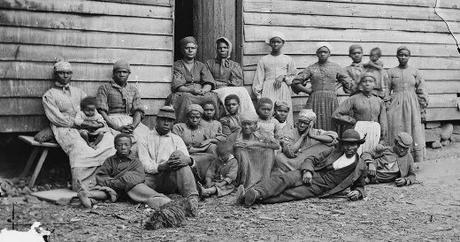

Image from http://www.thepeoplesview.net

With Easter finally having arrived, a renewal of life and good weather has finally arrived. Just as Jesus Christ rose from the dead, the flowers are now in bloom, the barren trees have sprouted new leaves and the warmth of the sun pounds the ground below from the sky. During Spring, we all give thanks to Nature and God for a new year, one that always seems better than the dreary, darkened winter days that preceded it. However, as we all celebrate the wonders and mercy of the Lord (or whatever deity one chooses to believe), it is important to reflect on a period of American history when religion wasn’t just about faith and spiritual redemption, but also freedom and liberty in a prejudiced and racially charged country.

The Africans who came to the Americas as slaves were not initially Christian; roughly 20% were Muslim, and a majority practiced various forms of animism. Once they arrived, their white owners indoctrinated them into their Christian traditions: The United States tried to convert them into various forms of Protestantism and the French, Spanish and Portuguese colonies in Haiti, Dominican Republic, and South America forced Catholicism on their slave populace.

Through from a twenty-first century lens that has not studied the racial make-up and history of this nation, it would be natural to believe that the slave owners simply wanted their new slave population to be brought up on the righteous pat of Christianity. Sadly, this was not the case; though whites believed in their faith, they did not necessarily believe that African-Americans should benefit from the same religious teachings. The main cause for the widespread attempt at Christian conversion for blacks in the United States was in order to eliminate the cultural and spiritual heritage that African-Americans brought to the United States as well as control their slave populace more effectively.

During the 1700s, many slaves were forced to go with their white owners to Christian churches which taught that obedience to whites would allow blacks to reach spiritual salvation in the church. Teachings such as this not only created Uncle Toms, but also lowered the self-esteem, dignity and respect of African-Americans across the country. Had the slave owners been successful, an entire subgroup of the population would have lost their cultural identity and have been recreated as servile, non-humans who had no hope for freedom. On the contrary, the whites at the time didn’t know that the church would actually strengthen the blacks’ resolve to win their independence and maintain their cultural heritage.

Utilizing elements of animism and musical rhythms and styles that their grandparents brought form across Africa, blacks managed to recreate Christianity in their own image. Religions such as Haitian Voodoo, Cuban Santeria began forming in the Caribbean, each using African music and drums during their masses and ceremonies. In the United States, for examples, Baptists and Methodists made gospel music from the Delta blues. These forms of religious expression were heavily persecuted by whites during the late 1700s, and many African-Americans were forced to practice their faith in hiding. Once slavery was abolished, however, black churches started springing up across the United States, especially in the North where there was a larger concentration of free blacks. As these practices spread, the culture and ceremonies associated with them spread, creating the beginnings of a unique African-American religious experience that still exists today in predominantly black churches.

However, these church meetings were not simply places for worship; often, these churches (which were mostly small shacks in the early-mid 1800s) served as a meeting place for African-Americans to organize and plan revolts. The most famous slave revolt was led by Nat Turner, a Christian preacher who led the largest slave rebellion in the American South at the time, in 1831. It is no wonder why men like Nat Turner were considered prophets; they fought for the freedom of their fellow brethren, just as Christ had preached two millennia ago.

For Christians today, their religion is way of life, a path to righteousness and eventual spiritual salvation at the end of days. For African-Americans, however, Christianity is not a faith whose only purpose is to assist them in the afterlife. Instead, they consider themselves somewhat akin to Jesus himself: a man who lifed true and virtuously, yet suffered at the hands of injustice and prejudice. His resurrection led him not into the same darkness which had killed him, but into the light of the Father, into a land without hatred, greed, and violence. As followers of Christ, we anticipate our transcendence into Heaven above; as African-Americans, we use Jesus’ story as an inspiration for all our brethren facing persecution and injustice in the name of hatred and racism, striving towards equality and liberty today so future blacks do not have to suffer like our forefathers did. What the history of African-American Christianity teaches us today is that, regardless of belief, faith plays a great role in supporting the downtrodden and outcasts of society, giving hope to the hopeless, a voice to the mute, and gives excellent examples that teach men how to live well, whether poor or affluent, both in this lifetime and the afterlife.