[Cross-posted to By Common Consent]

[Cross-posted to By Common Consent]Despite recent (and ongoing) changes to the Mormon missionary program, the majority of those charged with traveling the world and evangelizing on behalf of the LDS Church are (and will likely remain for a good while yet) young white men from supportive Mormon families in the western United States. Being young, usually not very worldly-wise, usually not very experienced in dealing with foreign cultures or differing sensibilities, and usually carrying around with them expectations shaped by growing up in a family- and tradition-centered church, the Christmas holidays can be a rough time. Twenty-five years ago I was one of them, going through my second Christmas as a Mormon missionary in South Korea. My second Christmas in the country was better than my first. Why? Well, let me explain.

South Korea has more Christians than any other East Asian nation, but that still doesn't make Christmas a major event there, or at least it didn't back in 1988 and 1989. Some stores would put up decorations, and some families would have trees, but overwhelmingly the feeling was that of a borrowed holiday, something that was being embraced (when it was) for reasons that, however deeply felt, weren't at all organic. (Though Christmas is actually a national holiday in South Korea, unlike any other Asian country.) Mormon wards and branches would, like other Christian churches, make mention of the day in talks and songs, but there was little, if any, real cultural spirit behind the celebrations, at least none that I--a 19 and 20-year-old pretentious-and-never-particularly-comfortable white kid from an overdose-on-Christmas upper-middle class family in the western United States (let me tell you about the time Dad brought home an 18ft. pine for our Christmas tree...)--could discern. And I wasn't alone in feeling that way, which at least partially explains the way we American missionaries would go out of our way to create some kind of connection to the holiday (and here I'm speaking overwhelmingly of the elders; the sister missionaries, far more than us males, seemed to be able to integrate into the rhythms of Korean life, perhaps simply because they were such a minority, whereas amongst the male missionaries, Americans dominated).

In December 1988, my first Christmas in the country, that connection was seemingly furnished for us from above. The mission--like the country--was feeling pretty good, I suppose. The Seoul Olympics had been a great success (or at least the Koreans thought so). The country was a year into the presidency of Roh Tae Woo (노태우), and while there were protests aplenty (and would continue to be throughout my time there), the scandals of his presidency hadn't happened yet. (For that matter, neither had the Tiananmen Massacre next door.) Back in those days--at least in our mission--we missionaries had to buy Books of Mormon to sell or give away in our proselyting, and the costs of a Korean mission being pretty high anyway, there was always a grumbling about money, and a great deal of rejoicing when news of some new generous subsidy being bestowed from the mission office, which happened, it must be said, not infrequently. It was in the midst of this that the news came forth: the Korea Seoul West Mission was going to throw a huge mission-wide American-syle Christmas party, at none other location than the 63 Building (육삼 빌딩), which was then the tallest building outside of North America. (As you can see, it kind of dominated Seoul's skyline back then.)

In December 1988, my first Christmas in the country, that connection was seemingly furnished for us from above. The mission--like the country--was feeling pretty good, I suppose. The Seoul Olympics had been a great success (or at least the Koreans thought so). The country was a year into the presidency of Roh Tae Woo (노태우), and while there were protests aplenty (and would continue to be throughout my time there), the scandals of his presidency hadn't happened yet. (For that matter, neither had the Tiananmen Massacre next door.) Back in those days--at least in our mission--we missionaries had to buy Books of Mormon to sell or give away in our proselyting, and the costs of a Korean mission being pretty high anyway, there was always a grumbling about money, and a great deal of rejoicing when news of some new generous subsidy being bestowed from the mission office, which happened, it must be said, not infrequently. It was in the midst of this that the news came forth: the Korea Seoul West Mission was going to throw a huge mission-wide American-syle Christmas party, at none other location than the 63 Building (육삼 빌딩), which was then the tallest building outside of North America. (As you can see, it kind of dominated Seoul's skyline back then.)

