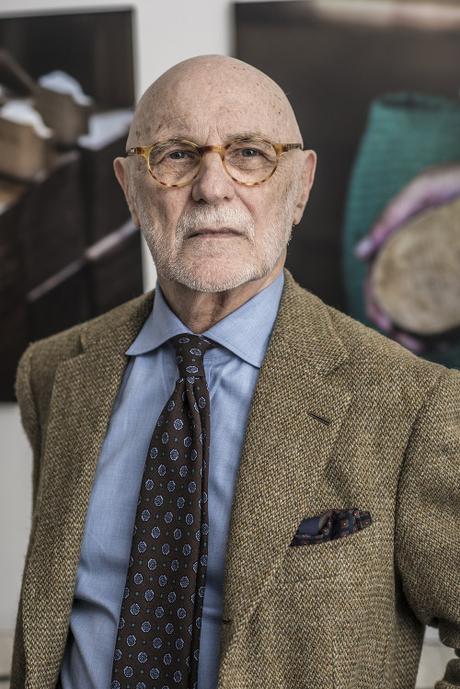

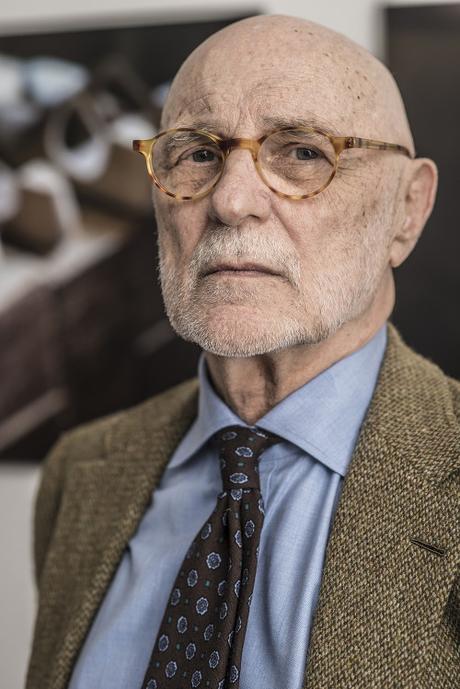

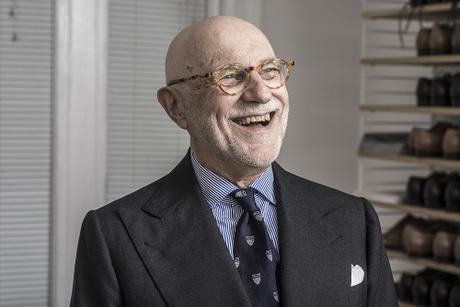

It also helps to have a few high-profile collaborations, such as this one they recently did with Bruce Boyer. “They produce what I think of as a detail-oriented garment,” says Bruce. “They want to get all of the details perfect, down to the smallest fraction of an inch, and everything is thought through with an eye for both utility and elegance. Some people think that you design the garment and then add the details, but the reality is that the details aren’t a gimmick, they are the design.”

Some of Marol’s shirts can be a bit flamboyant, however, with their bold prints and unusual collar styles (many of which are drawn from their archive). Bruce wanted something a bit more sedate, conservative, and traditional. Something for the person “who simply wants to look well dressed without a lot of fuss and bother.” So, he worked with Marol on a small collection of designs that stylistically sit in the middle of the road:

I wanted to make sure the body was neither too billowy nor too tight, just a moderately trim fit with a comfortably high armhole. The collar is a medium spread (nothing drastic like the cutaway) with a balanced height to both the front and back. With the cuffs, I wanted the single button – simplicity really is a virtue, why have three buttons on a shirt cuff? – set back to better accommodate the wristwatch. And I don’t like fancy cuffs either, cuffs with weird shapes; the cuff on this shirt is gently rounded for a perfectly clean look. It’s a simple gentleman’s shirt, but that’s always the hardest thing to find, isn’t it?

I really like how the shirts look on Bruce. They’re tasteful and classic, without any of the overly fancy collars, buttons, and shirt fabrics that I think sometimes detract from a coat-and-tie ensemble. And, like Bruce, I favor sturdy, workhorse fabrics, such as those used for this collection, over the silky stuff you might see on super-lux button-ups.

The only problem is the price. Again, Marol’s entry-level shirts are already painfully expensive at 300 euros, and they’re even more so for this Boyer collection. When I pressed Yang about it, he referred back to their construction. The seams are neatly and finely sewn; the patterns perfectly matched; the little house-shaped gusset is deliberately designed. But this is also the sort of thing you hear from every high-end shirtmaker. I can’t tell you how many tailors over the years have given me the same exact lines. It’s like a sartoria version of that scene from Spinal Tap. “‘How much more fine can this seam be sewn?’ and the answer is 'None. None more fine.”

The best answer I heard came from one of their customers, Andy (pictured above), who’s a friend and reader of this site. He owns a few of Marol’s shirt in their one-piece holiday collars. The collars stand up beautifully, even when worn open, which is rare since non-button-downs often collapse and slip under a jacket’s lapels. In Italy, this style is known as doppio uso, Italian for “double use,” given how it can be worn on- and off-duty.

Andy, who’s used several bespoke shirtmakers, admits there’s no rationalizing the price. “I can get I can get three shirts from Hemrajani for the price of one Marol. Or two from Budd,” he says. “I find Marol’s price to be commensurate with the quality – there is a lot of handwork and the shirts are beautifully made – but it’s more about how the shirt looks. I’ve gotten one-piece collar shirts from other makers and Marol’s are just better, visually. I’m not entirely sure why, but they are. Same with their pique long-sleeved polo. So I get my everyday shirts from those makers. And when I want to look like an Italian movie star, I wear a Marol.”

It reminded me of a problem a friend of mine has when he interviews chefs. All of them give the same answers for why a dish is expensive, and the answers are generic and not terribly helpful. The ingredients are always fresh and locally sourced; the dishes are always cooked with love and attention. The most anyone can say in the end is whether something tastes good.

For those interested in the new Bruce Boyer collaboration, the shirts will be available this fall at select stores, including BRIO in Beijing. US customers can also contact Marol directly for pre-orders. The shirts are $585 a piece. That’s the landed price, with shipping and taxes, and the company allows for returns. Frankly, like Michelin-rated avocado toast, these are too expensive for me. But they do look good.