Here's another set of excerpts I'd like to share with you from Charles Marsh's excellent biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (NY: Knopf, 2014). Marsh ruffled feathers of conservative Christians (and the ruffling goes on and has become even more agitated with Diane Reynolds' 2016 Bonhoeffer biography The Doubled Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Women, Sexuality, and Nazi Germany) by concluding that Bonhoeffer was a gay man deeply in love with fellow Lutheran pastor Eberhard Bethge.

In Marsh's view, the evidence suggests that this relationship was likely not consummated and that Bethge did not reciprocate Bonhoeffer's passion to a degree that satisfied Bonhoeffer. When Bethge announced his engagement to Bonhoeffer's niece Renate Schleicher in 1942 (Bethge was thirty-four and Schleicher eighteen at the time), Bonhoeffer responded by engaging himself to Maria von Wedemeyer, seventeen years his junior and the first girlfriend he had ever had. To say that Bethge's announcement of his intent to marry Renate Schleicher unsettled Bonhoeffer would be an understatement: it led to an impulsive decision far out of character for Bonhoeffer, which is now the slim straw on which conservative Christian commentators troubled at the thought that this Christian martyr-theologian was — as I think Marsh shows very convincingly — a gay man deeply in love with another man want to build their heterosexual hopes for Bonhoeffer.

An interesting theme running through Marsh's biography, which is not ever made completely explicit (though see the passage at the head of this posting), is that Bonhoeffer's extraordinary sensitivity to other religious traditions and to those on the margins of society — the openness his theology and especially his christology displays to the Other — has much to do with his homosexuality.

On a trip he made with his brother to Rome when both were young men, Bonhoeffer found himself deeply drawn to the drama of Catholic liturgy — an attraction that continued when he pastored a Lutheran church in Spain after he was ordained. He had little of the polemical stance of Luther when it came to interaction with Catholics, and in the period he spent at the Benedictine abbey in Bavaria, Ettal, as he wrote his Ethics while engaging in underground work on behalf of the Resistance, he enjoyed a strongly cordial relationship with the abbot of the monastery and many of the monks there.

In the time he spent at Union Seminary in New York in 1930, Bonhoeffer found himself drawn with equally strong attraction to the African-American church — an expression of Christianity totally new to him, which revolutionized his thinking about the Christian gospel and the Christian church. Bonhoeffer found white American Christianity anemic and cold — unserious and theologically shallow in the extreme. He found the black church very much the opposite of all of that. As Marsh writes,

He also notes that when Bonhoeffer returned to Germany and began his ministry in the Confessing Church as the Nazis consolidated their power, he mediated African-American spirituality and theological ideas to the Christian Resistance movement in Germany:

By the mid-1930s, singing the Negro spirituals and listening to recordings of them would become a vital part of the dissident circles in Germany that gathered around Bonhoeffer (pp. 118-9).

When Bonhoeffer read Barth's Word of God and Word of Man and encountered Barth's insistence that "we must take the trouble to go off far enough to hear the Word again," he responded as follows, Marsh suggests:

Bonhoeffer now knew himself able to go that distance, for, as he said, "I heard the gospel preached in the Negro churches" (p. 134).

His transformative encounter with the black church in his time in New York led Bonhoeffer to one of the central insistences of his theology:

No longer would he speak of grace as a transcendent idea but as a divine verdict requiring obedience and action. The American social theology, which had seemed so devoid of miracle, had remade him into a theologian of the concrete (p. 135).

Marsh summarizes the transformation American social theology, especially as manifested in the black church experience, had on Bonhoeffer's thought as follows:

In America, Bonhoeffer had found the presence of Christ most palpable among those on the margins. In the Christology lectures Bonhoeffer delivered in 1933 in Berlin, he began to speak of "the outcast Christ" and "the Christological incognito" — a direct response to the Nazification of the church and the rise of Hitler with his attack on the Jews (p. 172).

Now for a series of excerpts from Marsh's book dealing directly with Bonhoeffer's relationship to Bethge (most of these are screenshots from Strange Glory at the Google books site; the darker ones are photos I've taken of pages in the book itself, which were not scanned by the copy at Google books):

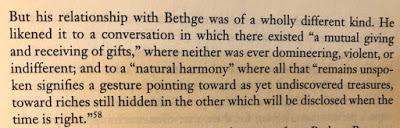

Bonhoeffer's relationship with Bethge began in the fall of 1935 when Bethge was Bonhoeffer's student at the Finkenwalde seminary-cum-religious-community Bonhoeffer and other Confessing Church leaders set up to bolster the Confessing Church and its resistance to the Nazis. Marsh speaks here of that budding period of the two men's relationship:

As the relationship unfolded, in 1936, Bonhoeffer ended an epistolary friendship he had with his cousin Elizabeth Zinn, whom some biographers have suggested Bonhoeffer intended to marry:

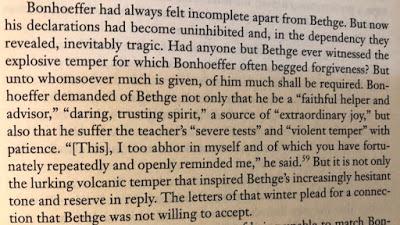

It was in the winter of 1940 and early 1941 that Bonhoeffer spent time at Ettal Abbey writing his Ethics, enjoying the hospitality of the Benedictine monks, and engaging in undercover activities to try to topple Hitler: his relationship with Bethge continued to be of paramount importance. Marsh speaks of this period of Bonhoeffer's life in these passages:

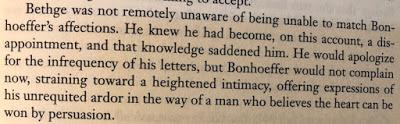

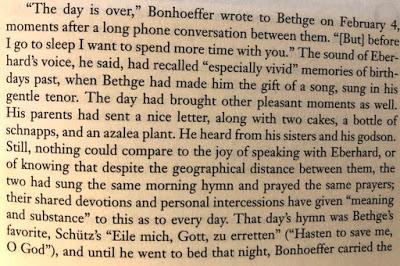

The following passages refer to early 1941, as Bonhoeffer continued at Ettal:

Then came Bethge's announcement of his engagement to Bonhoeffer's niece Renate and Bonhoeffer's rejoinder — his pursuit of and engagement to Maria von Wedemeyer — which Marsh discusses as follows, with what seems to me insightful, sensitive understanding of the dynamics at play in this part of Bonhoeffer's life:

The strange need of conservative Christians to twist these biographical details about Bonhoeffer's engagement to Maria von Wedemeyer into a narrative about his heterosexuality — when it's very clear that his homoerotic love for Bethge was a central pillar of his life — is puzzling, isn't it? What is so threatening about the thought that a major theologian-martyr of the twentieth century was, as is plain, a gay man?

What is so threatening about the thought that some people are made queer, that they have minds and hearts that can love God and other people every bit as much as heterosexual people can do? Marsh is a heteerosexually married man with children, by the way. I have not yet read Reynolds' book but intend to do so.

If I seem to be belaboring these aspects of Marsh's biography, it's because resistance to the thought that any leading Christian figure might have been gay or lesbian remains exceptionally strong in some sectors of Christianity today, and the attempt to hide, deny, lie about the homosexuality of important theologians, saints, writers, artists, philosophers, scientists — you name it — is still very much alive and well in the world in which we live today.

It needs to be resisted.