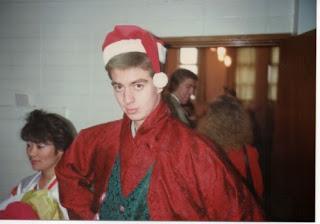

It was a strange couple of days, rest assured. Missionaries gathered from all over; we crashed at each others' apartments, and those elders and sisters who had been around for a while made plans for a mostly unsupervised day in Seoul, while we newbies (I'd only been in the country for a few months by then) listened in, intimidated and scandalized and envious. The party took place in the banquet room, where we were fed not just fine Korean fare, but oysters, fresh roast beef, salmon, and lobster. Missionaries wandered throughout the building, up to the observatory deck, trading war stories and jokes and (no doubt) outright lies. There was a talent show which got completely out of hand, with different groups of elders and sisters competing with each other to win prizes (a competition which got fierce enough that when one group of sisters, decked out in black ninja outfits, took to the stage to perform a rather impressive choreographed dance to some K-Pop hit of the day, another group of American elders rushed on to the stage and promptly broke out in all sorts of--in retrospect, rather pathetic--break dance moves, thus disrupting their act), all of which came to a rousing end with U2's "Desire" blasting over the loudspeakers. (That was the choice of the American zone leader who'd somehow ended up in charge.) Truly, it was a bit crazy. I mean, there was an ice sculpture of the Korean Temple, for heaven's sake. I have no idea how much the whole thing cost (the long-time financial secretary to the mission was released soon afterward and, the rumors flew, sworn to secrecy), but it was a small touch Reagan's bull-market America, right there in Korea. I've often shared stories of this party with other missionaries, and when I think about how outrageous it all was, even I have a hard time believing it happened. Thank goodness I had my camera and, thus, hard evidence.

It was a strange couple of days, rest assured. Missionaries gathered from all over; we crashed at each others' apartments, and those elders and sisters who had been around for a while made plans for a mostly unsupervised day in Seoul, while we newbies (I'd only been in the country for a few months by then) listened in, intimidated and scandalized and envious. The party took place in the banquet room, where we were fed not just fine Korean fare, but oysters, fresh roast beef, salmon, and lobster. Missionaries wandered throughout the building, up to the observatory deck, trading war stories and jokes and (no doubt) outright lies. There was a talent show which got completely out of hand, with different groups of elders and sisters competing with each other to win prizes (a competition which got fierce enough that when one group of sisters, decked out in black ninja outfits, took to the stage to perform a rather impressive choreographed dance to some K-Pop hit of the day, another group of American elders rushed on to the stage and promptly broke out in all sorts of--in retrospect, rather pathetic--break dance moves, thus disrupting their act), all of which came to a rousing end with U2's "Desire" blasting over the loudspeakers. (That was the choice of the American zone leader who'd somehow ended up in charge.) Truly, it was a bit crazy. I mean, there was an ice sculpture of the Korean Temple, for heaven's sake. I have no idea how much the whole thing cost (the long-time financial secretary to the mission was released soon afterward and, the rumors flew, sworn to secrecy), but it was a small touch Reagan's bull-market America, right there in Korea. I've often shared stories of this party with other missionaries, and when I think about how outrageous it all was, even I have a hard time believing it happened. Thank goodness I had my camera and, thus, hard evidence.A week after than party I was transferred to Ansan (안산)--or "Banwol" as some of the older locals who had been shaped by the Japanese occupation more than four decades earlier still referred to it. Today Ansan is part of the greater Seoul megapolis, but a quarter-century ago it was coastal town whose connection to the big city was a single (admittedly busy) train route. There was a small Mormon branch there, which met in an upstairs office space, where we'd huddle around a single coal stove for protection from the cold winds coming off the sea that would pass through the thin walls and windows with ease. It was, for me, a lonely and dispiriting place to spend the holiday, made worse, I suppose, by my constant berating of myself for feeling that way. I found myself listening to my homemade cassette tape recording of the Osmond Christmas album (the original double album, with the solo number by Merrill which never made it on to either of the cd releases) constantly, though the song I most associate with that Christmas was a ridiculously maudlin cover of Wham's "Last Christmas" by Lee Sun Hee (이선희) which I seemed to hear everywhere and which brought me to the brink of tears almost every time. (In the decades since, it has apparently become a bit of a seasonal K-Pop stable, though usually shorn of the aching earnestness of the 80s version.)

There was a genuine attempt to bring some Christmas spirit into our shared drab space that holiday, with a Christmas Eve social during which a group of Primary-aged children sang some songs and a short nativity was acted out. Unfortunately, we American elders decided once again to engage in our usual indefensible antics, and elected, as our contribution to the branch's entertainment, to track down a copy of Run-DMC's "Christmas in Hollis" (I remember traveling solo outside of my assigned district to record a copy of it which was in the possession of another elder), put on blackface, and proceed to act out the song in most predictably insultingly and racist way you can imagine. (Why did we do this? Because we were bored and stupid and young and utterly oblivious to what our own unthinking, self-pitying silliness represented. In our defense: at least we didn't do anything to get ourselves arrested. Also, while it provides no justification whatsoever, it can't be denied that the branch absolutely loved our fake-rap routine; it brought the whole house down.) An embarrasingly entertaining capstone to my first Christmas in Korea when the story is related to others, perhaps, but it did little to change what was a pretty morose holiday for me.

