[CORRECTION: An unfinished version of this post was released earlier today. This post is meant to replace that erroneous post. My apologies for any confusion or in box clutter.]

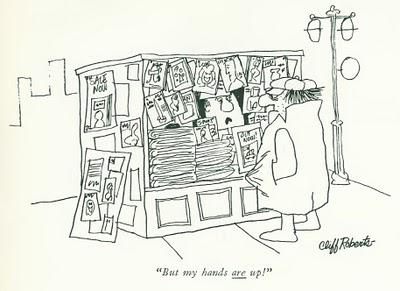

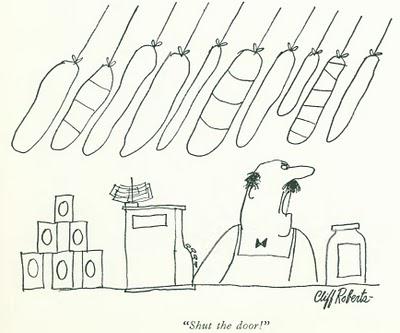

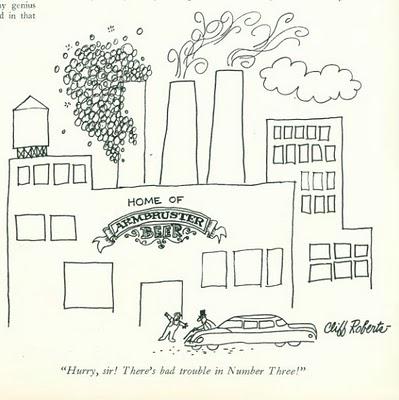

YOU MAY NEVER HAVE HEARD OF CLIFF ROBERTS, but it's likely you have seen his work. He did animations for Sesame Street (Jasper and Julius and Christopher Clumsy are his characters), The Electric Company, and 3-2-1 Contact. He worked on The Smurfs, Shirt Tales, The Pink Panther, and the animated Punky Brewster. He published comics in The New Yorker (see above and below) and in Playboy. He had two syndicated newspaper comic strips, one of which was the short-lived Sesame Street comic. In the legendary animator Gene Deitch's words, Cliff Roberts was "a genius."

Roberts (1929-1999) began his professional career at a Detroit advertising firm while still in his teens. He soon became a frequent contributor to Ford Times, the magazine for Ford drivers, and then in 1949 he was hired by Gene Deitch to do design work for an industrial cartoon. Gene Deitch remembers him in his online memoir:

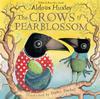

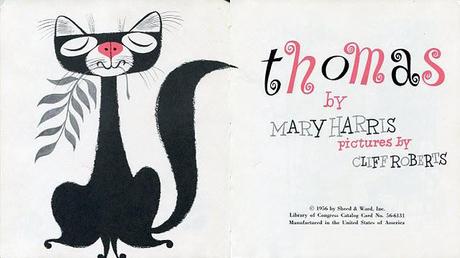

"I would say that my biggest success in the two years I spent working in Motown was my discovery there of two young geniuses, Cliff Roberts and Fred Crippen. Cliff was a rolypoly, gag-spouting jazz fan who showed up at our weekly record sessions...He loved to bang on things to the rhythm of our jazz records, as did I, and we loved to spend the nights hand-drumming together."Roberts moved to New York City in 1950 to advance his career where he became one of the preeminent cartoon designers of the 1950s. It was in the midst of that success that Roberts illustrated Langston Hughes's The First Book of Jazz. For a jazz fan such as Deitch describes, Roberts was perfectly suited for Hughes's book, and the collaboration was named one of the ten best illustrated children's books of 1955 by The New York Times. Roberts went on to illustrate three more children's books: Thomas (1956) by Mary Harris, The Dot (1960), and The Hole (1962), the latter two written by Roberts.

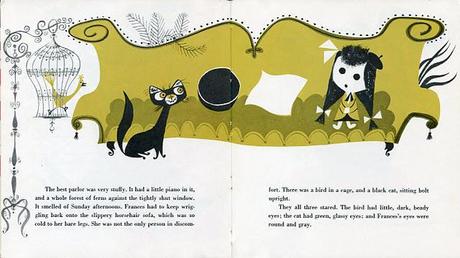

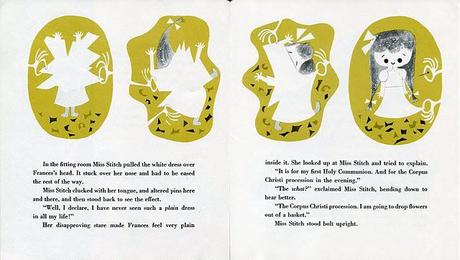

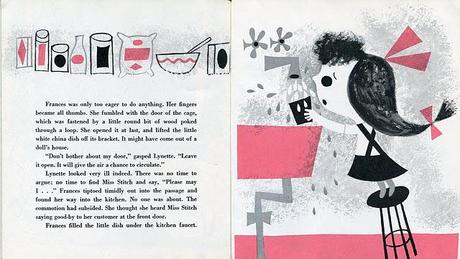

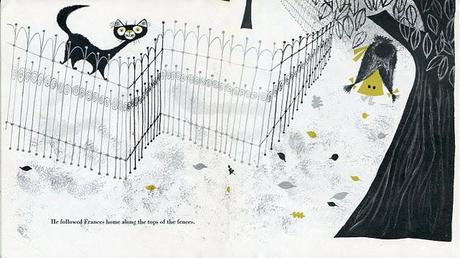

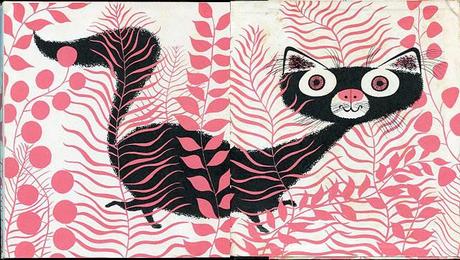

Thomas by Mary Harris is about a cat. Well, really it's about a little girl named Frances who "was to have a white silk dress, quite plain, and reaching to her ankles." The dressmaker is the nasty Miss Stitch who invariably shuttles Frances out to the "best parlor," where she has for her companions a pet linnet named Lynette and the cat Thomas.

