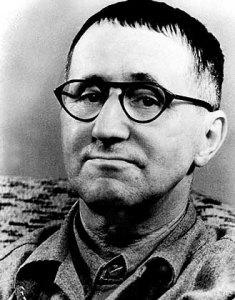

Playwright Bertolt Brecht (aphorism4all.com)

The significance of Bertolt Brecht’s groundbreaking theories from the twenties and thirties on the burgeoning Brazilian theater of the mid-fifties to late sixties cannot be overstated. Indeed, his works have had a lengthy history and influence in the land of samba long before Chico ever wrote a note of the song form.

As well, his dynamic views on the art and substance of the theater have spread across most fields of human endeavor, beginning of course with the European stage. As one of the acknowledged architects of “epic theater,” Brecht’s revolutionary ideas about his craft — put into worldwide practice upon his early death in 1956 — revolved around, among other things, the complete destruction of all pretense and illusion.

For starters, both actors and stagehands, along with members of the orchestra, played his pieces in full view of the audience; no curtain was discernible as such; the houselights were invariably kept on, not dimmed; the proscenium arch no longer provided an imaginary divide between artist and public; signs and placards were displayed to announce the beginning and ending of scenes; exhortation was encouraged outright for those sitting in attendance; and there were other innovations at play as well, many of which we take for granted today.

Suffice it to say, then, that what Herr Brecht hoped to achieve by this more didactic approach to theater was a certain distancing (or “alienation,” if you will) of the spectators by those directly involved with the play’s production.

Theoretically, this distancing effect would prevent viewers from becoming overly bound-up in the drama they were witnessing. Moreover, by precluding any real attachment to the onstage action, the main message of the piece would reveal itself with facility and ease, thus the end result would be a play that could be judged “objectively and with intelligence,” and on its own terms, independent of the performance in question.

In sum, reason, not the emotions, would be properly engaged, and (again, in theory) understanding would ultimately prevail.

But the real thrust behind Brecht’s formal arguments was a call for social justice and change through heightened political awareness. (Not for nothing was he known as a lifelong follower of Karl Marx.) Although some of the more conservative elements in Germany thought he had gone well beyond the normal conventions of the times, Brecht nonetheless held fast to his belief that a better-informed lower class could conceivably expect — no, demand — some improvement (or “transformation”) in their lives by the complacent upper crust.

If all this sounds vaguely familiar, it was because the German playwright’s practical dialectic found equal favor with, and rang remarkably true for, most socially conscious dramatists of the day, particularly the downtrodden masses of Brazilian artists longing to break free of the military’s suffocating grasp.

Among the early proponents of Brecht’s far-reaching techniques were some of the country’s most progressive stage figures, including Oduvaldo Vianna Filho, with Centro Popular de Cultura and Grupo Opinião; José Celso (“Zé Celso”) Martinez Corrêa, and the Teatro Oficina; Millôr Fernandes and Flávio Rangel, and their play Liberdade, liberdade (“Freedom, freedom”); the writings of Dias Gomes (O berço do heroi – “The Hero’s Cradle”); and the still relevant work of the late Augusto Boal, with the Arena Theater and, most radical of all, his Teatro do Oprimido (“Theater of the Oppressed”) and the huge debt it owed to Brecht — the direct benefit of which was Boal’s own studies into empowerment of the people by means of finding and expressing their individual voices through carefully worked-out activities and routines (“forum theater,” “cop-in-the-head,” “rainbow of desire,” et al.).

To this list must also be added Brecht’s unofficial “offspring,” those contemporary, cutting-edge directors — Antunes Filho, Ulisses Cruz, Moacir Góes and Gerald Thomas — who have contributed mightily to the exploration of what is feasible on the Brazilian stage, and succeeded (for the most part) in reshaping the building blocks of postmodern theater into new and untried forms.

Filmmaker Glauber Rocha (rdeminas.tv)

But it did not stop there, as the approaching “new wave” of the Cinema Novo movement (“a cinema of the humble and the offended”) — another of the popular Brazilian art forms to have profited from the Brechtian ideal — seemed to have projected.

Such award-winning filmmakers as Nelson Pereira dos Santos (Rio zona norte, 1957; Vidas secas – “Barren Lives,” 1963), Ruy Guerra (Os fuzis – “The Guns,” 1964), and Glauber Rocha (Barravento, 1962; Deus e o diabo na terra do sol – “Black God, White Devil,” 1964; Terra em transe – “Land in Anguish,” 1967; Antonio das Mortes, 1969), along with Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, Carlos “Cacá” Diegues and Roberto Santos, were just a few of the domestic auteurs active during this period, the most politicized of which was the Bahian-born Glauber, whose classic 1965 essay, “An Aesthetic of Hunger” — a Marxist manifesto (“Violence is normal behavior for the starving”) if ever there was one — is required reading for any lover of neo-realist cinema.

Not to be discounted, of course, was the somewhat spotty revival in Brazil of the rich Brecht-Weill repertory of cabaret standards, first undertaken by Grupo Orintorrinco, and featuring Maria Alice Vergueiro (who sang in the 1978 premiere of Ópera do Malandro) as soloist; then with the 1988 release of Cida Moreira’s album (in Portuguese) of Cida Moreira Interpreta Brecht; followed a decade later by the CD Concerto Cabaré with nightclub staple Suzana Salles, a native paulistana perfectly at home not only with the Teutonic language and style (“Her interpretations transcend the Brazilian milieu,” raved music critic Daniella Thompson), but in Brecht’s home city of Berlin, where she had studied during the 1980s.

(End of Part Three)

Copyright © 2012 by Josmar F. Lopes