There was a genuine attempt to bring some Christmas spirit into our shared drab space that holiday, with a Christmas Eve social during which a group of Primary-aged children sang some songs and a short nativity was acted out. Unfortunately, we American elders decided once again to engage in our usual indefensible antics, and elected, as our contribution to the branch's entertainment, to track down a copy of Run-DMC's "Christmas in Hollis" (I remember traveling solo outside of my assigned district to record a copy of it which was in the possession of another elder), put on blackface, and proceed to act out the song in most predictably insultingly and racist way you can imagine. (Why did we do this? Because we were bored and stupid and young and utterly oblivious to what our own unthinking, self-pitying silliness represented. In our defense: at least we didn't do anything to get ourselves arrested. Also, while it provides no justification whatsoever, it can't be denied that the branch absolutely loved our fake-rap routine; it brought the whole house down.) An embarrasingly entertaining capstone to my first Christmas in Korea when the story is related to others, perhaps, but it did little to change what was a pretty morose holiday for me.Christmas in 1989 was different, perhaps because I'd matured, and got some of the self-pity and self-aggrandizement (yes, those two emotions can go together) out of my system, or perhaps because the odd go-for-broke sentiment that characterized so much of my first year or so in the mission seemed to have dissipated. I still wasn't at peace with missionary work (that actually wouldn't come until many years after I came home), but I'd been assigned to a large ward in Suwon (수원), where I ended up spending the final year of my mission, something I am profoundly grateful for. There was a feeling of genuine community in that ward, or at least I could feel that the community was there, and draw some strength from that, outsider though I was.

The mission had another Christmas party, though this one was far less extravagant. Talent shows and silliness abounded, as always, but I think this time around there was less pretension, less of a "what can we get away with this time" sensibility, and more honest fun. A bunch of us got together, ostensibly to do a scene from The Pirates of Penzance, but actually singing Ray Stevens's "The Pirate Song," and it was a blast (though, perhaps predictably, given my general shamelessness, I was chosen to play lead, and I have to tragically admit that my sensitivity to the way unintended disrespect for marginalized segments of the population could be expressed through stylized self-mockery hadn't at all improved in a year's time: I went out on that stage, and I was flaming.) Christmas Eve itself was spent at the home of generous, older American Mormon, a man who was a veritable Santa Claus/Father Confessor to lonely and struggling missionaries far from home, on Osan Air Base, Songtan Station, which was near Suwon. I spent much of the evening attempting to explain, in whatever level of ridiculous detail my broken Korean allowed, the plot and significance of "Miracle on 34th Street" (the original, being shown that night on the Armed Forces Korean Network!) to the lone Korean member of our party. The snow fell heavily that night as we took a late bus back to our apartment, and a reflective, simple song "또다시 크리스마스" ("Again Christmas"), from the second (and last, and not as good) album by the 80s K-Pop masters Deul Guk Hwa (들국화) was playing from an intercom outside a store near the bus stop. The brassy, yet humble tune and lyrics ("어디에나 소리 없이 사랑은 내리네"--"Love is falling everywhere without a sound") fit my mood perfectly.

The mission had another Christmas party, though this one was far less extravagant. Talent shows and silliness abounded, as always, but I think this time around there was less pretension, less of a "what can we get away with this time" sensibility, and more honest fun. A bunch of us got together, ostensibly to do a scene from The Pirates of Penzance, but actually singing Ray Stevens's "The Pirate Song," and it was a blast (though, perhaps predictably, given my general shamelessness, I was chosen to play lead, and I have to tragically admit that my sensitivity to the way unintended disrespect for marginalized segments of the population could be expressed through stylized self-mockery hadn't at all improved in a year's time: I went out on that stage, and I was flaming.) Christmas Eve itself was spent at the home of generous, older American Mormon, a man who was a veritable Santa Claus/Father Confessor to lonely and struggling missionaries far from home, on Osan Air Base, Songtan Station, which was near Suwon. I spent much of the evening attempting to explain, in whatever level of ridiculous detail my broken Korean allowed, the plot and significance of "Miracle on 34th Street" (the original, being shown that night on the Armed Forces Korean Network!) to the lone Korean member of our party. The snow fell heavily that night as we took a late bus back to our apartment, and a reflective, simple song "또다시 크리스마스" ("Again Christmas"), from the second (and last, and not as good) album by the 80s K-Pop masters Deul Guk Hwa (들국화) was playing from an intercom outside a store near the bus stop. The brassy, yet humble tune and lyrics ("어디에나 소리 없이 사랑은 내리네"--"Love is falling everywhere without a sound") fit my mood perfectly.