These two animals both talk...at least to Frances they talk. She learns that Lynette wants to escape and that Thomas is determined to keep the bird in its place. Both animals hate Miss Stitch.

Over several weeks of fittings and abuse, Frances finds herself alone with Lynette (when one of Miss Stitch's clients faints and Thomas uses the dstraction to escape into Miss Stitch's fitting room in order to create as much havoc as possible). Lynette convinces Frances she is dying of thirst and that the girl must take her water dish and refill it. "'Don't bother about my door...Leave it open. It will give the air a chance to circulate.'"

Of course Lynette escapes. Miss Stitch is surprisingly understanding about it, recognizing that the trouble Thomas has caused in the fitting room is her own fault for letting him in there. At the end of the book, when Frances's mother asks what present she'd like for her first communion (which is what the white dress was for), she asks for Thomas and receives her wish (Miss Stitch thoroughly through with the feline).

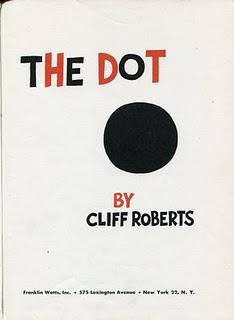

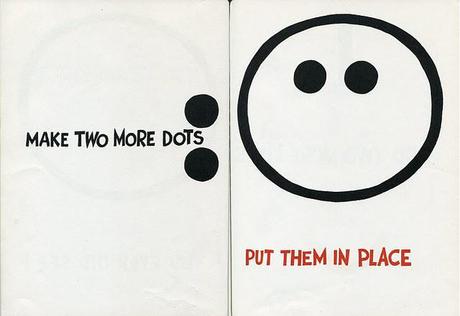

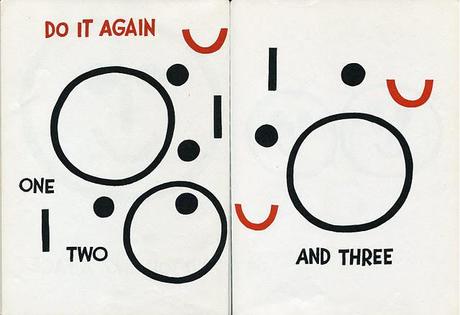

THE DOT BY CLIFF ROBERTS is a message of peace and worldwide brotherhood disguised as a how-to-draw book.

THE DOT BY CLIFF ROBERTS is a message of peace and worldwide brotherhood disguised as a how-to-draw book."This is a dot

Little and fine

Stretch it out

Now it's a line

Bend it a bit

What will it be?

The roundest circle

You ever did see!"

"Add two more lines

And you have a face"

"And now you have a family"The book continues in the same vein adding houses and trees and towns. These same towns are all over the world with families that may look different, but we are all the same, and viewed from a far enough distance what is the whole world but a dot.

The book isn't as graphically flashy as most of Roberts's other work, but the sentiment is certainly in line with someone who would go on to help create Sesame Street.

I MADE AN EFFORT here to focus on the We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie-appropriate and less discussed aspect of Cliff Roberts's career: his work as a children's book illustrator. I have now made available all of the illustrations from three of Roberts's four children's books (as near as I can tell that's all of them). I have uploaded the two books discussed in this post in their entirety. To read the complete books follow the links below to my Flickr sets.

The First Book of Jazz

Thomas

The Dot

If you do want to dive into some of that animation, you can watch many of Roberts's Gene Deitch cartoons online at Cartoon Brew. Several of his Sesame Street cartoons are hosted on the Sesame Street website. Today's Inspiration did a typically fabulous job of spotlighting Roberts, and he's discussed at some length in Cartoon Modern by Amid Amidi. And as mentioned at top, there's Gene Deitch's own autobiography.

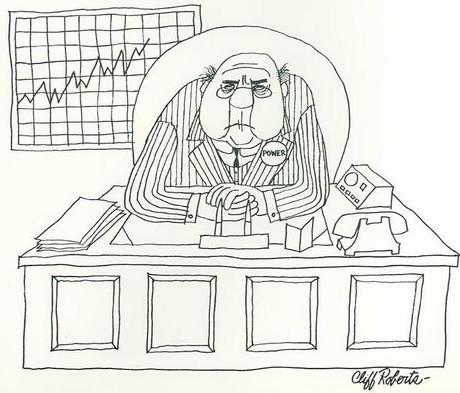

AND NOW, because I had them available to me, here are Roberts's New Yorker cartoons as a bonus.

March 30, 1968

March 30, 1968 June 28, 1969

June 28, 1969  June 20, 1970

June 20, 1970(The New Yorker cartoon at the start of this post is from the August 10, 1968 issue.)

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.