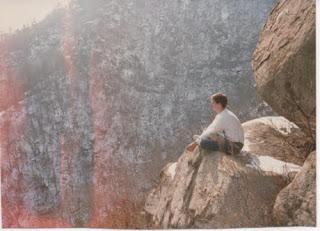

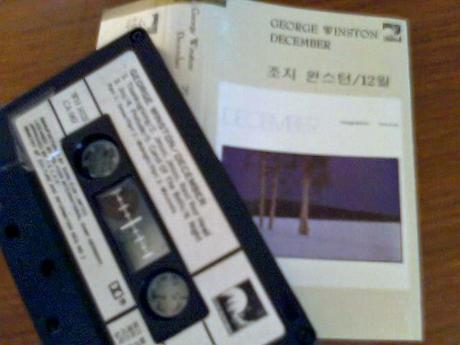

My favorite memory from that holiday season, 1989, was traveling with a large number of young people from our ward far outside out proselyting area--outside our mission boundaries, in fact, though I suspect no one remembered to inform the mission leadership, thank goodness--to climb Mt. Soyo (소요산), north of the city of Seoul. It was a huge event, planned for weeks and involving close to 30 people. It was bitterly cold day, enough to make one want to bail on the 4am start time, but in the end it was a trip filled with camaraderie and good humor. We packed in our meals and had a glorious cookout in near-freezing temperatures. We explored Buddhist shrines and talked about religion and nature and fate. We challenged each other--missionaries and Korean members alike--to rock climbing contests and snow ball fights. We missionaries swapped stories, sure, but I thought there was a little more openness, a little more receptivity, in what I heard--at least, I hope there was more of than in what came out of my mouth. We made it all the way to peak, and--as was (and I hope still is) typical of the Korean people--we sang songs and gave each one of ourselves a little bit of alone time. I had my Walkman with me, and a tape that I'd picked up at a music shop somewhere in Suwon, a tape which I still have today: a Korean production (hopefully legally obtained, but quite possibly not) of George Winston's December. I can remember sitting near the top of the mountain, listening to his rendition of "Jesus, Jesus Rest Your Head" three or four times over. (Obviously, much of my pretension remained, but still: it was a wonderful moment, one which impressed upon me a sense of quiet majesty and grace and simplicity which I found beautiful. However much growing and maturing my mind and soul still needed and still had awaiting them in the months to come, that Christmas moment was one worth treasuring.)

My favorite memory from that holiday season, 1989, was traveling with a large number of young people from our ward far outside out proselyting area--outside our mission boundaries, in fact, though I suspect no one remembered to inform the mission leadership, thank goodness--to climb Mt. Soyo (소요산), north of the city of Seoul. It was a huge event, planned for weeks and involving close to 30 people. It was bitterly cold day, enough to make one want to bail on the 4am start time, but in the end it was a trip filled with camaraderie and good humor. We packed in our meals and had a glorious cookout in near-freezing temperatures. We explored Buddhist shrines and talked about religion and nature and fate. We challenged each other--missionaries and Korean members alike--to rock climbing contests and snow ball fights. We missionaries swapped stories, sure, but I thought there was a little more openness, a little more receptivity, in what I heard--at least, I hope there was more of than in what came out of my mouth. We made it all the way to peak, and--as was (and I hope still is) typical of the Korean people--we sang songs and gave each one of ourselves a little bit of alone time. I had my Walkman with me, and a tape that I'd picked up at a music shop somewhere in Suwon, a tape which I still have today: a Korean production (hopefully legally obtained, but quite possibly not) of George Winston's December. I can remember sitting near the top of the mountain, listening to his rendition of "Jesus, Jesus Rest Your Head" three or four times over. (Obviously, much of my pretension remained, but still: it was a wonderful moment, one which impressed upon me a sense of quiet majesty and grace and simplicity which I found beautiful. However much growing and maturing my mind and soul still needed and still had awaiting them in the months to come, that Christmas moment was one worth treasuring.)I've not saved my missionary journal, not any of the letters I sent or received from my 22 months in South Korea. That's a loss, I recognize, especially when it comes to writing down memories like these: there's so much that I need to reconstruct, so many disconnected pieces of evidence--a photograph here, an odd note there--that's it hard to avoid accepting that I might have all sorts of essentials wrong, or might be including the accidental inventions of two decades' worth of oral story-telling in my account. But then honestly, just how distant is anyone's memory from myth? I'd love to return to South Korea someday, and travel back to Ansan, and Suwon, and Mr. Soyo, and Osan Air Base, and see if there was anything I remembered, anything I could connect with. Maybe there would be; I'd love to believe that all the good things--the language, the friendships, the positive lessons--would come flooding back. But maybe they wouldn't. And in which case...well, isn't that what invented memorializations like holidays (like everything we manufacture and make our own, again and again, out of our own subjective acts of cultural retrieval and interpretation) are for? So that we can reconnect with ourselves, set apart and see those moments of foolishness and joy and despair and grace for what they are. I had many such moments in Korea. Some, clearly, were better than others. But still, this Christmas, I'm grateful for them all.